Masa Hashizume’s Unlikely Journey … And Now, Maybe, The Melbourne Cup

From troubled teen to waiter in a Japanese restaurant and now potentially a Melbourne Cup ride, Masa Hashizume has found direction in racing.

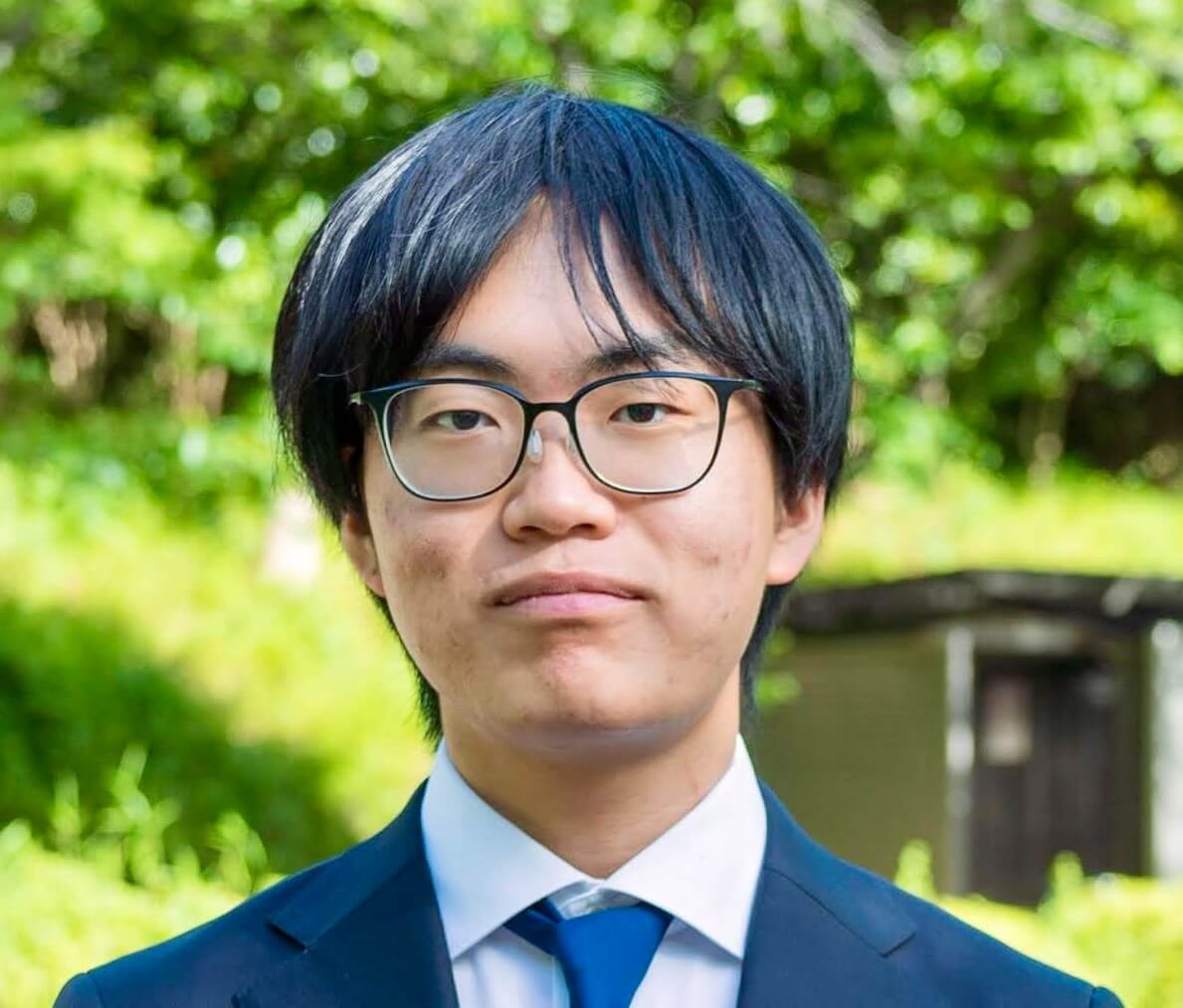

A SCATTERED CHILDHOOD MEMORY, more a series of stills than a film reel, sits in Masahiro Hashizume’s mind. It is a hazy recollection that sparked a journey that may end in some of the world’s greatest horse races – and to a test against some of Japan’s most famous riders – in the weeks and months ahead.

