“I Just Want To Get Back To Society”: Tom Prebble’s Most Important Race

In conversation with Adam Pengilly, 23-year-old Tom Prebble reflects on recovery, hope and finding purpose after the race fall that changed everything.

WHEN JAMES McDONALD jumped in the car after winning the Cox Plate for a fourth consecutive year, he gave his driver only one instruction as the vehicle started snaking through the labyrinth of Melbourne’s roads: be ready to change direction.

Officially designated the world’s best jockey, McDonald could have gone wherever he wanted. To Crown Casino for a night on the tiles, to the lavish after party thrown by Chinese billionaire Yuesheng Zhang’s representatives, to a quiet meal with wife Katelyn, even straight to bed after an exhausting day.

Instead, he was sending a message, which a few moments later, popped up on the phone of a young jockey who had watched on TV earlier that afternoon as McDonald urged Via Sistina to victory by the narrowest of margins, in a gripping last race at the soon-to-be redeveloped Moonee Valley.

“Hey brother, I’m over in 20. Hope that’s OK?”

“Hey James, of course it’s OK. But you realise you just won the Cox Plate an hour ago?”

McDonald indeed knew what had happened an hour ago.

But the first person he wanted to see after he left the Melbourne track was Tom Prebble, who less than two months ago, at age 23, suffered a life-changing injury due to a fall at the Warrnambool races which has left him wheelchair-bound.

