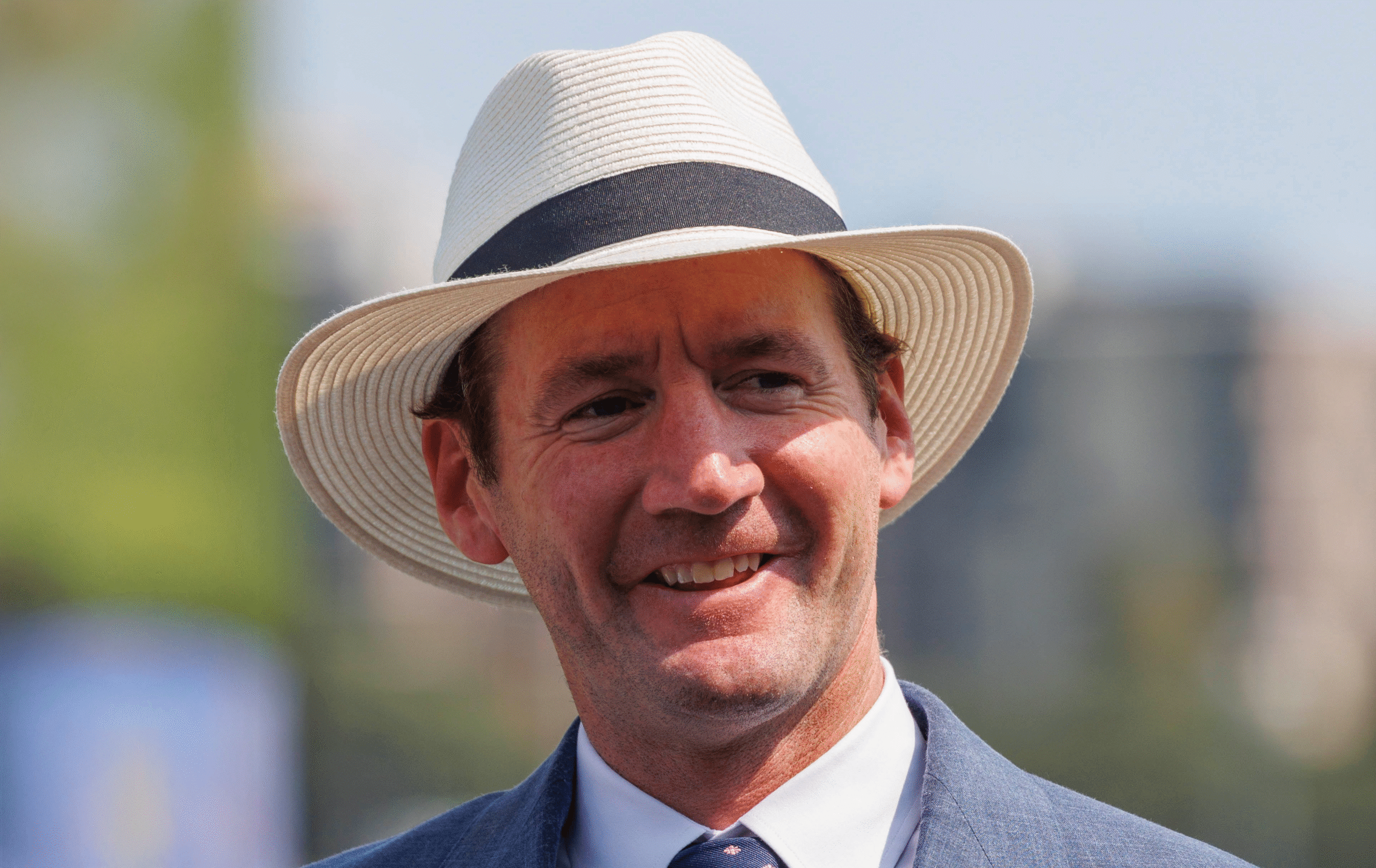

So, what if James Cummings had been told he could have the keys to Leilani Lodge, say, three weeks ago? Would he still have been unveiled this week as Hong Kong’s newest trainer? It’s a curious hypothetical.

“I just want to focus on the positives and not dwell on that at all,” Cummings says.

Horse racing survives on individuals forming opinions every single day. Form your own on that.

