Neville Begg On Emancipation, Hong Kong And A Lifetime In The Game

Neville Begg knows: “One good horse lifts everything”. Emancipation did it, Hong Kong tested it, a lifetime in the game proved it. And at 94, the trainer who took on T.J. and Bart still carries the old truths.

Neville Begg On Emancipation, Hong Kong And A Lifetime In The Game

Neville Begg knows: “One good horse lifts everything”. Emancipation did it, Hong Kong tested it, a lifetime in the game proved it. And at 94, the trainer who took on T.J. and Bart still carries the old truths.

1 January, 2026NEVILLE BEGG sits in his high-rise apartment in the quiet, leafy east of Sydney, looking across Centennial Park to Randwick Racecourse’s billowing figs and the glistening Allianz Stadium, sunlight flashing off its futuristic skin. Through the north-facing windows is Sydney Heads – the gate where steamboats once brought horses down from Newcastle, the hard northern city of his childhood. In the corner, a small whiteboard carries the names of all the mares in his broodmare band, marked on individual magnetic pieces. At 94, through a lifetime in racing, Begg has lived history – and he isn’t done yet.

Every morning he sits at the same table and goes through the race records – results, pedigrees, bloodlines – “every race, every day,” as he puts it. The whiteboard isn’t nostalgia; it’s a working tool and the old master still moves its pieces with purpose.

“As long as you have some unraced horses, you have hope,” he says.

Begg’s lifetime spans many arcs: the wartime boy in Newcastle, young foreman to Todman, the Randwick trainer going head-to-head with T.J. Smith and Bart Cummings, a Hong Kong chapter, mentorships that echoed globally – and now, a late-career breeding renaissance.

And before most of that, there was a mare who lifted his whole world: Emancipation.

Begg’s Emancipation once wore the ‘greatest racemare ever’ tag, long before Black Caviar and Winx. Willful, fiery, destructive in the stable but unstoppable on the track – six Group 1s and 19 victories in all.

Mid-conversation, the phone buzzes. It’s son Grahame, calling from Melbourne with an update on a horse he is training – one bred by his father. Begg listens, nodding, saying little, but his chosen words echo with the authority of decades. “He’s done very, very well,” Begg says of his son afterward. “He strapped Emancipation all her life, took her interstate, and did a great job with her. He hit hurdles, but he’s built a good stable now.”

Grahame once described Emancipation as “the worst tempered racehorse imaginable” – his father doesn’t disagree.

Begg always suspected Emancipation’s temperament came from her pedigree as much as her personality. “She wasn’t what you’d call inbred,” he says, “but she had two crosses of Star Kingdom in her … maybe that worked against her temperament-wise.” Whatever the cause, the result was unmistakable: “She’d kick, bite, smash the stable to pieces,” Begg laughs. “But she was a great race mare.”

For Begg, one truth endures: the power of a good horse.

“If you get one good horse in the stable, it lifts a whole bloody stable,” he says. “The people respond, the horses respond. Everything’s positive when you’ve got a good one. You miss them when they’re gone.”

Begg became known as a master of fillies and mares, winning 10 Oaks around the country. “We were lucky enough, we got known a little bit as a fillies’ trainer,” he says. But the truth was simpler: he gave all of his horses time, patience and trust.

That kind of horseman doesn’t come from nowhere. Begg’s story began in Newcastle, born in 1931 into a steelworker’s family. His father laboured in the nut-and-bolt factory at Wickham; young Neville worked there weekends from the age of 12.

“I’d weigh up the bags, stitch them and I could run the machines,” he says. “They were tough old times. The rabbit man would come around selling rabbits, sixpence each. The clothes-prop man would come round. The dunny man with his cart. People would pick blackberries to make a living. Our street had one car; the rest of the people were on horses and pushbikes.”

The family home had no hot water. If you wanted a bath, you’d boil a copper full of water and carry it to the bathroom. His mother washed sheets in a kerosene tin, plunging them down in the water. No washing machines. It was a hard life, but Newcastle bred achievers.

War was a defining presence in the city, whose steelworks made it a target for Japanese submarines.

“When they announced we’d gone to war, my grandmother cried,” he recalls. “She’d lived through the first war and knew what it meant. My mother dug an air raid shelter in the backyard herself. We covered it with earth and sat on benches underground when the sirens went.”

