“Never Give Up On A Horse”: Benno Yung Retires With His Head Held High

Persistence has been a constant theme of Benno Yung’s life in racing, from an apprentice that grew up in a Kowloon housing estate, to a trusted assistant that never let go of his dreams and then overcoming leukemia to retire at the top of his game. Michael Cox profiles the popular trainer on the eve of his final meeting.

“Never Give Up On A Horse”: Benno Yung Retires With His Head Held High

Persistence has been a constant theme of Benno Yung’s life in racing, from an apprentice that grew up in a Kowloon housing estate, to a trusted assistant that never let go of his dreams and then overcoming leukemia to retire at the top of his game. Michael Cox profiles the popular trainer on the eve of his final meeting.

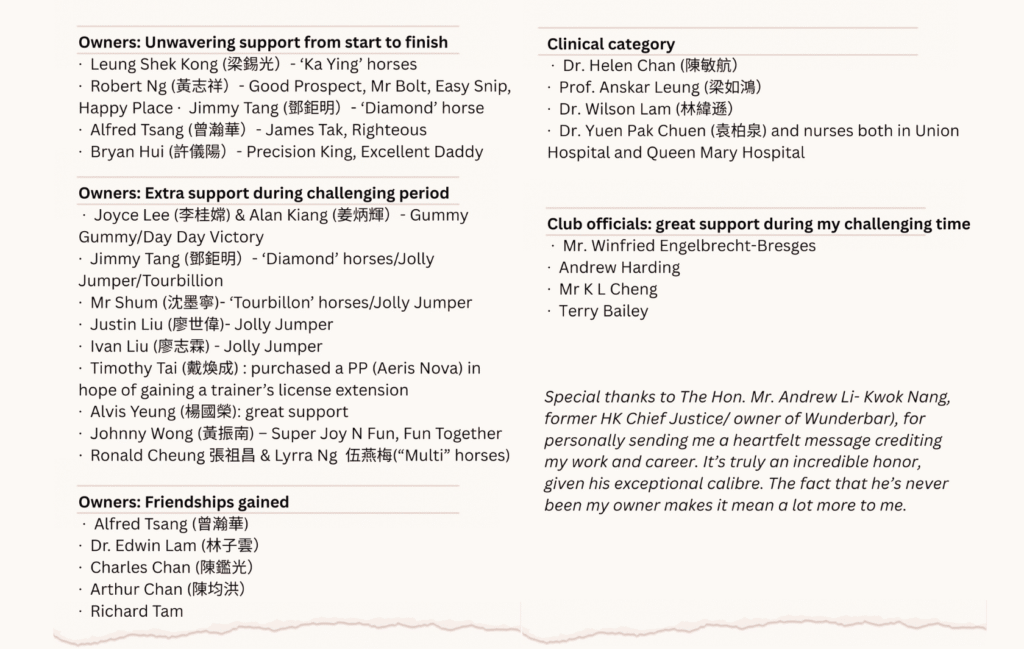

15 July, 2025IT SAYS EVERYTHING about Benno Yung’s selfless attitude to life, his horses and the sport of racing itself that the day we asked him to tell us his story – the one day he might just let it be all about him – he arrived at the Sha Tin Racecourse Clubhouse clutching a piece of paper with a long, hand-written list of people he wanted to thank.

On the list were loyal owners, Jockey Club officials, doctors and nurses. Unlike many in his profession, self-promotion isn’t a skill that comes naturally to Yung. But the list and the fact Yung took the time to make it, illustrates the type of trainer he strived to be for 12 seasons until his retirement this week, aged 66.

“When I was promoted to become a trainer I was already in my 50s, so I knew my career wasn’t going to be that long,” Yung told Idol Horse. “So I asked myself, ‘what is my goal?’ I had seen as assistant that the relationship between trainers and owners seldom lasts long – most times they break-up – so that I decided that I wanted to build real friendships. And I wanted to never give up on horses, give them every chance to be their best.”

Yung’s life in racing started about as far from the green turf of Sha Tin as one can imagine. He was born and raised in So Uk Estate, a mini-city of more than 15,000 people in 16 towers set on a hillside on the outskirts of Sham Shui Po District, Chueng Sha Wan.

So Uk Estate was home to a host of talented individuals; it is where Canto pop star Sam Hui and the brothers from the band Beyond grew up. One thing the concrete jungle did not have, unsurprisingly, was horses.

Yung was one of five children and his father – a camera salesman – watched horse racing from time-to-time, and when the annual recruitment for the Jockey Club apprentice school was announced, he suggested that his slightly-built but athletic son take a look.

It was 1976 and the apprentice school’s third intake. Yung’s classmates included current trainer Danny Shum and the gritty toughness and work ethic the two trainers share can be traced back to the discipline of those early days.