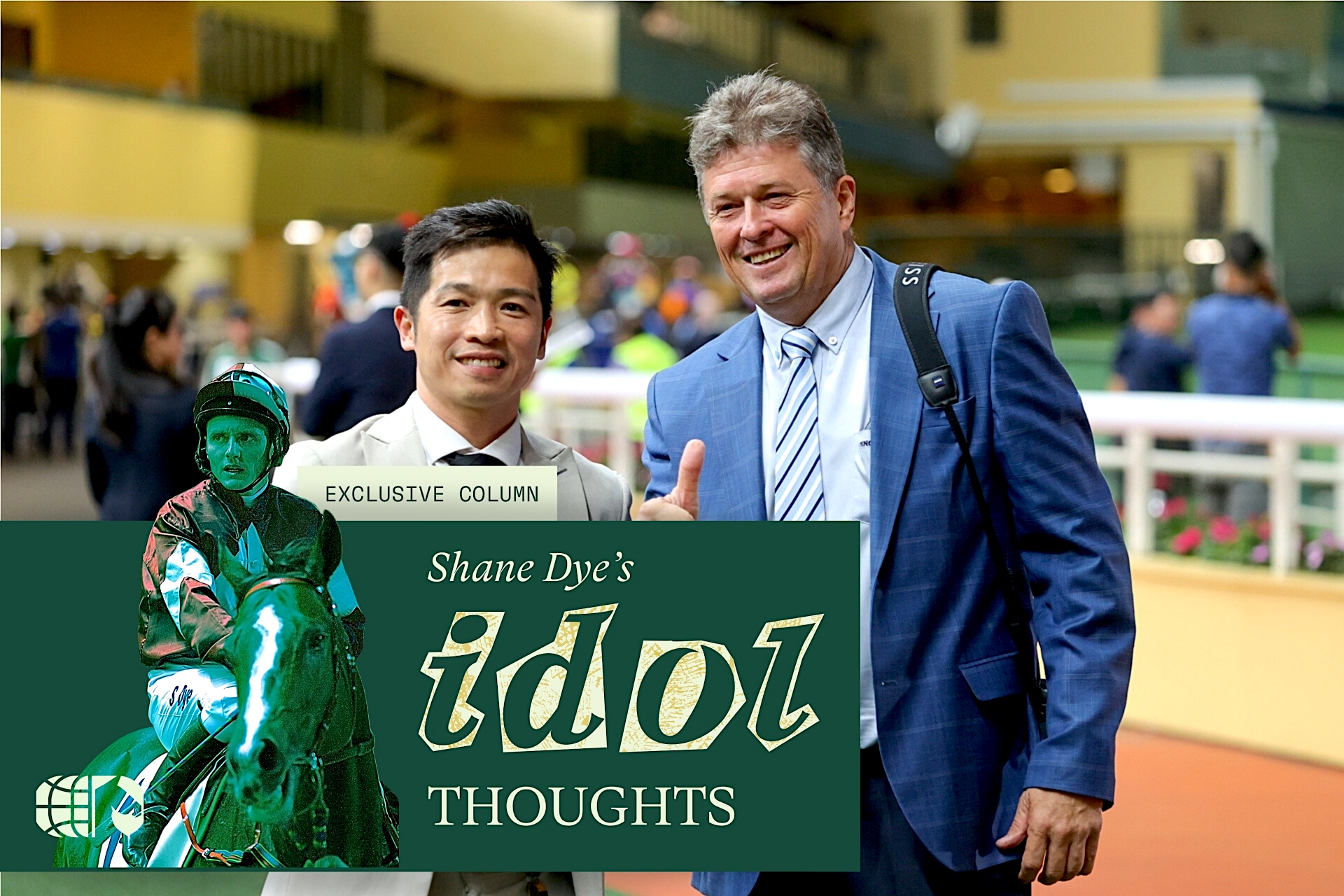

Before McDonald was the gun-for-hire in races spanning from Australia to Hong Kong, the Middle East and even Royal Ascot, he too was a young jockey.

Most people wouldn’t remember it now, but he idolised Tom’s father Brett, and when McDonald rode Fiorente to a fast-finishing second behind Brett’s Green Moon in the 2012 Melbourne Cup, the pair exchanged handshakes shortly after the finishing post. It was a beautiful moment of sportsmanship on Australian racing’s most watched stage.

When no one was watching, McDonald wanted to be there for Prebble again.

“They’re beautiful people,” Tom Prebble said of McDonald and Katelyn. “We were never lost for words. We talked about everything coming up and we spoke about me, which was nice.

“James said, ‘you’re looking fit’. I do this thing (pushing myself out of the chair) for my weight relief. I didn’t do it in front of him as a flex, but as a habit.

“He saw it and said, ‘let’s arm wrestle’. I said, ‘next time’. When I’m doing hand cycling and I’m going down to the Maribyrnong River, because I used to walk it every day, he’ll bring his bike down and we’ll race.”

It’s only a few days out from the Melbourne Cup carnival and Prebble is sitting in a café at a rehabilitation centre in Melbourne’s north-east as other patients casually wheel past and say g’day. He likes it here, mainly because it allows him to hear other people talking and interacting, a refuge from the monotony of his room and the endless noise of the call bell requesting a nurse. There’s a glimpse of the early afternoon sun, which across town is baking out the Flemington track for its upcoming four-day extravaganza he would have ordinarily hoped to have snared a ride in. Unapologetically, Prebble is wearing a pair of white crocs, the slip-on footwear popular in this part of the world. He looks down at his legs and feet, wishing there was some sensation there. He can’t feel anything.

Importantly, he knows he’s ready to talk about it now and let the horse racing industry know his prognosis.

“Now it’s been seven weeks and a day and I still haven’t improved at all,” Prebble tells Idol Horse. “Hope of a proper recovery is probably gone unless a cure is found. I’ve just got to learn to move on, I guess, and it’s a new life.

“Initially I was so upset and dirty on the world, but then I thought, ‘it could be so much worse’. I’m so fortunate in the sense I have my arms and I have my head. There are other falls where people die or have a brain injury. I’ve got everything bar my legs, and I can’t change it.”

It was supposed to be just another day at the races when Prebble, an emerging apprentice with impeccable bloodlines, travelled to the coastal town of Warrnambool in Victoria’s south-west for a mid-week meeting.

In the last race of the day, Prebble rode a horse called Pulveriser, which fell. Medics were quickly on the scene. Prebble remained conscious.