It was when a three-year-old ‘Masa’ made a first trip from his native Fukuoka – on the north side of Japan’s southernmost Kyushu island – down to New Zealand with his mother.

It was the first time that the toddler, an animal lover who was already dreaming of one day working as a zoologist, was exposed to horses. They embarked on a “horse trek” over hills and through country trails that delighted the young child.

“I had never watched horse racing at all, but my mother says that the smile on my face when I was riding the horse was very memorable,” Hashizume told Idol Horse. “I had always loved animals but I had never really thought about wanting to ride horses – I did enjoy patting them though.”

Fast forward 16 years and he was a troubled teenager without direction. The rebellious Hashizume was a frequent truant before dropping out of high school entirely.

“I was just messing around and both my parents were upset that I wasn’t going to school – we often clashed,” Hashizume said. “My mother brought up the idea of being a jockey and said, ‘If you aim to become a jockey, I won’t say anything else to you.’ This was a promise that even if I failed and gave up, she wouldn’t say anything further about it. For me, it wasn’t so much that I wanted to become a jockey – it was more that I just wanted to get away from my family.

“I took the JRA Jockey School entrance exam once, my mother applied on my behalf. I hadn’t prepared anything, had no connections, and hadn’t done anything – I thought I’d just take the test and that was it. I was probably number one among the people there in the physical fitness part, but I failed the first stage. I was ready to quit but she brought up the idea of going to Australia or New Zealand, which had been suggested by one of her clients. I didn’t want to go to either place but she said, if I went for one year and didn’t achieve any results, I could come back and live my life the way I wanted.”

And so it was that Hashizume traded Fukuoka for Christchurch in April, 2014, with little rationale for picking New Zealand over Australia and the assumption that they were essentially the same place. He arrived with no English, few warm clothes for a brisk southern winter and limited equine experience – certainly no horse racing knowledge.

“At first, I didn’t understand anything. I went to a language school for three months and, for the first month, I was just constantly watching people’s eyes as I didn’t know what they were saying,” he said. “I decided then I had to commit and I gained five kilograms and didn’t go out at all while just focusing on learning English. After that, I attended a horse school in Christchurch for about six months and then I found a stable and started working.

“However, racehorses and riding horses were terrifyingly different – you couldn’t categorise them together, they were that different. My first boss (Neill Ridley) was a nice person but was fully staffed and then the second stable I worked in didn’t suit me well, so I decided to quit working with horses. My visa was still valid, though, so I worked at a Japanese restaurant – I was a waiter and the sushi was delicious! – and I had fun.”

Hashizume returned to Japan for his traditional coming-of-age ceremony – a rite of passage undertaken by every Japanese adult who turns 20. For the one-time maverick, it marked a transition in a number of ways.

“I had started dating a New Zealand girl who came back with me for my ceremony,” he recalls. “A lot of people back in Japan were asking me about the horses and it hit me that I had gone to New Zealand for that purpose. We were based on the South Island but she was originally from Hamilton, on the North Island, and she was wanting to move back closer to her family. She also said that horses were more of a fixture up north and so we made the move.

“I approached several stables and said, ‘Please teach me to ride.’ And from there, when I was 20, I started riding racehorses seriously. I first trained in Cambridge for 18 months and then I was in Matamata for 18 months, I started riding in races during my last couple of months there. I was learning from a famous New Zealand jockey, Noel Harris, but we had different approaches – he was more instinctive and I take more of an intellectual approach. I understood what he was saying but it wasn’t the answer I was looking for.

“At that time, a former champion jockey Grant Cooksley was retiring to become a trainer. He told me that I had good balance and that if I could understand racing, I could become a good jockey. So I started working with Mr Cooksley and also Lance O’Sullivan and they have helped me develop and to achieve great results.”

