Last week I asked readers what they wanted to know, and two questions kept coming back. The first was simple but confronting: who is the next superstar apprentice to come out of Australia? My answer is blunt. There isn’t one. And the reason isn’t talent – it’s the system.

Australia has become far too safety-conscious. Officials think they’re protecting kids, but what they’re really doing is killing the very thing that creates great jockeys: time on horses. The key is that you can’t ride trackwork until you are 16. You cannot start riding trackwork at 16 and expect to become a superstar. Sixteen is too late. Superstars are made long before that.

Look at every great performer in any field. Andre Agassi had a tennis racquet in his hand at two and was playing for money at 10. Musicians like Taylor Swift and Justin Bieber were performing publicly as kids. You don’t wake up at 16 and decide to be elite. It’s your whole life.

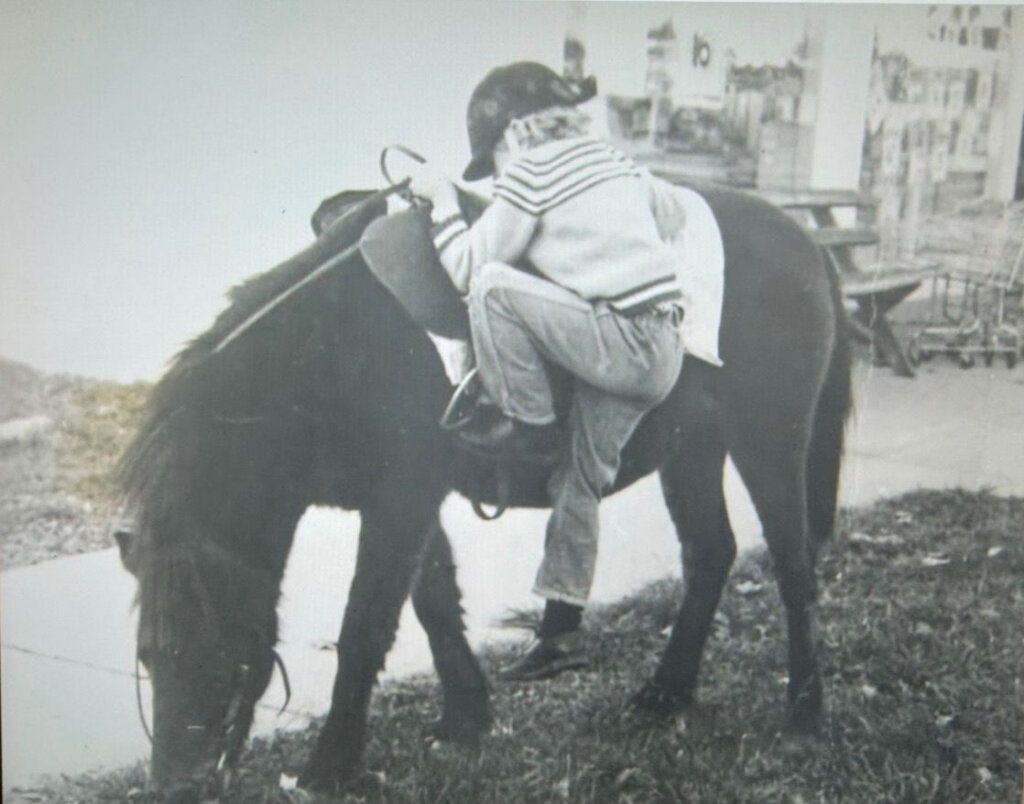

Granted, playing tennis and a guitar isn’t as dangerous as riding a horse, but I was riding ponies by three. There are photos of me on a horse at 18 months. I was falling off, had horses bolting and I was learning balance and dealing with fear before most kids could spell their own name. I rode trackwork at 10 and was riding Group 1 horses in gallops at 12 in Matamata. I took a day off school to ride in my first race, aged 15. But I’d already spent years learning instinctively how a horse moves, thinks and reacts.

