From FBI To Stay Inside, Michael Freedman’s Full-Circle Racing Life

He grew up in the shadow of greatness at Flemington – then chased his own story across Asia and home again.

From FBI To Stay Inside, Michael Freedman’s Full-Circle Racing Life

He grew up in the shadow of greatness at Flemington – then chased his own story across Asia and home again.

11 February, 2026THE HOUSE is long gone and the stables are just a memory for those lucky enough to work in the tiny yard behind Flemington at Leonard Crescent, but there was a time when horse racing’s version of The Beatles were just out the back in the stables.

In front of you, Super Impose. To the left, Schilacci. To the right, Mahogany. Over there, Subzero. Behind, Mannerism. If you could have made them walk across a pedestrian crossing in unison near Lee Freedman’s house, it would have been another instantly iconic photo.

In the early 1990s, horse racing in Australia was cool. It always had a mystique about it, but perhaps it has never been so popular. Tommy Smith had been at the top for a long time. You knew there was a chance Bart Cummings would be delivering a deadpan one-liner on the first Tuesday in November. Colin Hayes had handed the reins to his trailblazing son David. Jockeys such as Darren Beadman, Shane Dye and Mick Dittman were household names.

But what made it really cool was the Freedman brothers.

With their sharp suits and Ray Ban sunglasses and an ambition only limited by their imagination, brothers Lee, Richard, Anthony and Michael were the new kids on the block. Lee was the eldest of the quartet and the name in the racebook before training partnerships were a thing. He had long been the family’s north star after father, Tony, died when he was just 55. Lee was still in his 20s.

The brothers were cleverly coined as FBI: Freedman Brothers Incorporated. It stuck. Hordes of new fans were introduced, or attracted, to the sport because of the flashy siblings making Australian racing sexy. It seemed every other week, FBI were winning major races around the country.

The youngest brother, Michael, walked around Lee’s base not only in awe of his eldest brother, but the horses he was tending to.

“Probably at the time, we didn’t appreciate how lucky we were to have the quality and calibre of horses around us,” says Michael Freedman.

“There were 14 boxes out the back of (Lee’s) house at Flemington. At one point there were 12 Group 1 winners there. You look now, and you’re happy to have one or two Group 1 standard horses in your stable.

“It was the who’s who of Australian racing.”

Still to this day, many good judges maintain the best Cox Plate ever run was in 1992 when the Freedman brothers saddled up even-money favourite Naturalism and Super Impose against a field featuring Japan Cup winner Better Loosen Up, Let’s Elope, Rough Habit and co. Thirteen of the 14 were Group 1 winners.

Down the side of the old Moonee Valley circuit as the pack bunched, Naturalism fell as part of a chain reaction and launched Dittman into the air. It was described as a “trainwreck on turf”. As the crowd collectively held its breath, Let’s Elope circled the frontrunners and burst to the front in the short straight. While the Freedman brothers fretted over Naturalism and Dittman lying on the turf, their other old great warrior, Super Impose, charged from back in the field and nabbed Cummings’ great mare on the line. The Cox Plate has long been dubbed the “greatest two minutes in sport”, but it had never been so dramatic.

“In my mind, that still remains the greatest Cox Plate of all time,” Michael says.

From Flemington to Caulfield and then down to the Mornington Peninsula near Melbourne, the Freedman brothers cycled through different homes for their horses, but kept winning major Australian races for almost the next two decades.

They probably never had a greater horse than Makybe Diva, the mighty mare who won three Melbourne Cups, the latter two under Lee Freedman after David Hall moved to Hong Kong. After she lumped a record weight to a historic treble in 2005, Lee Freedman delivered the great line: “Go and find the youngest child here, as that child might be the only person who lives long enough to see something like this again.”

He was right.

No horse has ever defended a Melbourne Cup since, let alone threatened to win it three times.

As is the way with families, it wasn’t long after the band started to break up. FBI had spent decades climbing to the top of the mountain, but their paths needed to diverge. All are still involved to this day. Once horse racing is in the blood, it rarely leaves.

Anthony is the most reclusive, now training with son Sam, aided by the long-time imprimatur of Godolphin meaning they’re still regular players on the big stage. The outgoing Richard has walked a winding path through media and even race club administration, but is back doing what a Freedman is meant to do: conditioning racehorses. He does it with son Will.