“It was pretty tough,” Yung said of school life at the Beas River campus in the New Territories at Sheng Shui. “We lived there and had one day off, Sunday, every Sunday. We lived there, ate there, we lived in the quarters with the whole team. I think at that time, you know, there were around 14 of us.”

Yung was one of the better riders but it was tough to make an impact in a culture where Chinese jockeys were derided by the media as second rate. Other than local legend Tony Cruz, star foreigners like Gary Moore dominated. These days apprentices are sent to Australia to develop their skills at regional racecourses, but in the 1970s it was a case of ‘sink or swim’ in the deep end of Hong Kong racing and opportunities were scarce for young riders.

There were still highlights for Yung. He remembers his first win on a horse called Kung Fu, in November 1979, like it was yesterday. “He led and won, Gary Moore was in the race but what I remember most was trackwork that week.”

The win was a straightforward ‘sit-and-steer’ job but a story Yung shares of a few days earlier is another example of his dogged determination to ‘not let go.”

Two days before his maiden victory Yung was unseated at trackwork. He was just out of sight of trainer Tam Man Kui and Yung gripped on tight as he was dragged though the dirt. “It took about 50 meters but I got the horse to stop and I got back on,” Yung says. “The other jockeys were saying ‘you’re crazy’ but I could not let go otherwise there is no way my boss would let me ride in the race. In those days it was very difficult to get a ride.”

By 1986 it had become so difficult that Yung set his sights on training. Through the usual progression of work rider to head lad and on to assistant, Yung spent most of his early time under the guidance of John Moore.

It wasn’t enough for Yung that he worked for one of the best in the business – albeit in Moore’s formative years – he wanted more. Each off-season Yung would pay his own way on working holidays around the world to sharpen his skills and broaden his perspective.

First it was Newmarket in England under the former Classic-winning jockey-turned trainer Frankie Durr, a tough Liverpudlian with an eye for detail and a philosophy with horses that Yung warmed to;‘The first principle in getting the best out of a horse is to be kind to it,’ was the Durr doctrine.

Yung’s annual and entirely self-funded study tours also included Australia – under the top handler Paul Sutherland at Rosehill – and North America, riding work at Canada’s Woodbine and New York’s Belmont Park.

It was on these trips that Yung was beginning to see the type of trainer he wanted to be – horse-first like Durr – and examples of the type of trainer he didn’t want to be.

“The Americans pushed those horses very, very hard. Even their two-year-olds. Every single horse had problems. There were quite a lot of two-year-olds that already had knee problems, tendon issues – they worked fast three times per week.”

Yung’s thirst for knowledge, calm demeanour and relentless work ethic saw him soon elevated to assistant, first with Christopher Cheung in 1991, then for two seasons with South African Tony Millard. Then came a life-changing meeting with a new Australian trainer named John Size.

The laconic Queenslander with a languid stride was relatively unknown and, in hindsight, an inspired choice as trainer. Yung said the same thing many were thinking when they saw Size stroll on to Sha Tin in his wide-brimmed hat and rubber boots – all he needed was a piece of straw dangling from his lip and some corks from the hat’s brim to complete the look. “He looked like a farmer,” says Yung. But it only took one conversation for Yung to be convinced he was in the presence of greatness. “After my first conversation with him I came home and told my wife and daughter ‘this guy is going to be a legend’.”

After working with Millard – a hard taskmaster on his horses and staff alike – Yung found a complete contrast in Size, who did everything at a slow and mindful pace.

“You can see for yourself the difference between them, just look at the records. Tony was quite aggressive, but John was patient and it was championship, championship, championship,” Yung says, referring to the stunning hat trick of titles that kickstarted the trainer’s career.

“John had a style where the foundation of fitness was built up slowly and the horse lasted longer. The most important thing to John was the horse and you could see how they kept running on and improving.”

In Size, Yung had met a man who matched his ‘first to work, last to leave’ work ethic and carried the same care for horses. “It was just full dedication,” Yung says. “He would mix feed himself and ride track work himself. It was simple and straightforward, but he worked hard.”

Early on, not everybody was convinced about Size – one trackwork rider quit the stable, citing the trainer’s unconventional methods – by the end of that season though, Size had surged to a championship.

“He made a lot of people look bad. He was taking transfers and just turning them around, from Class 5 to Class 1, ” Yung says, recalling that even the late, great Ivan Allan – a hard man to impress – had admired Size. “Even Ivan, he talked to me one day, he said, ‘your boss is the one I pay the most respect to of all the trainers here’.”

Yung was with Size for 12 seasons – seven of them championships – but as his own ambition grew, he was denied a trainer’s licence. Yung lost count how many times he had applied “At least ten,” he says.

He was 54 by the time he was finally licensed ahead of the 2013/14 season and by then he had a strong idea of the type of trainer he wanted to be.

First of all, he says, he had his own mantra: “never give up on any horse” but he could also see that there was a price to pay for success in Hong Kong racing.

