The Final Singapore Derby And The Tragedy Of Kranji’s Unfulfilled Promise

Racetracks are more than just big betting shops and Kranji’s closure will mean a piece of Singapore’s soul will be gone forever. Michael Cox’s trackside account of the last ever Singapore Derby.

IT WAS SAD, but somehow fitting and hardly surprising, that when the gates opened for the final Singapore Derby, 144 years since the city’s first, the Singapore Turf Club wasn’t accepting paying customers.

By Race 2 there were already hundreds of fans, new and old, stuck outside and sweltering in 50-metre-long queues. Some watched races on phones, others turned on their heels and walked away. A German couple visiting the city for the first time stood, befuddled, “I can see why they are going out of business,” one said.

Tickets were free, but needed to be downloaded online before arrival, so there were no free tickets available at the gate. A fan asked “but can we just pay to get in? “Sorry, cannot,” he was told by an equally confused, apologetic and soon-to-be redundant attendant, as the ticket window dealt with customers one-by-one. Facing an hour-long wait, many fans went home, never to return.

At 1.30pm, a second and third ticket window opened, free tickets were hastily printed and dispersed. Cue sarcastic jeering from the crowd and the bottleneck cleared, but the dysfunction speaks to the tragedy of unfulfilled potential that is – and soon to be ‘was’ – Singapore racing.

At the entrance, first time racegoers and hardened old-timers alike had stopped for photos in front of the Singapore Turf Club sign at the main gate; inside, the concourse and grandstand buzzed like old times. Concession stands did a brisk trade on Singaporean street food offerings. The betting window queues ran 10- and 12-deep. It’s a pity that it took the imminent closure of racing in the city to generate this kind of interest.

For some, the last ever Singapore Derby was a reunion, as many overseas visitors flew in for the day to meet with old friends. Others will return on October 5 for the final meeting, for which seats are already being booked fast. Alongside the nostalgists, selfie-taking youngsters were also in abundance, their curiosity obvious as they absorbed the sights, sounds and smells of a soon-to-be-forgotten sub-culture of the city.

At the back of Grandstand 1, the regulars took their lucky seats. Top corner, left side, close to being in-line with the winning post, perched on a stool is Awang, who has been betting from the same spot since Kranji’s grand opening on March 4, 2000. “And before that I attended the races in Bukit Timah,” he says. In front of him on a bench are a couple of inch-thick bundles of blank betting tickets wrapped in elastic bands, a palm-sized calculator, some empty takeaway coffee cups and a half-finished can of root beer. He is quick to offer a filterless Marlboro from an old-style cigarette tin, politely declined.

“I am a heavy smoker, one day, two packets,” he says, staring ahead at the infield big screen, jotting shorthand notes as the horses are shown parading for Race 3.

“He likes to take notes,” a friend teases. “But just because he has a calculator doesn’t mean he knows what he is doing.” Awang scoffs at the suggestion, “I love looking at sectional times, a friend and I studied handicapping books and we taught ourselves,” he says. “I have been doing it for many years. Would I still be sitting here for all of these years if I was losing?”

He has seen a lot, Awang. Best trainer? “Ivan Allan”, The man whose global vision, drive and charisma ran central to Singapore’s rise to professionalism and abundance. Best horse? Rocket Man, trainer Pat Shaw’s world class Kranji-trained sprinter. Jockey? Joao Moreira, the Brazilian who in his own way put Singapore on the world map and then conquered Hong Kong.

“And I loved Saimee,” Awang says of the eight-time champion Saimee Bi Jumaat, a local hero. “OK, I need to concentrate now,” is Awang’s polite way of moving us on so he can get on with some serious study.

Race 3 is won by Sydney-based jockey Tyler Schiller, a 25-year-old rising star on a fly-in, fly-out basis and on his first trip out of Australia. He is the type of jockey that would have once used a stint in Lion City as a chance to grow his reputation and bank balance in the same way Corey Brown, Noel Callow, Vlad Duric and Michael Rodd did from Down Under over the past two decades. Legends Mick Dittman and Malcolm Johnston produced lucrative late career stints here. Fellow Australian Dan Beasley made a whole life in Singapore, riding more than 600 winners over 15 years.