The city was ringed by both industry and, as the impact of the Great Depression dragged on, ‘unemployment camps’ – shantytowns that sat side-by-side with factories.

“The gas and coke works – the men used to come home every night with their throats full of arsenic, drink a pint of milk just to clear it. It was tough work.”

Yet the neighbourhood bred champions. Clive Churchill, rugby league’s ‘Little Master’, grew up around the corner. An acclaimed neurologist named Billy Burke lived in the same street. In a twist of fate, Burke would later work on Begg’s son-in-law Wayne Harris when he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. The famous ‘Fighting Sands Brothers’ – Dave Sands was a boxing legend – trained in a Beaumont Street gym, a few blocks away. “I used to go there as a kid, get in the sweat box, put the gloves on,” Begg says.

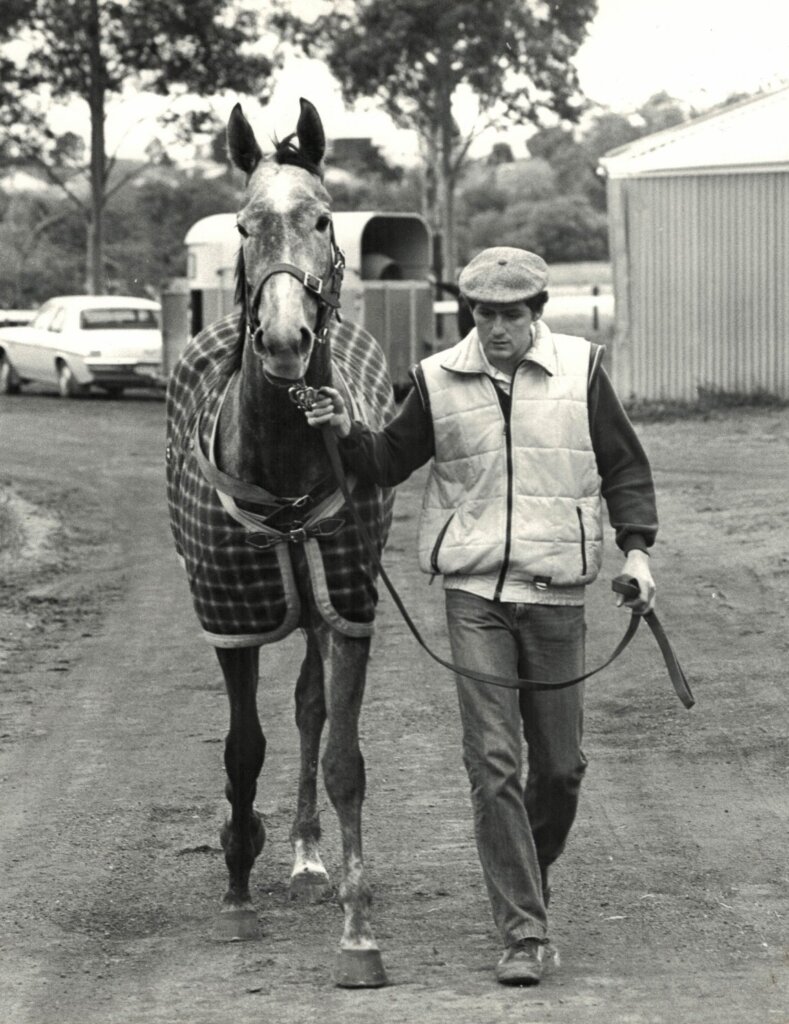

By 14, Begg was riding trackwork across the road at Broadmeadow and, not surprisingly, the work was hard. “A trainer brought three horses up for the Cup – they came up by boat. I met them at the wharf on my pony and led them back to the stables.”

By the time he turned 15 it was time to move south. “When I left school, I came straight to Sydney because you had to sort of get into the big smoke to do any good. There wasn’t much going on in Newcastle at the time.”

At 15, in 1945, he went straight to Maurice McCarten’s Randwick stables, unannounced.

“He didn’t expect me,” Begg remembers. “Had to find me a bed. But I stayed 22 years – the only job I ever had. We had to do everything: muck out, saddle, walk the horses down to Randwick. Ten shillings a week and half a day off every second Sunday. I think I had one week off in all that time – when I got married.”

