News that two of the United States’ most famous racetracks, Santa Anita Park in California and Gulfstream Park in Florida, are being examined for sale marks the latest chapter in racing’s complex relationship with urbanisation.

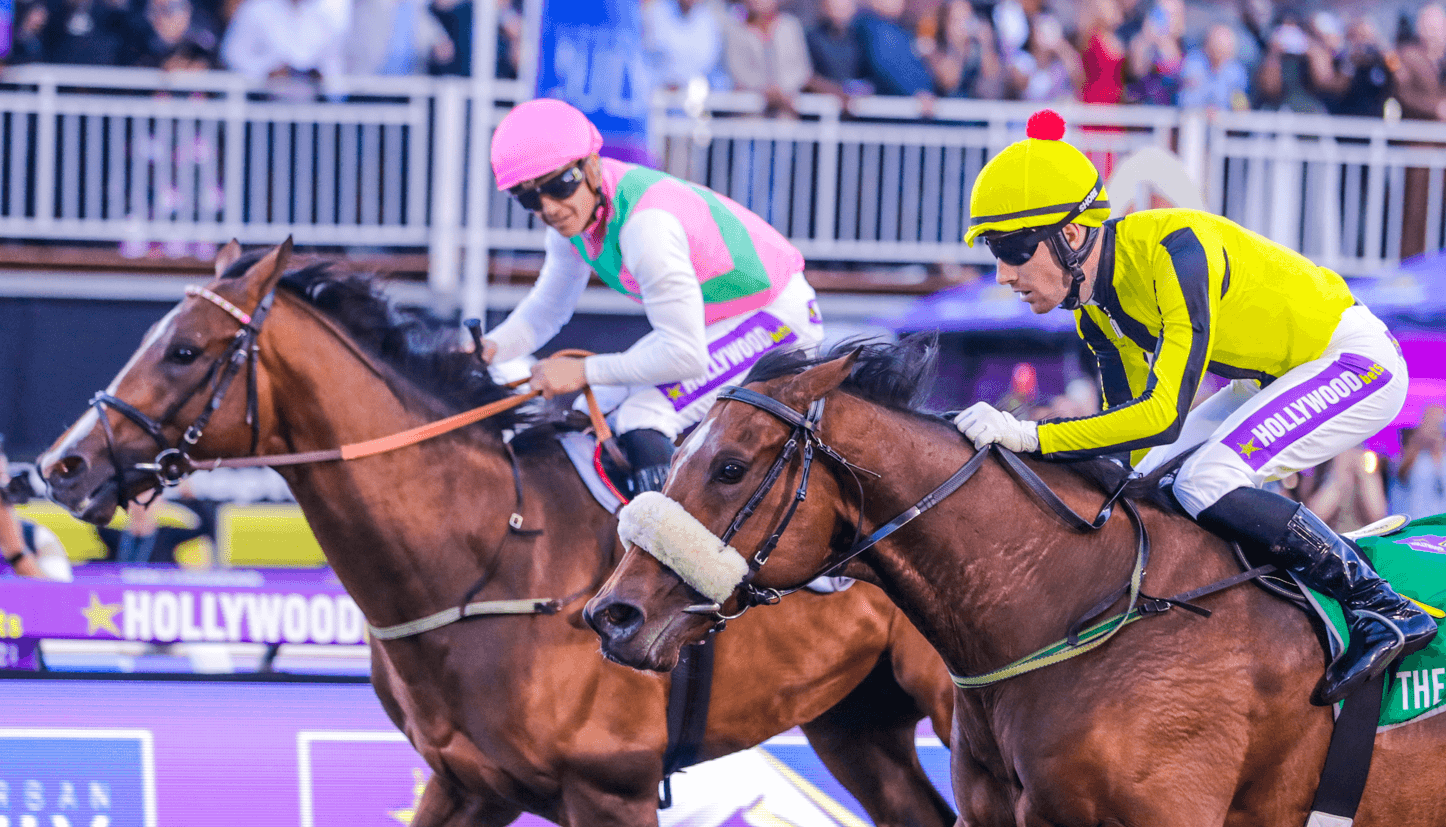

It was reported earlier this week that Stronach Group, which owns both courses under its 1/ST Racing banner, had re-hired former executive Keith Brackpool to explore the sale of their racing portfolio. It followed an interview that the company’s chief Belinda Stronach gave on NBC before the running of one of Gulfstream’s flagship races, the Pegasus World Cup, last month.

“The fact is Gulfstream Park is now in a very dense, urban setting and that’s not great for horses, ultimately,” Stronach said. “Let’s continue to have discussions about what is in the best interests of the horses. We don’t need to be in a dense, urban setting. We need a long-term plan.”

While there is no indication that racing could cease imminently at the historic Santa Anita Park in Arcadia, north of Los Angeles, Stronach’s interview is the latest sign that the sport is on borrowed time at Gulfstream Park in Fort Lauderdale.

Stronach Group executives have told horsemen that they will guarantee racing at the site through 2028, but only if a controversial ‘decoupling’ bill passes through the Florida legislature.

The bill – which advanced to the House of Representatives by a comfortable margin on February 5 – will remove the requirement for casino owners with a thoroughbred licence to actually stage horse racing.

Decoupling has already wreaked havoc on harness racing and quarter horse racing, essentially ending those industries in Florida, while greyhound racing was outlawed in the state at the end of 2020.

Stronach’s comments about “dense, urban” environments reflect the fact that city racecourses are often in prime locations ripe for development.

The United States has seen a host of city racecourses shut down in recent years.

Stronach Group closed Golden Gate Fields in San Francisco in 2023 with the intention of consolidating racing in California to the south of the state – a strategy they admit has failed – while they also intend to shut Laurel Park on the outskirts of Washington, D.C. with Maryland’s industry to instead coalesce around Pimlico in Baltimore.

Beyond Stronach, Arlington Park in Chicago and Suffolk Downs in Boston have been razed while another former Los Angeles track – Hollywood Park – is now home to the gigantic SoFi Stadium.

All is not lost, though. There is more than a billion dollars currently tied up in racetrack reconstruction in the United States: $500 million to rebuild New York’s iconic Belmont Park, $400 million to renovate Pimlico and $100 million for Keeneland and Churchill Downs in Kentucky.

It is not just an American issue. In a world where land use in urban areas is under increased scrutiny and prime real estate is scarce, racecourses are an easy target for developers.

Racing in Singapore ended after 181 years in October with Kranji Racecourse reclaimed by the government for housing. The industry had already relocated from Bukit Timah, right in the heart of one of the world’s densest countries, in 2000.

Australia may be at the opposite end of the spectrum to Singapore as far as density goes, but it is also facing the same issues in its major cities.

The next few months will determine whether Sydney’s Rosehill Racecourse will be sold off in a bid to remedy the city’s housing crisis.

In Melbourne, Moonee Valley will close for redevelopment after this year’s Cox Plate. The entire track will be reoriented with a new grandstand built near the current 800-metre mark and the current grandstand area will also be developed into housing.

The history of racecourse development shows that nothing is certain yet ∎