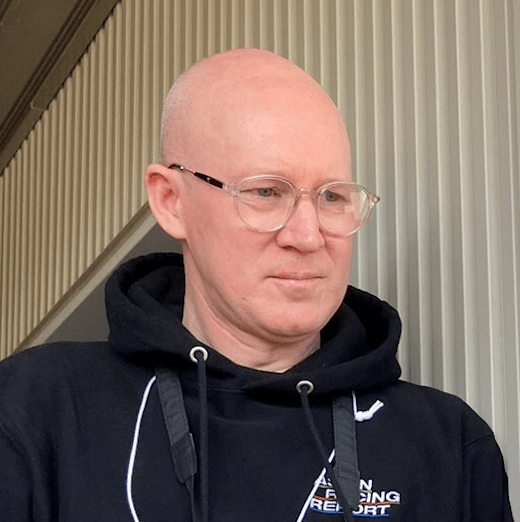

‘Beautifully Mosse’

Big-race maestro Gerald Mosse has exited the jockeys’ room to start a training career and has found a new home in Chantilly with enough room for his friendly polar bear.

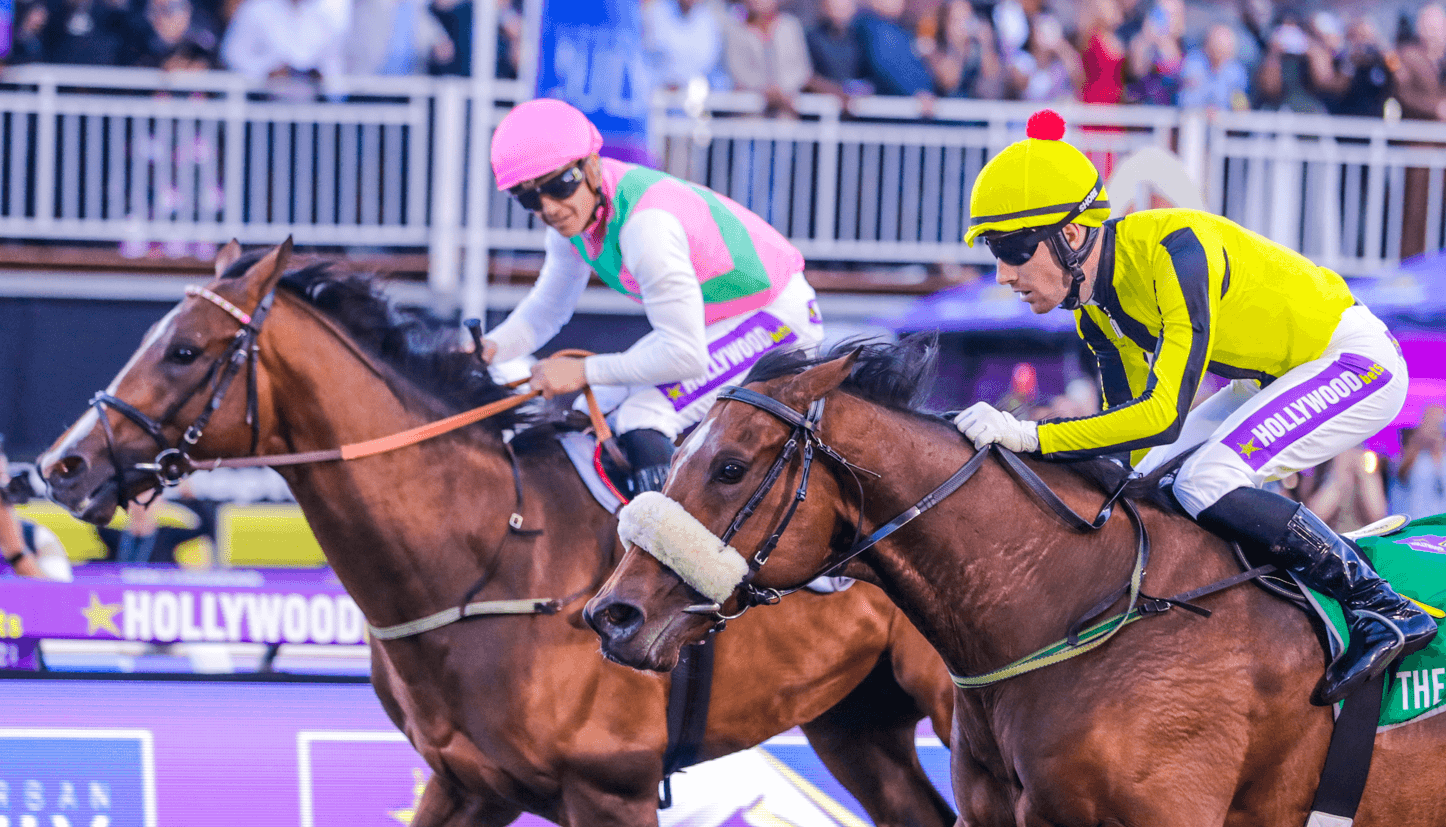

CHANCELLOR’S win in the Class 3 Lei Muk Shue Handicap at Sha Tin wouldn’t register on the radar of Gerald Mosse’s greatest triumphs: he is, after all, one of the best Group 1 jockeys the sport has known. This is the man who won the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, the Melbourne Cup, every French Classic twice or more, and the Hong Kong Cup, Mile, Sprint and Vase (times two) among a raft of majors spanning 41 years and multiple countries. But the ride was beautifully Mosse.

It was the day before Christmas Eve 2012 and Mosse’s mount was the 4.1 market second pick in a field of 11. The gelding broke sharply and the Frenchman, perched high on his balance-defying short-strapped irons, urged him forward to gain an easy three-length gap on the chasers. He kept his mount in check with a tight yet somehow light grip on the rein, his hands elevated slightly above the horse’s neck, his wrists and fingers working miniscule movements of control to guide Chancellor’s pace.

As they turned for home, Tye Angland loomed alongside on Jimson The Best, Mosse lowered into the drive and his arms started to pump. His rival went half a head in front: the pace-setter looked beaten, but the wily Mosse felt otherwise. He pulled his whip to his right hand and maintained hands and heels for a cool 16 strides: then a tap on the shoulder, five firm strikes behind and Chancellor rallied to win by a nose.

The sectionals showed Mosse had set a steady tempo, gaining an advantage while leaving something for the end. It was beautiful judgement, more so when he weighed-in 2lb overweight and was handed a HK$5,000 fine: had he been beaten, chief stipe Kim Kelly told him, his wallet would have taken a much heftier hit. Fine margins, indeed.

That race was just one example among many hundreds of Mosse’s intuitive horsemanship, his ability to understand his mount, to feel what it was telling him, and to judge and execute with tactical mastery and style.