McCarten’s stable was a nursery of champions. Begg was there as foreman when Todman won the first Golden Slipper in 1957, a horse many still call the greatest two-year-old of all time. He handled Delta, Wenona Girl, Noholme. He learned to do everything right, and all of it himself.

“I saddled every runner. Might have three or four in the race, but I’d saddle them all. I wanted to make sure everything was right.”

McCarten was brilliant, but difficult, and eventually Begg branched out on his own in 1967. His first runner won.

Soon Begg was Sydney’s leading rival to T.J. Smith. Despite a massive numbers disadvantage against Tulloch Lodge, the original ‘mega stable’, Begg held his own. But ultimately he finished second in the standings nine times during Smith’s remarkable 32-year reign – “Tommy said once, ‘Neville’s a good trainer, but he can’t train his owners.’ He massaged owners, I never did. I was naïve.”

Bart Cummings arrived later from Adelaide and Melbourne, chasing Cups. Les Bridge, Brian Mayfield-Smith and a Rosehill surge all added to the mix. “One year those Rosehill trainers were winning everything. We were flat out trying to get a winner. Then they all disappeared.”

Begg’s stables, Baramul Lodge, became synonymous with class fillies and tough mares, November Rain and Dark Eclipse were also stars, but he could train colts to stallion careers too – crack staying colt Veloso and runaway Epsom Handicap winner Dalmacia count among a long list of black-type winners. Yet it was Emancipation that defined him. “When she left, I felt it. You do miss them.”

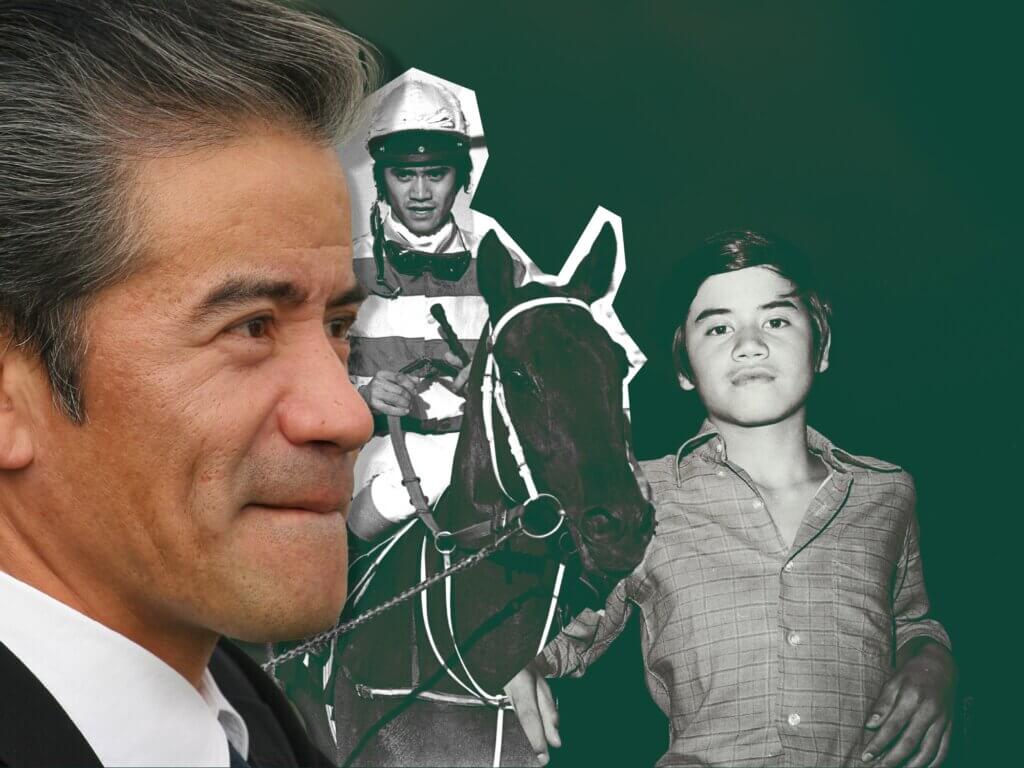

Among the many young horsemen who passed through Begg’s Randwick yard was a Japanese worker who would later change the face of world racing: Yoshito Yahagi.