But it’s also an uncomfortable question the embattled Australian Turf Club board needs to ask themselves: just how has a fourth generation G1-winning trainer, whose family dynasty has sprinkled magic dust on horses housed at the famous stables for five decades, slipped through the fingers of Sydney racing at the age of 37 when he wanted to take over Leilani Lodge?

As the days dragged into weeks and no decision was forthcoming on the yard while the ATC bombed out on the contentious $5 billion Rosehill sale, the Hong Kong Jockey Club quietly reached out to Cummings. He was still searching for a base in Sydney to start what was going to be his new life as a public trainer from August 1.

It’s hard to see Cummings’ unveiling as Hong Kong’s newest trainer for the 2026-27 season for anything other than it seems: one of the biggest coups the Jockey Club has landed in years and a spectacular failure for Australian and Sydney racing, whose ageing training infrastructure was not flexible or big enough to quickly accommodate a free agent in Cummings, a man on course to challenge all the records if he stayed in Australia for the rest of his career.

It was only a fortnight ago a senior ATC official, when asked about the progress of a decision on Leilani Lodge, confessed: “James Cummings is vital for the future of Sydney racing”.

The Jockey Club was clearly listening.

While they were in front of the ATC to do a deal to lease their slot for The Everest and parachute Ka Ying Rising into the A$20 million race, at the same time behind the scenes they were discreetly recruiting Cummings.

Ciaron Maher is now the odds-on favourite to get Leilani Lodge, tipped to edge out Adrian Bott and his training partner Gai Waterhouse. The stables need work, and Maher has vowed to pour his own capital into the yard, whereas according to sources familiar with the process, Cummings pushed the envelope with the financially-challenged ATC board during his interview. Romance is nice, but it might not have been enough.

Maher has about 390 horses in work during winter, his horseflesh zig-zagging between beach, rural and city training centres in both NSW and Victoria. Scarily, he thinks he’s geared up for more growth.

And that’s the point: if a young, highly intelligent, presentable trainer like Cummings, who has racked up more than 50 Group 1 wins already and had his hands on the wheel at Godolphin for eight years can be squeezed out (or had his head turned elsewhere), then where will Sydney racing be in five or 10 years time? Half a dozen mega stables racing each other each week and that’s it?

Industry insiders say Maher’s expansion into NSW helps their bottom line. His runners have attracted a loyal following of Victorian-based punters familiar with his feats, and on a per runner basis, his horses have a significantly higher wagering hold than most other Sydney trainers.

It’s important, but it’s not everything.

Australian racing has always been built on variety. Some of its most famous races like the Melbourne Cup and the Doncaster are handicaps, where theoretically every horse should have a relatively equal chance. It thrives on the stories of underdogs – be it trainers, owners or jockeys – who beat the odds.

A quick glance at Sydney’s meeting on Royal Randwick’s inner track this week hardly inspires confidence for the future. To put it into context, it’s the quietest time of the year for Sydney racing. But just six races with only 50 starters for the second best meeting of the week? It’s hardly inspiring.

Cummings’ intended return to life as a public trainer was supposed to spruce up betting markets, giving punters a familiar and trusted name to follow in the form, also knowing he’d been shackled by Godolphin’s dwindling numbers in recent years. That won’t happen now. They’ll just have to back his horses in Hong Kong.

To his credit, Cummings has always been attracted to the thought of training in Hong Kong, where his 12-time Melbourne Cup-winning grandfather Bart also prepared Catalan Opening to win the Hong Kong Bowl in 1997.

“Open minded,” he tells Idol Horse of the switch. “You never know what the future holds and the opportunity has come along, and we’ve all moved fast. It’s happened quickly. I guess I always had ambitions to one day be able to train here in Hong Kong. (Wife) Monica and I felt like it was a now or never scenario for us. It’s the decision we felt was the right one to make.

“Jockeys and trainers who have lengthy periods away really come back with gusto, I’ve noticed. I hope to make the most of that sort of momentum and use that time wisely.”

Cummings is a father of four children under 10. Their parents will support them in whatever path they want to take in life. Who knows, there could be a fifth-generation Cummings one day in the training ranks.

But if Australian and Sydney racing has lost dad indefinitely, will it ever be good enough to convince his son or daughter to make it home? ∎