That pathway and those opportunities will soon disappear. Neighbouring Macau is already consigned to history. Asia’s pathways for talent have narrowed. Now the only option for a jockey of Schiller’s stature is straight into the deep end of Hong Kong. Maybe even the transcendent talent of Moreira would not have handled that: in Singapore, where the ‘Magic Man’ nickname was born, the Brazilian had more than 700 wins, including 24 feature victories and three premierships in five years; not to mention that he learned English here. Singapore was his finishing school in more ways than one.

The crowds have shrunk in Singapore since those Rocket Man and Moreira glory days, and there is an official crowd of 5,800 for the Derby, but pound-for-pound, is there a noisier and more engaged crowd than Kranji? Maybe only Mauritius, another Asian jurisdiction under threat, could give the fans here a run for their money. Later they are in full voice when the reigning champion apprentice and Singapore’s only female rider Jerlyn Seow wins her 18th race of the year.

It is an accomplished ride from the 30-year-old but the time and effort Seow put into her promising riding career could be wasted. Where is she going to go? Malaysian racing prize money is poor and its standard comparatively low. Australia is a long way from home. Seow’s warm personality and winning smile would make her a fan favourite in Japan but, like Hong Kong, it is a tough circuit to break into – and even harder to conquer when there – for even the most talented young riders.

In June 2023, the Singapore government announced racing in Singapore would cease, citing a housing shortage, and the propaganda line that was pushed – and has been repeated ad nauseam via a pliant local press – was that racing is a dying sport with an aging fanbase the world over anyway.

The lazy narrative ignores that Singapore’s regional neighbours Hong Kong, Japan and Australia are thriving. They are jurisdictions that face what are arguably bigger individual hurdles, but they have evolved and used savvy marketing campaigns and investment in racecourses to stay relevant to new demographics.

The Singapore government-pushed narrative also ignores that turnover has risen in those similarly structured jurisdictions in the last decade. What is more baffling about the decision to shutter Singapore racing is that turnover also rose here the year it was announced it would be closed.

The bottom line is that Singapore racing should work. The Singapore Turf Club (STC) was given the key attributes that nearby Hong Kong Jockey Club (HKJC) and the Japan Racing Association (JRA) have used to become global giants of the sport: protected parimutuel betting with bookmakers banned, sports betting limited and under the control of racing, highly regulated racing and purpose-built training centres that should ensure watertight integrity.

In many ways, as a designated space, Kranji Racecourse and its stables are a better version of Sha Tin. While Sha Tin Racecourse was built on a relative sliver of land, 70 hectares reclaimed from the muddy delta of the Shek Mun River, Kranji is on a lush 120 hectare facility peppered with iconic rain trees and bustling with wildlife. The air is fresh and there is plentiful grass. Sha Tin is a concrete jungle, but away from the grandstands Kranji feels like an actual jungle when you see Bird’s Nest Ferns and Staghorns dripping from the Rain Trees, a monitor lizard lazing in the sun and an otter (yes, there are otters) shimmying between ponds in the infield.

Noticed on the last Derby day were the many young people – more rare than an otter sighting in recent years – enjoying those spacious surrounds and, after they dodged the free ticket debacle, last seen wandering around and wondering how to place bets. Unlike Japan, where a regularly scheduled ‘Racing 101’ seminar helps the novice racegoer, there’s nobody greeting newcomers here.

“It’s much more modern and nicer than I thought it would be,” says 24-year-old Wei-ting, who is at the races with her boyfriend Kaiser. “Because racing is associated with the older generation here, I thought it would be more run down. But it is clean and modern.”

Like many young Singaporeans, Wei-ting and Kaiser will soon be wondering how to break into a housing market in a city that is fast running out of space and a ruling government that is keen to keep its populace onside.

“It is sad to see it go but I can see why they are closing,” Kaiser says. “After all, it is Derby day, this is a big day, and there are still a lot of empty seats.”

Further around the seating in the first class parade ring, the iconic giant fans slowly turn above and another Kranji veteran looks at the runners for the next race, his wise eyes peering through “12 x 50” Nikon binoculars.