I didn’t get “discovered”. I made myself. I wanted to be a jockey from the moment I was born. My grandfather was a leading rider, my father was a jockey, but plenty of kids come from racing families and don’t make it. What mattered was obsession. At 14 I rode my bike to trackwork at four in the morning, rode trackwork, rode my bike home, went to school, skipped breakfast to stay light, then did sit-ups and push-ups every day. I counted the days down until I could ride in races. Nothing else mattered.

Compare that to today. Kids aren’t allowed near horses in racing stables early. They’re told to wait. Just remember, the greatest jockey of all time, Lestor Piggot, was riding in races at 12. In Australia they’re suddenly thrown into stables at age 16, earning little money, working brutal hours, surrounded by mates who are partying and distracted. Drugs, technology, easy alternatives – it’s a different world.

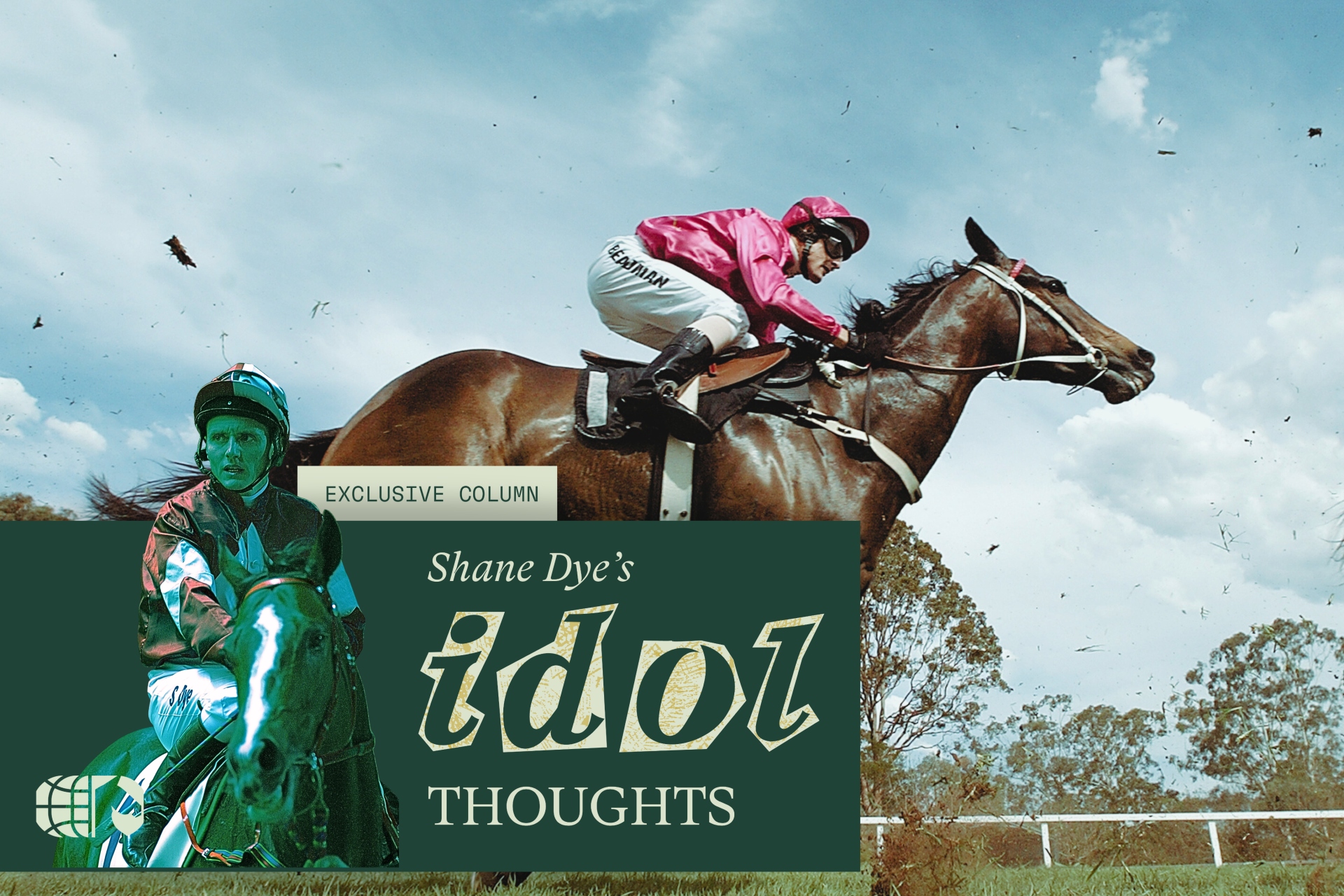

People ask why we don’t have apprentices like Darren Beadman or Darren Gauci anymore. The answer is we haven’t had a true superstar apprentice in Australia since the late 1980s. Damien Oliver was a very good apprentice who became a superstar jockey – that’s different. If the system was working, you’d see one every generation. We haven’t seen one in 35 years. That tells you everything.

In Britain and Ireland it’s different. Kids ride in pony races. They race as amateurs. They’re at the track every week, dressing as jockeys, learning racecraft by doing it. That’s why Europe is now producing better young riders than Australia.

Heading abroad can be an important part of a young jockey’s development – that is something European jockeys are doing, spending time in Australia or America – but I don’t see Australian apprentices doing the same.

And the other question: why aren’t modern jockeys as good as Lestor Piggot, Pat Eddery or Mick Kinane. Well, there is a modern Lester Piggott – his name is Ryan Moore. It’s no coincidence he grew up on horseback.

There are positives. Corey Brown did an excellent job mentoring apprentices in a role with Racing NSW and it’s no surprise Zac Lloyd, Tyler Schiller and Dylan Gibbons all emerged together when he was there. The Hong Kong Jockey Club also deserves credit. Given most kids in Hong Kong grow up with little contact with horses, the structure, overseas exposure and education they provide is outstanding.