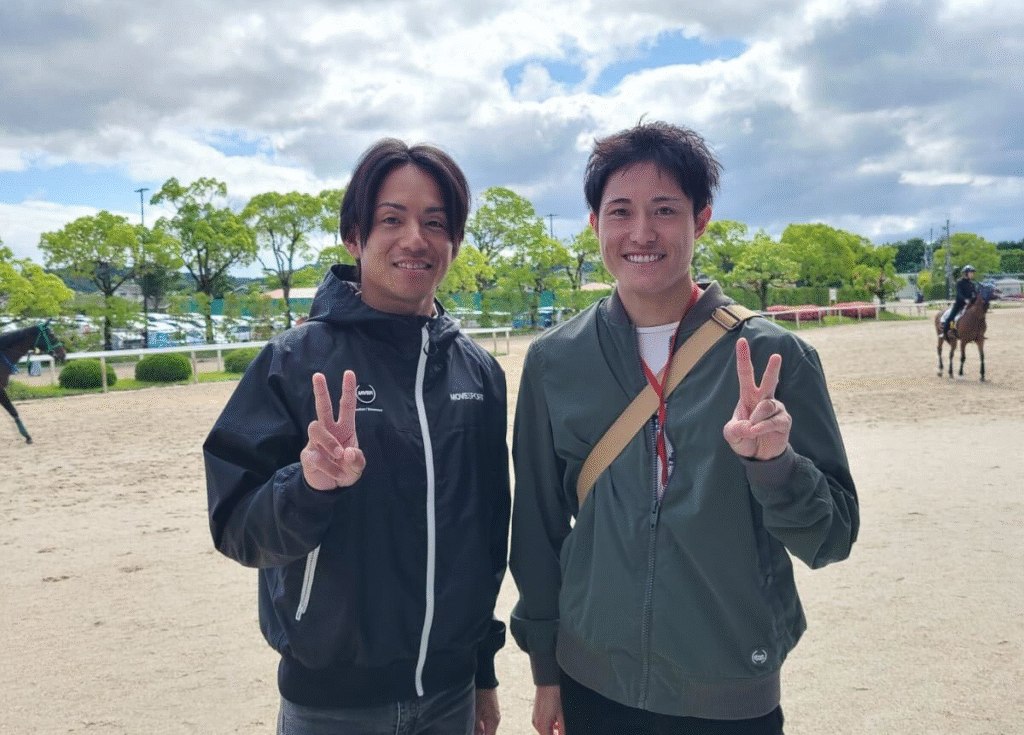

Hashizume is one of a number of Japanese jockeys who emerged in New Zealand at about the same time five years ago, alongside Kozzi Asano – now based in Seoul – and Yuto Kumagai, who no longer rides.

Also among their cohort was Taiki Yanagida, Hashizume’s former housemate – affectionately nicknamed ‘Tiger’ – who died after a Cambridge race fall in mid-2022. Hashizume was back in Japan at that time and delivered a video eulogy from abroad at his memorial service.

“I lived with Taiki when I was in Matamata during my early apprenticeship and we became good friends who shared a lot,” he said. “He was actually the first person who taught me what you have to do with exercise and all the things that will make you a good jockey. He was so strict, he taught me so much, and I will never forget him.

“I have Taiki’s photo at home and every morning before I leave to do my job, I talk to him and tell him I will try and do my best.”