“The horses need three things,” he says. “They need to relax, to breathe well without stress, to have no traffic jam that stops their rhythm, and then when you ask them, they will give you everything they have.”

Relying on speed maps in data-hungry Hong Kong “was not my thing,” he continues, explaining, “I always listened to my horse first, they are the ones that run. I use my brain and their muscle: I try to make them comfortable in the first part, to make sure no matter what, anywhere I’ll be in the race, they’ll be able to accelerate when they need to. I listen to my horse. Priority. Always.”

For those attributes he is renowned around the world, but he is different things to different people in different places: in Australia he gained star status with his ‘Cup’ win on Americain, but his style left many there puzzled, and his defeat on the same horse in the 2012 G1 Tancred – sitting three-wide without cover throughout –rattled their cages; in Europe, to many fans, he is still the Aga Khan’s man, the big-race maestro; and in Hong Kong he is a megastar among jockeys.

The famous horses to have succeeded under his hands is impressively long and includes the likes of Saumarez, Arazi, Sendawar, Americain, Red Cadeaux, Sacred Kingdom, River Verdon, Jim And Tonic, Ashkalani, Daylami, and Bullish Luck on whom he ended the great Silent Witness’s winning streak. The list goes on.

Southern Roots

Mosse is speaking by phone from the south of France, from a café in the general vicinity of Cannes, two days after his last ever ride as a professional jockey. He is enjoying a short break before he dives into the next chapter of his life, as a race horse trainer at his newly-renovated Le Manoir du Sanglier in Chantilly.

He is visiting family and has travelled to his lunch spot under pristine blue skies on a motor scooter. “I have a big motorbike in Paris,” he says, and goes on to extol the virtues of two-wheeled machines. “It’s an absolutely amazing feeling: it’s 35 degrees and with a fresh breeze, it’s like a dream on a motorbike or even a scooter.”