But almost immediately there was concern for his condition. He was taken to the local hospital and then swiftly airlifted to Melbourne where he underwent five-hour emergency surgery as doctors feared he’d suffered a life-altering spinal injury.

It took almost two days for Prebble to wake up after the operation in intensive care. By his side were Brett and Des O’Keeffe, a tireless jockeys’ advocate for decades who has been recognised as part of the Australia Day honours for his service to the industry.

As he regained consciousness, Prebble tried to remove his feeding tube. Doctors had to calm him. He tried to talk, but could not. Eventually, he started slowly waving his hands around to convey a message. O’Keeffe had no idea what he wanted.

“It was like trying to play a game of charades,” O’Keeffe jokes.

Brett knew exactly what he was requesting.

“I knew he wanted us to take a photo,” Brett laughs.

Told now of his bizarre request in his darkest moment, Tom smiles. He can’t remember it, and he can’t recall anything of the fall, or much of what had even happened earlier in the day. It’s just one big blur.

“I remember getting to the racecourse,” he says. “I rode two races beforehand, but I don’t remember them at all. My only memory was getting to the racecourse and unpacking my bag.

“My next memory was on the Thursday, two days after the fall when they were taking the feeding tube out of my mouth and getting the MRI scan, I was constantly choking. I guess it’s from the shock or the pain of something like that.

“Apparently, I was conscious the whole time (after the fall).”

There’s no exact science on if, how or when a spinal injury heals. But most doctors know the first 72 hours after an accident is the most crucial for determining a patient’s recovery.

When three days had passed, Prebble still had no feeling in his torso and legs. His medical team had to convey he was unlikely to be able to walk again, diagnosing him as a “complete ASIA A paraplegic at T4 level”. His spinal cord is not severed, but it’s been severely damaged resulting in paralysis of the trunk and legs.

“I’m holding out on hope,” Prebble says. “I haven’t improved at all, but they said it can take up to three months for the swelling to go down. There was a lot of swelling.

“Even just for a small sensation, I would do anything for that. There’s been a lot of research in Switzerland and Canada, I could go across there. Any options that could help me to get some sort of feeling (I’m open to). The way I see it I’ve got converted back to a toddler again, and now I’m growing and learning.”

If ever there was someone born to be a jockey, Tom Prebble would be it.

As a son of Brett Prebble, Hong Kong’s fifth most winningest jockey of all time, and Maree Payne, who rode more than 400 winners in Australia in the late 1990s, Tom was going to find his way into the saddle whether he liked it or not. But no path in life is ever truly linear, and Prebble’s pit stops along the way included studying nutrition and dabbling in real estate.

His childhood was mostly spent in the apartment blocks adjacent to Sha Tin racecourse, where his father battled the likes of Zac Purton, Douglas Whyte, Gerald Mosse and Darren Beadman on a weekly basis. Luke Ferraris, a rising superstar of the Jockey Club’s riding ranks, was a close school friend.

“I would have seen Hong Kong as my home,” Prebble says.

Brett and Maree never pushed Tom towards racing, and after he returned to Australia to finish his senior schooling, his path seemed destined to be away from horseback. It was only during the early days of the COVID pandemic when horse racing forged on as other industries shuttered that Tom started to see a future with thoroughbreds.

Armed with the knowledge of tertiary education studies in nutrition, he told his parents he would be able to counter his significant height (172cm) to keep his weight down.

“I rode for 30 years and I’d never seen a jockey with an understanding of diet at his level,” Brett says.

The winners started coming. Black Caviar’s trainer Peter Moody would often introduce Prebble to owners as “a Prebble ex Payne”. “He was bred to ride and born to ride,” Moody would say. Because of his pedigree, with each milestone Prebble would garner media mentions.

It wasn’t lost on him what each of them meant either, and they’ll live with him in permanent ink, too.