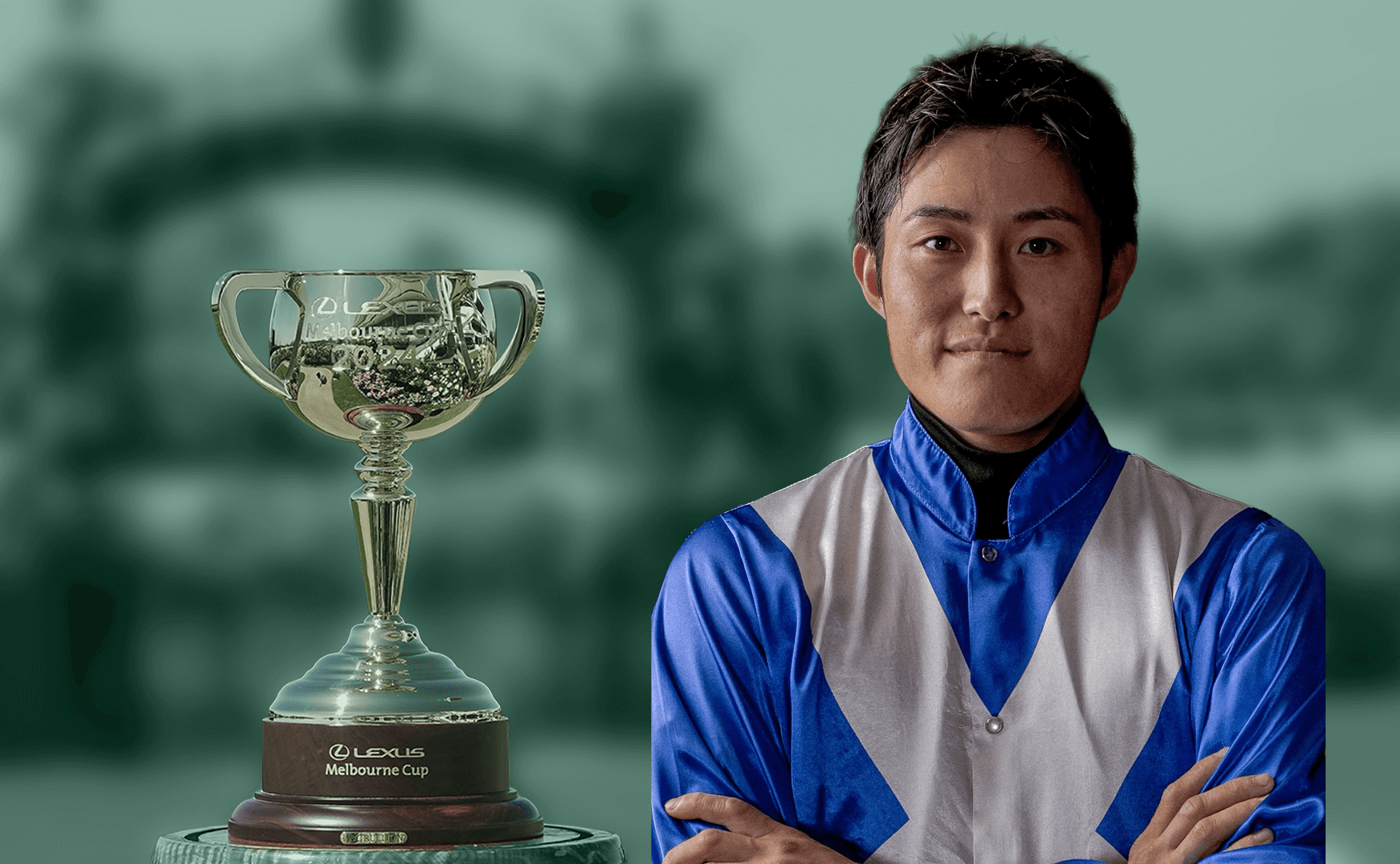

Hashizume is nearing 250 wins in New Zealand, including four Group 2 victories, and is making his Australian debut this spring aboard the Raymond Connors-trained Trav, with whom he combined to win the G2 Auckland Cup. The stayer is aiming at Australia’s most famous race, the G1 Melbourne Cup, and Hashizume hopes to maintain his association right through the spring – weight permitting.

“I usually weigh around 53 kilograms, so 51 kilograms – which is the weight Trav has been given – is not easy,” Hashizume said. “It’s probably been five or six years since I last made 51 kilograms but I will try very hard if he makes the race.

“Many Japanese riders seem to go to Australia first before coming to New Zealand. I probably would have gone to Australia first, too, if I had researched properly. Those who go to Australia first tend to use up their working holiday visa during their training period. If I get a chance to go to Australia for training, I’d still be able to go on a working holiday visa – maybe that could happen in the future.”

The Melbourne Cup could see Hashizume tackling some of the world’s most famous jockeys, including two of his countrymen – Suguru Hamanaka, booked to ride grey mare Golden Snap, and the legendary Yutaka Take, who is among those in contention to partner Chevalier Rose. It is a prospect which excites the 29-year-old, who hopes to partner his first Group 1 winner in the coming weeks too.

“Riding with good jockeys is the most fun,” he said. “During the New Zealand season, there are times when the best jockeys come together and times when no one is around. But the big meetings where all the good jockeys gather are always fun to ride in.

“I have a goal of riding a Group 1 winner this season – it’s not something you can control, but I hope that by treating each race with importance, gaining experience, learning what I can from each one and applying it again, I can win a big race.”

As Hashizume – now a father of two himself – prepares to join the ranks of globetrotting jockeys, he allows himself a moment to reflect on how far he’s come.

He thinks of that 16-year-old boy in Fukuoka, the one who had drifted so far off course until his mother reminded him of the simple joy he once felt – a boy who found his smile again on the back of a horse. ∎