For top trainers – even Size – there is a ruthless aspect to staying at the top: underperforming horses have to be transferred or retired to make way for new stock. Sometimes the choice is as simple as winning races or making friends.

“I didn’t want to just kick out horses directly because the price to pay would be losing those friendships,” Yung said.

The long list in Yung’s hand is evidence that he stuck to his word. As is the nickname from local press 容大夫 – “Dr Yung” – thus named for his efforts at patching up and persisting with problem horses.

Maybe because of that philosophy, Yung never had a superstar but his record of 368 wins in 11 seasons was marked by consistency. Perhaps the statistic that is testament to Yung’s owner-centric, horse-first ethos though is that he still has 41 horses on his books just days before his stable shuts for good. That owners are willing to leave their horses with a trainer due to retire in a matter of days speaks volumes of the trust he has engendered with owners.

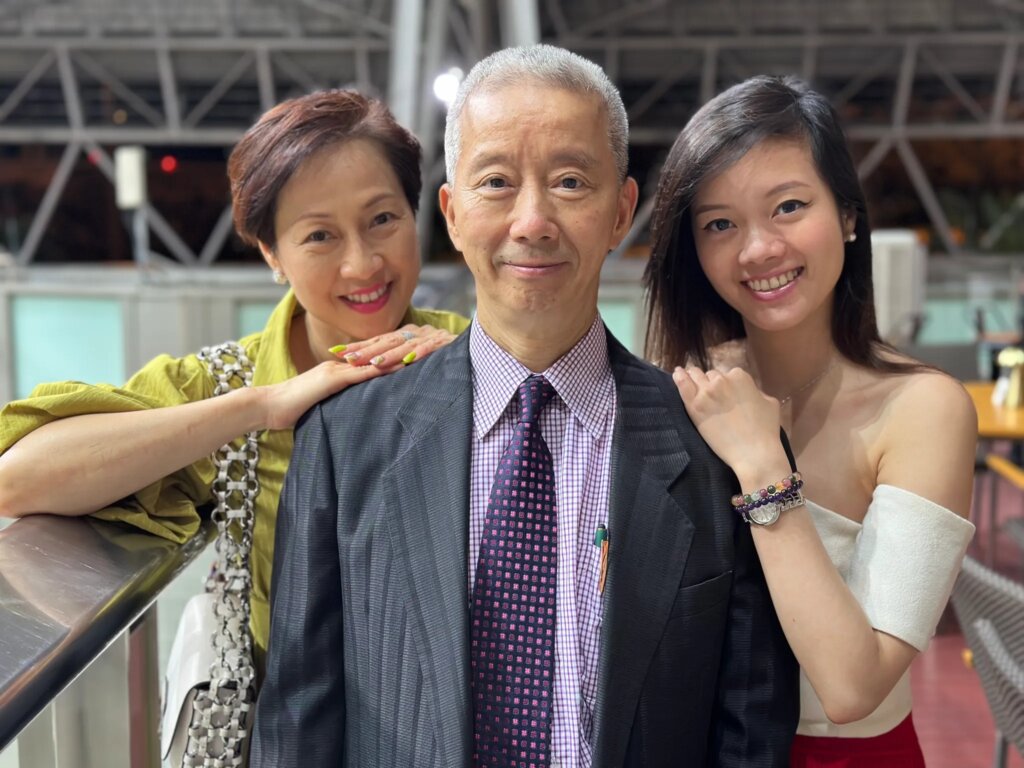

Of course Yung’s final season will be remembered for far more than his on-track record. In June 2024, Yung was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). He strived to work everyday from home, even during treatment. Following a bone marrow transplant from daughter Sam and successful treatment, he made a welcome return to the races in December.

To that point Yung’s stable had struggled to one winner from 106 runners. Since then Yung has won 19 races, each one of them celebrated like a Group 1.

As our conversation comes to a close, Yung still wants to talk about his list of people to thank. When it comes time to mention his family, though, there is an emotional pause and the words are succinct. “My everything,” Yung says of wife Phoebe and daughter Sam.

From the moment he walked into the jockey school nearly five decades ago to now, Yung’s life has been dedicated to horses and their owners. What now that the alarm won’t need to sound before 4am?

Yung isn’t sure exactly what he will do, but he won’t be lost to racing – bloodstock consultancy with Sam is an option – but one thing is certain, part of his life will be dedicated to helping others. Also on Yung’s hand-written gratitude list are professors, doctors and nurses – and one of the first things Yung did once he finished his treatment was make a donation to the Union and Queen Mary Hospitals.

“Hopefully I can use my specialty, horse racing, to help those less fortunate,” Yung says. “I hope I can find some way to use horse racing and help me make a contribution to the whole society, the whole community, I’ve been helped by people so I hope maybe one day I give something back.” ∎