On his right forearm he has a tattoo of the Chinese symbol for “science”. His first ever winner was a horse called Scientific. There’s another etching nearby as a nod to Title Fighter, the first horse he rode to a stakes win earlier this year. Those tattoos sit alongside one of the character “No-Face” from the Japanese anime Spirited Away. Japan has always been a country which has made him feel at ease every time he’s visited.

“Dad’s not the keenest (on the tattoos), but he says I can do whatever I want now,” Tom laughs.

There was a time when, as Prebble jnr was making his way in the sport and Brett was still riding, inevitable talk of the pair competing against each other surfaced. But Brett couldn’t stomach riding against his son, and with little fanfare, closed the book on his own glittering career in early 2024.

“I rode against my father and I didn’t enjoy it,” Brett says. “I just worried about him all the time, his safety. I would have been 10 times worse (with Tom). I couldn’t have done it.”

A letter arrived at Prebble’s rehabilitation clinic from an 80-year-old stranger. It resonated with him. The man said he was a punter who “couldn’t back a winner, but knew a good horse and a good jockey when he saw one”. He said few had given him as much pleasure in recent years watching races than Prebble. “That was really, really nice,” Prebble says. “It’s been unbelievable the amount of support I’ve had.”

He’s been swamped by messages and visits from those within the industry. Former Group 1-winning jockey Chris Symons, who now runs an animal farm, popped in this week for a game of table tennis. Symons won, just. It was 11-8. At the end of the match, he even managed to sledge Prebble, who reckons ping pong might be an option for him by the time the 2032 Brisbane Paralympics are on.

There are plenty of people on his side telling him what the weeks, months and years ahead will be like.

Former jockey Tye Angland, who is wheelchair bound after a fall in Hong Kong in 2018, has been a regular sounding board. Tasmanian trackwork rider Katherine Reed was left a paraplegic after a fall. She now has three kids and has spoken to Prebble. Paralympian Emma Booth has also helped, telling Prebble about her journey to representing Australia in equestrian.

They’ve all given him hope, along with the reams of literature Payne has passed on about small advancements in science and research.

“Mum has smashed me with it,” Prebble says. “She’s very hopeful of finding something to help me. She’s sent me stories of people who have been worse off than me and improved. On the day of my fall, they released research where someone started walking again. She found that and said, ‘it can’t be a co-incidence’. It gives you a bit of hope.”

Doctors and physios have been amazed with Prebble’s improvements in his strength and functionality with daily tasks such as showering and getting into a car. He hopes to be able to move into his mother’s home within weeks while modifications are made on his own house to allow easier access in the kitchen and bathroom.

When finally home, the television will still be switched onto the races, which has remained a comfort during the first two gruelling months of his rehabilitation. He still cheers for the trainers he used to ride for, the horses he used to partner. And he’s even wondering what a life might be like having a small punt.

His psychologist has also started asking him to visualise things he wants from his future. A trip to Japan appeals most.

“If you went through my camera roll, it’s just cars, Japanese food and Akihabara,” he smiles, referencing Tokyo’s famous anime hub. “I’ve actually wanted to rent a car and drive to Mount Fuji, drive along that road because it just seemed unreal.

“I love my JDM (Japan domestic market) cars. If I could choose my own car and be able to convert it to wheelchair-accessible, it would be a JDM car. That’s the dream.”

Sometime this week, Prebble will return to the races at Flemington and see the same trainers, jockeys, owners and officials that make up a tight-knit racing community. Many might not know how to greet him. His message is simple: be positive and focus on the future. “Positive vibes are good vibes,” Brett says.

“I want to get home,” Tom says. “I want to go back to society. I’m not dirty on the industry. It was a freak accident. I don’t want people to feel sorry for me because then I feel sorry for myself. If they feel bad for me, I feel bad for myself.”

It wasn’t how he was feeling when a certain jockey carrying a Cox Plate lobbed on short notice after one of the biggest races of the year. He will never have the chance again to outride McDonald, but with Prebble the overwhelming message is one of hope: cycling by the river, trips to Japan, Paralympic ambitions, and scientific breakthroughs.

And there will always be time for that arm wrestle. ∎