But the big picture doesn’t change. If you want superstars, you need kids on horses early. You need instinct, balance and decision-making baked in from childhood. Safety matters, but over-protection is destroying the chances of the next generation becoming truly great.

Octagonal And Riding On Instinct

A reader also asked about my ride on Octagonal in the 1997 Chipping Norton Stakes, where I looped the field from last with more than 800 metres to go. Did I have a plan? No. None at all.

That’s the part people misunderstand. I didn’t go out there thinking, if they go slow, I’ll take off. It wasn’t in my head before the race, or even 200 metres after the start. It was a split-second decision. The pace was ridiculous, the horse in front of me was coming back at me and instinct took over. Boom. I had to go.

That’s how you ride to win. Every race you’re constantly asking one question: how can I win?

Sometimes you get it right, sometimes you get it wrong – but at that stage of the race it was the right decision.

James Orman And the danger of judging by results

Someone said to me after the weekend, “Gee, Jimmy Orman is riding well.” My answer was simple: he’s been riding well since he arrived in Hong Kong midway through last season – he’s just getting results now.

His double on Saturday gave him 11 wins for the season at better than 7.5 per cent and he has had five wins from his last 25 rides.

People confuse results with performance. They’re not the same thing.

I don’t just watch replays. I watch a replay of every horse in every race and I keep a list of bad rides. Jimmy Orman doesn’t appear on it. He’s consistent, calm, puts horses in the right spots and rarely makes poor decisions. That hasn’t changed because he rode a double on the weekend.

What Orman doesn’t do is just as important. He doesn’t panic when something goes wrong early in a race. He doesn’t get horses overracing.

The simple answer to what has made him successful so far is that he gives every horse every possible chance.

In Hong Kong, barriers, tempo and opportunity matter enormously. You can ride brilliantly and not win, and you can win while riding poorly. The trick is knowing the difference. Orman has always ridden to a high standard. Now the luck and results are lining up – and that’s when people finally notice. ∎