But not even that can match the bliss of riding a horse. Mosse was placed on the path to becoming one of the finest jockeys of his generation the day he was born in January 1967, the only child of Marseille-based trainer Armand Mosse and his wife Jocelyne. It was one Christmas a few years later, and some 40 years before that Sha Tin Class 3 masterclass, that his life on horseback really began.

He had asked his parents if he could have a Shetland pony for Christmas, a black and white one. His father had a runner in the Grand Steeplechase de Marseille and his parents said that if they won, they would collect the pony the following day.

“Next day we collected the pony,” he recalls. “My father said, ‘Ok, now it’s yours, you asked, jump on it.’ I cried and I didn’t want to ride because I was too scared: I was four years old. And he said to my mother ‘Ok, show him, jump on him,’ and I remember that.

“My mom rode only once, I think, and it was that time on my pony. She was wearing white trousers, like white jeans, and when she jumped on the pony, the pony ran away and she fell off into a big piece of mud. It was a disaster, and everyone was laughing … except her.

“My dad brought the pony back and put me on. I was a bit scared, but after that I rode him every single day to school. Up to 14, he lived in my house. He was like my bicycle, my motorbike, my horse; I lived close to the forest so I spent hours and hours on his back.”

From his home just outside Les Pennes-Mirabeau – his family moved there from Marseille when the training centre at nearby Calas opened to the north of the city in the 1970s – he would ride to school each day and leave his pony to graze outside with a container of water. When he was old enough, his faithful mount would take him an hour through the forest to the training centre.

A Young Apprentice

Mosse began riding for his uncle Gabriel Mosse at 14, attended jockey school for a year, and then joined the stable of his father’s old friend Pierre Biancone.

“I arrived in Chantilly at 15 and a half, normally we don’t do it like that (so young). I arrived in November and on April 2 the following year, 1983, I had my first race at Croisé-Laroche. I won on a filly called Chiquita,” he says.

Mosse is well-known for his easy, unflappable demeanour, but did novice nerves get to him when he went out for that first race ride?

“I never feel the stress, not ever, even that first race,” he says. “I had done a little bit of pony racing before so I had a little idea of what the game was, and all my life I had been with my father leading horses up at the races, so it wasn’t really a surprise.”

He was France’s champion apprentice in 1984, attached to Pierre’s son, Patrick Biancone. Things continued to roll and he attracted the attention of two French racing greats, the trainer Francois Boutin and the owner-breeder Jean-Luc Lagardere: he joined forces with them and the trio landed the 1988 G1 Prix de Diane with Resless Kara.

Two years later, at age 23. Mosse won the G1 Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe on Saumarez for trainer Nicolas Clement. When he passed the winning post in Paris, no one could have known that his upcoming flight to Hong Kong would be the start of a deep connection leading to his status as one of the city’s all-time great jockeys.

Hong Kong And Back

Mosse was following Biancone who had already made the move to Sha Tin, but it was ‘a bit complicated’ because he was still under retainer to Lagardere.

“Mr Lagardere told me, ‘You are young and talented, if you don’t make mistakes you will probably enjoy it very much,’ and he let me go, he released me. I had a really good time in Hong Kong from the beginning,” he says.

He won the 1991 Stewards’ Cup on Mastermind, and after a summer back in France riding the juvenile phenomenon Arazi, he took the same year’s Hong Kong Cup on the hero of the time, the one and only Hong Kong Triple Crown winner, River Verdon.

“I enjoyed the lifestyle in Hong Kong at that time, it was absolutely amazing,” he says. “It was a new culture, new food, and it was a new tactical way of racing for me, so I decided to focus and try to be very good there.

“When I left France I’d been winning all the big races and when you go to Hong Kong and carry on and win all the big races in Hong Kong, when you look back, you feel, wow, I’ve been lucky.”

But there is more to it than luck: there is the elite talent, the expert horsemanship, and the ability to connect with people as well.

“I’ve had to be in the right place at the right time and I’ve always put myself in the right corner at the right time,” he says. “Even if it’s luck in a photo finish, you can be lucky or unlucky or whatever, but to be there you have to prepare a little bit. So, I was going there and meeting the right people, I didn’t mix with the wrong people, I was always respectful of my boss and the Jockey Club.”

But his boss had to leave. It was 1999 and Biancone was suspended for 10 months after two of his horses failed drug tests.

“The Jockey Club begged me to stay there but I said to them it’s going to be complicated so I’d better go home,” he says.