“Well he was the finest bloke you could ever see,” Begg recalls. “I don’t know how he came but Yoshi was with us for a while. I think he was actually sweet on me eldest daughter a bit, you know. I’ve seen him a few times since, at the sales and that. He speaks good English, Yoshi.”

The young Japanese man who once mucked out boxes in Sydney is now a global figure, a Cox Plate, Breeders’ Cup Classic and Japan Cup-winning trainer.

“He’s done amazing. When you see the numbers of horses he is allowed to train there, for him to get the results he’s getting – it’s not like Australia or England where they’ve got 300 horses in work. I couldn’t believe it when I saw him winning those races. Unbelievable.”

‘Yoshi’ was with Begg for about six months, long enough to share dinners at the family home. “He wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth,” Begg says with obvious admiration. “He’s come up through the ranks.”

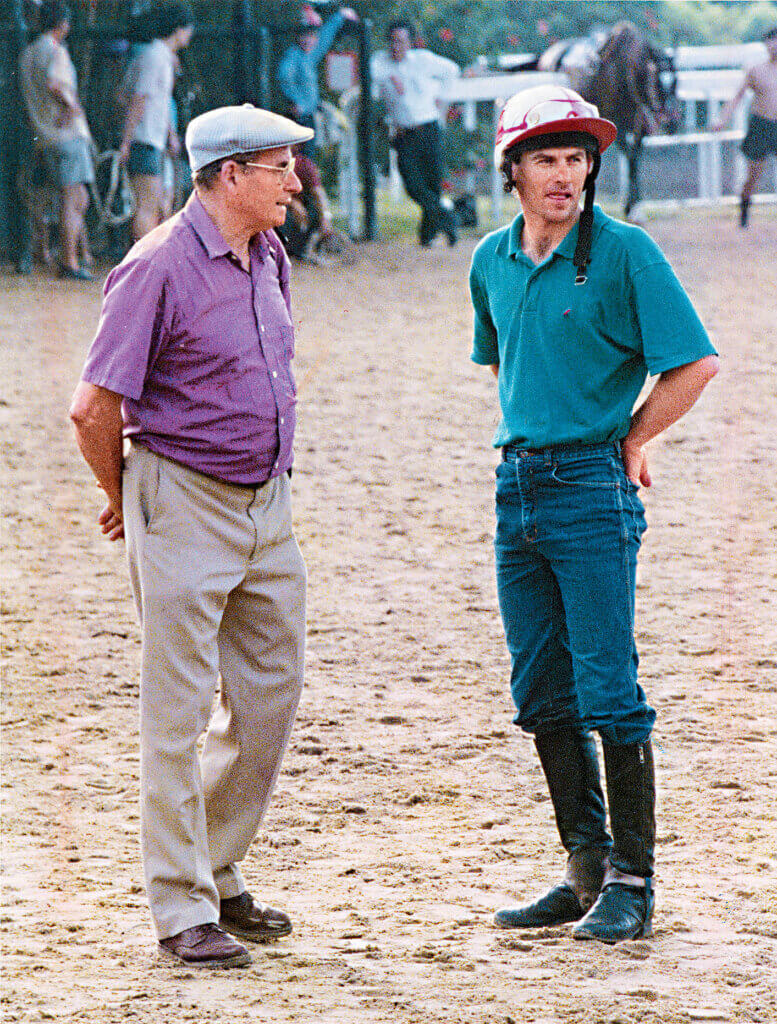

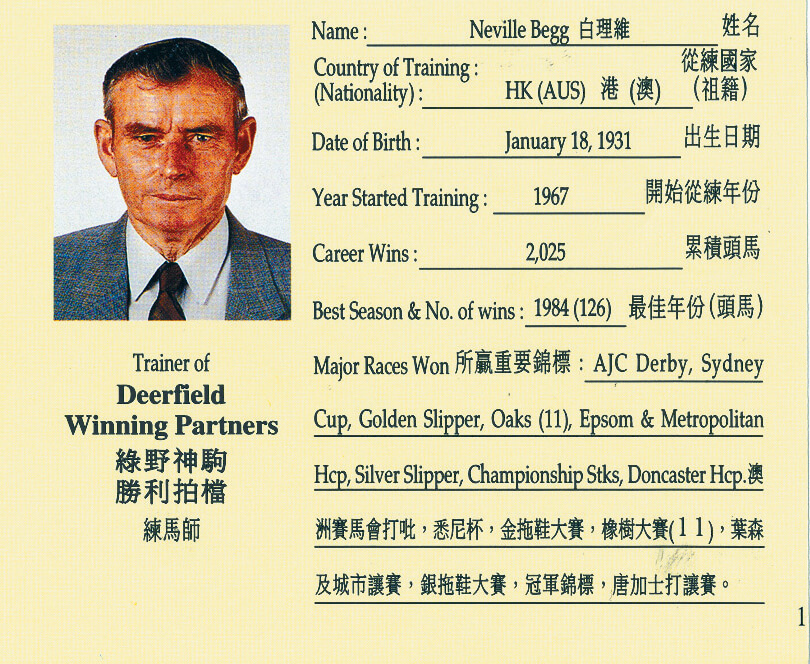

In 1989, after training more than 2,000 winners, Begg uprooted himself from Randwick and landed in Hong Kong. He was 58 and it was the first time he and wife Yvonne had travelled abroad and been away from their six children. The hair-raising descent into Kai Tak Airport above Kowloon City welcomed them to another world.

“They gave me an empty apartment at Racecourse Gardens. We bought furniture, sent them the bill, and they paid for it. I had to shut my Sydney stables quickly. Grahame got half, Billy Mitchell the other half.”

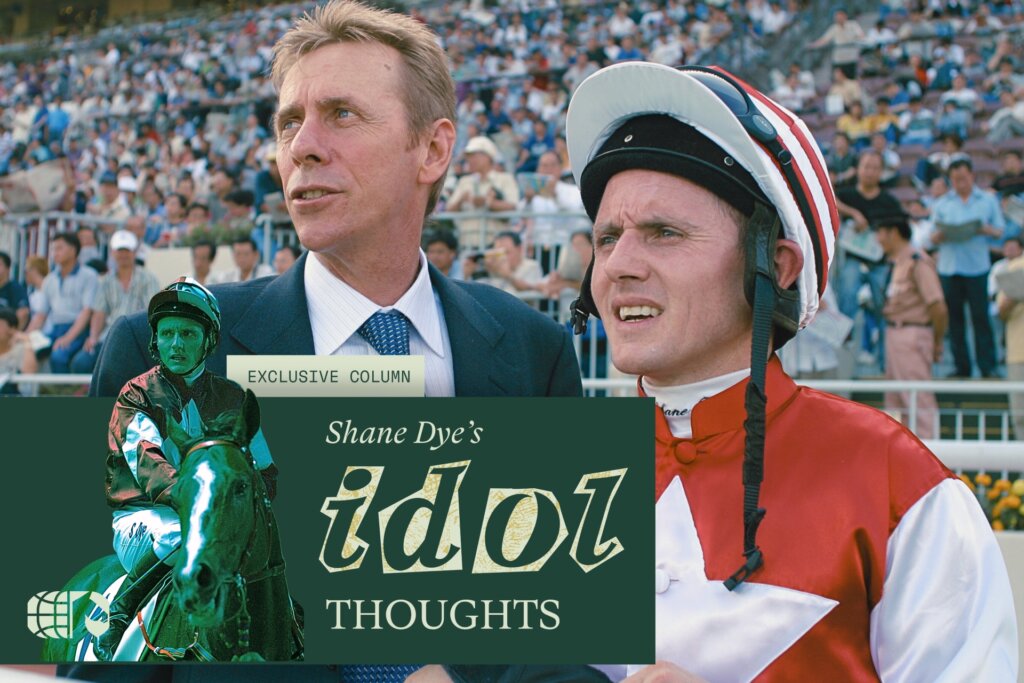

His first year he wasn’t allowed to bring a jockey. “I wanted Mick Dittman, but they knocked him back. Later I had Robert Thompson, a great jockey but the locals didn’t like him as much – too much of an Australian country boy – then Darren Gauci. Darren was outstanding – the best boy you could deal with.”