“When this racecourse closes I will be very unhappy,” says Richard. “In human life, you need to be happy. You come here to play and have fun. Tourists would come here too, it was known throughout the world and a great thing for the city. The Turf Club isn’t just for gambling, it is a place to enjoy yourself, to be outside and be with your friends.”

Richard’s phone rings. “It’s a tip, hold on” he says before lifting the phone to his ear for a critically important two-second conversation. “Numbers two and four,” he says matter-of-factly, before darting to the busy queue at the tote windows.

Out front of the grandstand, 21-year-old Harrie has a Silence Suzuka tote bag slung on his shoulder and is holding a JRA ‘plushie’ of Air Messiah. He is watching the races with his friend Grey.

So, given the complete lack of visibility afforded racing by way of marketing in the city, how does a young Singaporean become a fan of the sport to the extent he knows a relatively obscure Japanese racehorse from more than a decade ago?

“Air Messiah is in the game Uma Musume: Pretty Derby,” Harrie explains, referring to the cult anime series and highly detailed mobile phone game that features anthropomorphised versions of real life horses like Silence Suzuka and Air Messiah and has netted more than US$1billion in revenue for its creators CyGames.

“I played Uma Musume for two years before I thought, ‘Hey, maybe I should go and watch real horse racing’,” Harrie says. “And then out of nowhere I saw in June last year that horse racing would be closed in Singapore in 2024 and I thought ‘What?! Why, why?’ Just when I got into racing and tried to educate myself, they decided to do this. I was a bit disappointed.”

“I mainly focus on Group races from around the world,” Harrie says, going on to explain the structure of Group races in a way that plenty of racing administrators could learn from: “Horses start to move through open races first, then Group 3, which are for up-and-coming stars. Group 2s are like domestic championship races – if they can win there and get on a roll, the owner and trainer can try for Group 1s – and Group 1 is only for the very best, this is where horses can become super famous.”

Harrie can drop some pedigree knowledge, too. “Later today, there is a runner in the Derby, Jungle Cruise, who is by Jungle Pocket, who is in Umu Musume. Air Messiah was one of his ‘wives’, she had a foal by Jungle Pocket called Air Muscat.”

A quick cross check proves Harrie right: and Air Muscat herself is a successful broodmare, a grand dam to the temperamental but talented Classic winner Al Ain. Harrie knew that already.

So here’s a 21-year-old learning the sport at a deep level from a mobile phone game and anime series, but racing is a dying sport? Maybe if you let it be.

The Derby itself is one for the ages. Sadly, it may not be remembered as much as some of the great Derbies past because there will be few here to retell the story, let alone listen to. That goes for all of the Derbies past: the nine wins to Ivan Allan, the five to big money owner Jerry Sung, they could all just be names that will fade away.

Rich, dedicated owners are something Singapore racing has never lacked and it is fitting that the city’s last Derby was a classic won by one of its biggest supporters.