Three titans of European racing called his phone: the Aga Khan, and the Wildenstein and Wertheimer families.

“The Aga Khan was the one who contacted me first,” Mosse says. “The Wildenstein family said they would give double the price, but I said it was not a question of money, it was a question of respect: I was approached by the Aga Khan. I’d always wanted to work for His Highness the Aga Khan, so I was delighted to be able to sign.”

Eight of his total 13 French Classic wins have been for the Aga Khan and at that time he had already enjoyed several major wins in the green silks.

More followed, notably the brilliant Sendawar’s victories in the Poule d’Essai des Poulains, the St James’s Palace Stakes, the Prix du Moulin and the Prix d’Ispahan. And Daryakana’s win in the 2009 Hong Kong Vase was classic Mosse: settling last then gathering momentum wide off the final turn for a last stride victory.

He would return to Hong Kong for short winter stints and full-season contracts up until his last contract with the Hong Kong Jockey Club in 2017. By then the respect in which he was held was cemented into the city’s racing culture.

Who else, having been suspended for 15 meetings for a contested ‘running and handling’ offence in 2015, and left off the list of licensed jockeys for the following season, would have been able to continue riding in Hong Kong? It was the weight of support from owners that enabled him to do so, getting around the system thanks to a stable jockey contract with Manfred Man.

Mosse won three Hong Kong Derbies, the first in 1994; he was the first jockey to win all four of Hong Kong’s December Group 1 races; and his record of eight wins in those Hong Kong International Races stood supreme until 2022 when Zac Purton took his tally to nine.

New Challenge, Old Friends

Mosse speaks often in the present tense when talking about his race riding and says he could ‘ride 20 horses tomorrow,’ but any future riding will be on the gallops at Chantilly. His property has a gate that opens directly onto the famous Les Aigles strip.

And he expects it to be fun. He already has some of his old weighing room peers lining up to join him of a morning.

“I’ve got a good team,” he says, “already some top riders like Dominique Beouf, (Thierry) Jarnet, (William) Mongil, (Thierry) Thulliez, they told me they will come and enjoy galloping for me, so it will be fun. All the top riders will be helping me.”

He will join them on the gallops, even if it’s aboard a pony, but for the important gallops he will certainly be holding the reins: “I’ve been all my life on a horse, I’m not going to stop,” he says.

“But even if it’s my hobby and it’s something I love to do, I think it’s time for a second life, a new challenge, a second chapter of my career. I rode for 41 years which is quite a while and I’m very happy that I’m not injured, I don’t feel pain, I’m well.”

His philosophy to training is rooted in his ‘hobby’ approach to his race-riding, meaning that while he is the utmost professional, he loves it. Now he wants to share that with the owners “So they can have a good time,” he says.

“The staff and the owners will be comfortable at the stables, as will the horses, to make sure everybody will enjoy it. It’s a bit small, but it’s an English house, and in Chantilly it’s quite cute, so I’m very lucky to be able to find it in the right location.”

Small by some measures, but there is at least room for one of his most prized possessions, his kindly-faced, stuffed polar bear, all 2.8 metres of its great height. The bear – “I always loved polar bears, he’s part of the family” – is the result of a visit long ago to an antique fair, where he encountered a taxidermist, and it has been a point of confusion at least once.

That he has a polar bear in the sitting room of his manor house speaks to his individuality, his taste and style, and to the wealth he has accrued from his stellar career. Also, to the social circle in which he moves so comfortably. He relates the time the late billionaire Alec Wildenstein gave him a call.

“I thought he was calling to offer me a ride, but he said, ‘Can I ask you something, how do you feed your polar bear? Because I have bears in Kenya and I have a problem to feed them,” Mosse recalls, his voice smiling.

“I thought, oh, he’s going to be disappointed. I told him, ‘I have a polar bear, that’s true, but unfortunately I can’t help you much because I don’t feed him, and I don’t feed him because he’s already passed away, but he’s in my living room, for sure,’ and he was laughing when he realised.”

As he finishes up with lunch, he says that being a jockey was the only thing he wanted to be from the age of three years old, and he acknowledges the huge influence of his parents in enabling the life he has had travelling the world, riding big winners, doing what he has loved since he first sat on that black and white pony and began to feel and understand the animal. But now the next ‘chapter’ begins.

“It’s time to do it now, to be a trainer before I’m too old to start,” he says. “This is what my father was, it’s where I started.”