What struck him most was the different balance of power. “The assistants were the key. The most important person you had. Owners spoke Cantonese to them, not to you. Francis Lui was my last assistant … a very quiet bloke, but a good one,” he says. Lui would one day be champion trainer and prepare the mighty Golden Sixty. “Some assistants rise and some don’t – he did.”

Begg recalls the street politics vividly. “Ivan Allan had a horse get beaten, blamed the mafoo, put another mafoo on, and the horse improved. He told people, ‘The mafoo was no good.’ Next thing, the mafoos surrounded his stables – hundreds of them chanting. From my apartment you could hear it. They were going to lynch him.”

That was when trainer Brian Kan stepped in. “Brian was volatile, but he was a village chief. He walked out in his slippers and dressing gown just as the crowd was ready to riot. He gave them a blast, and next thing they were all gone. He had that authority.”

Living in Hong Kong was like a fishbowl. “They used to tap all my phones. All the waiters, the car park boys, they were punters. The triads controlled all the valet boys. They’d copy your car keys, follow you home, pinch your car. If you went to dinner with somebody, someone was reporting on you.”

Still, Begg thrived and was a popular presence over a short but successful six-year stint in the city. As an owner, he won the Hong Kong International Bowl back-to-back with Monopolize – trained by Grahame. “I am still the only trainer to own the horse that won an international race there.”

The conversation circles back to family. Yvonne, who passed away in 2023, kept the books and raised six children while Neville worked dawn to dusk.

“She did everything,” Begg says, his voice softening. Carmel and Linda, his daughters, are still at his side. And Grahame, based in Melbourne, carries the family’s training tradition into another generation.

And even now, in his mid-nineties, Begg’s days are animated by the optimism of new horses and new matings. One small grey mare sits at the centre of it: Yau Chin, a $3,000 filly he spotted at the Scone Sales in 2007, decades after Emancipation.

“I was on my way home,” he says. “Saw this grey filly down the paddock. Someone said eight hundred, someone said a thousand. I said three – and got her.”

She ran a few placings, then went to stud. She became bloodstock gold.

From a humble beginning came Written By, sired by champion stallion Written Tycoon, who Grahame selected as a yearling and first trained himself. Written By failed to reach his reserve of $200,000 but Grahame trained him to a G1 Blue Diamond Stakes win.

Written By now stands at stud for $22,000 at Widden, and Begg owns 75 per cent – another lucrative living thread connecting the old master to the next generation of Australian horses.

“Yau Chin means ‘have money’ – or rich – in Cantonese. And she certainly lived up to her name,” he laughs.

A full brother was lost in an accident as a young horse – one of the rare setbacks in a line that has otherwise flourished. C’est Magique sold for $1.7m to Coolmore as a yearling. Yau Chin died last year but her legacy continues beyond the old whiteboard.

She wasn’t another Emancipation, but few are. What the story of Yau Chin encapsulates is something else entirely – the story of a man who is still building, still planning, still busy shaping the future.

Watching him, it’s not hard to see how Begg was so engrossed in his work that he never got around to obtaining a driver’s licence.

“I never drove a car in my life,” he says. “Couldn’t afford one when I was young and later the kids drove me everywhere. Linda and Carmel used to drive me to the races.”

There might still be time. Begg will be 95 on January 18 and is still going strong – his advice for a long and active life is simple.

“Don’t get old, that’s my tip,” he says. “But I’m still steady on my feet – and I keep moving forward.”

The afternoon sun shifts across Centennial Park. The figs at Randwick – some of them just saplings when Begg was born – tower over the course now, their branches moving in the breeze and casting shadows across Royal Randwick’s sweeping home turn.

Since that afternoon, the whiteboard in the corner had to be replaced; the broodmare band kept growing until the magnets outnumbered the space. Progeny off that board are now scattered through other people’s stables – youngsters with Grahame and a handful with former jockey turned trainer Dan Beasley at Wagga Wagga, learning their trade in the country.

For Begg, that’s the perfect arrangement: the horses moving out into the world, the old truths still holding, the man at the window still scanning results for his bloodlines, trusting that somewhere among them one more good horse might be waiting to lift everything again. ∎