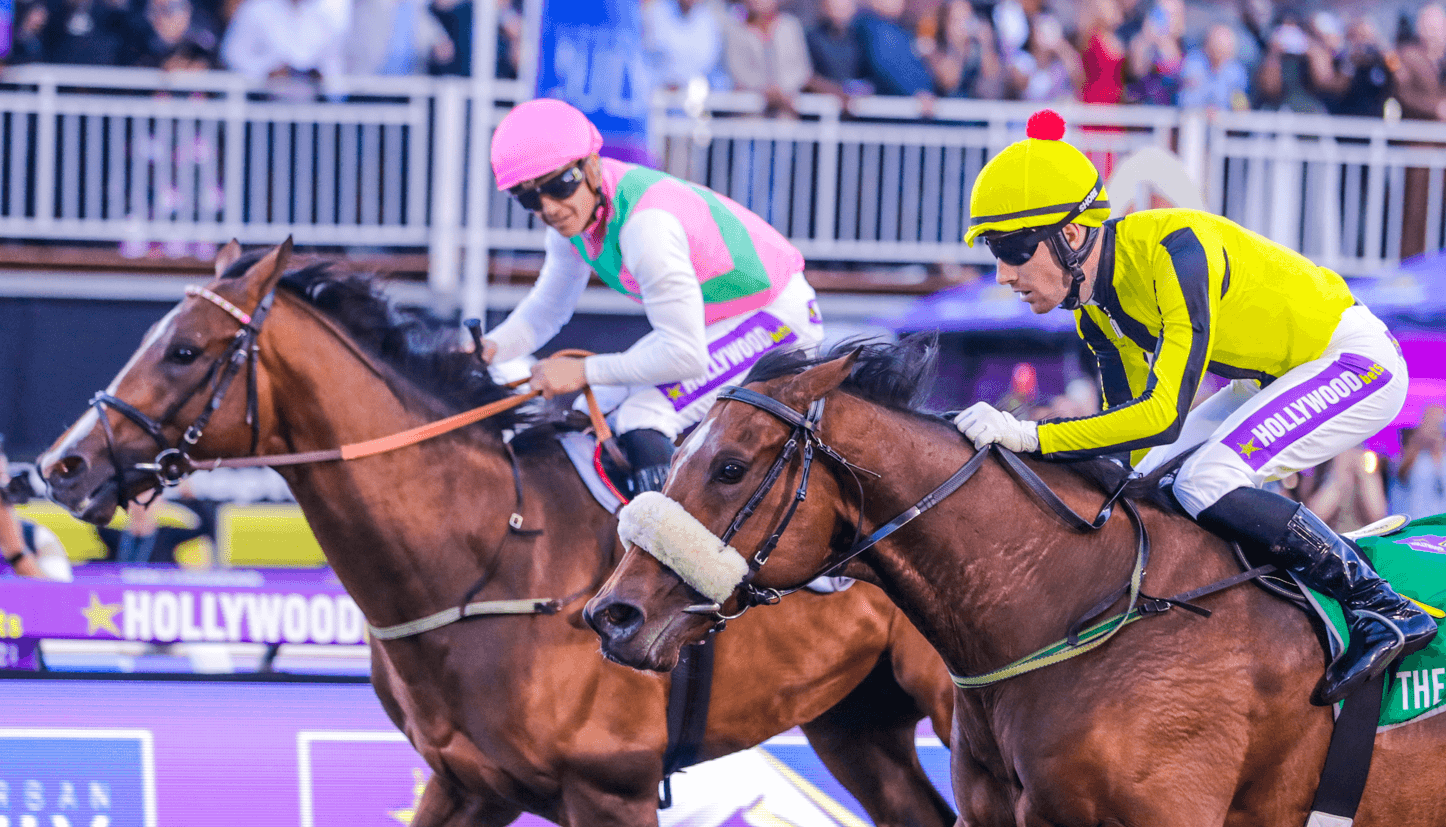

When Lim’s Saltoro prevailed after a head-to-head late race skirmish with Makin, it gave owner Lim Siah Mong his second Derby victory in three years.

Winning trainer Daniel Meagher’s family has been part of racing in the city for 24 years, first with his Melbourne Cup-winning father John, and then on his own as a successful trainer since .

Meagher will forever be the trainer of two of the last three Singapore Derby winners – Lim’s Kosciuszko won it in 2022 – both for “Mr Lim.”

“I got a bit emotional up there at the presentation,” said Meagher, who will return to Australia to train with his brothers Chris and Paul out of 40-boxes at Pakenham later this year.

“It wasn’t just Singapore closing that got me, but it was thinking back to all that my family have been through in the 24 years here in Singapore.

“To do it with Mr Lim, who was dad’s biggest owner, to win it for him: that means a lot.”

As the last race of the day begins, racing fans Clive, Muthu and Jackson have been waiting for their favourite: Australian jockey Hugh Bowman and the real reason they believe he is here, to ride Te Akau Ben, a horse raced via syndicate by New Zealand’s biggest owner David Ellis.

“He is a champion rider, one of the best in the world,” explains Jackson. “He only had three rides, one in the Derby, but we didn’t like the Derby horse or the other one he was on. Surely he would win one race today though, he is too good, and we liked the form of this one.”

As the race builds momentum, the trio’s fist-pumping becomes more intense, the cheering louder, followed by the familiar site on racecourses the world over: a round of joyous high fives among mates who have just backed a winner.

It’s a nice memory to leave on, albeit one clouded by that lingering thought of what could have been.