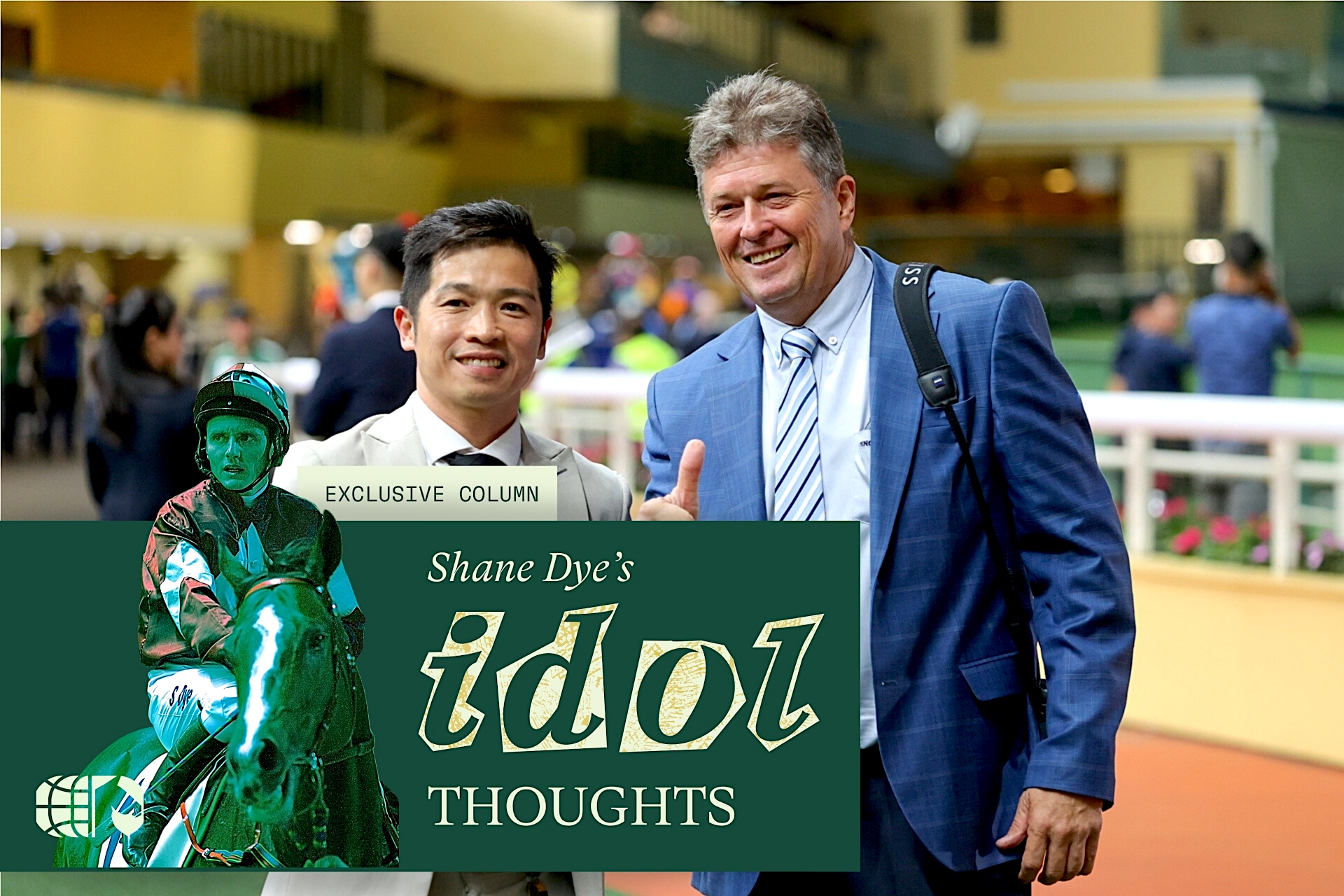

But perhaps none have had a more fascinating career arc than Michael, whose full circle moment came recently when he employed Lee to work for him. The Hall of Fame conditioner now runs Michael’s Gold Coast satellite stable, where he can bury himself in the puzzle of horses and not the paperwork of running a business.

From a successful stint in Singapore to an ill-fated one in Hong Kong mired by a freak accident with a horse walking machine and the highs of Golden Slipper victories, Michael’s profession has ridden highs and emerged from lows.

But no challenge was bigger than a personal one.

“Oh, you’re not having two. You’re having three.”

It only took a few words from a doctor for Michael and wife Anna Freedman’s life to be turned upside down. Michael had already rushed back from Sydney during the Easter carnival to be at pregnant Anna’s side for an important scan. They thought they were having twins, but never did they imagine there was a third baby on the way.

“I thought it was great, three kids at once and I was high fiving,” Michael laughs. “Anna was nearly in tears. She had a lot better understanding of what we were in for. It was life changing to say the least.”

A mother’s instinct is almost always right, and Anna was no exception. She gave birth to triplets – Max, Sophie and Jessica – at 29 weeks, more than two months before a normal pregnancy period. Between the three of them, they weighed less than three kilograms. Max was the tiniest at just 900 grams.

Anna never had the chance to hold or barely see the kids, doctors and nurses whisking them off to intensive care immediately after the birth. The Freedmans were warned there could be complications for the kids being born so prematurely, from hearing or sight loss to a multitude of other problems.

It took three months, but eventually Max, Sophie and Jessica were allowed to leave hospital.

“Once they came out, occasionally we had them stop breathing (needing urgent medical treatment),” Michael says. “It was a pretty stressful time.

“I had a very capable wife, and we had great help from family and a couple of night nurses who would come in throughout the week. People always ask, ‘how did you do it?’ But what was the alternative?”

The kids wouldn’t be old enough to remember it, but it was shortly after Makybe Diva wrote herself into Australian racing folklore, but everyone involved with FBI knew the glory days were coming to an end.

By 2008, Michael was ready to go out on his own as a trainer … in Singapore.

“Anyone in a large family would say you have your moments from time to time,” Michael says. “But we always managed to work it out. It worked very well for the best part of 20-odd years. For any partnership to last that long, be it family or not, is pretty good.

“But we all grew to an age where we wanted a bit more space and to do our own stuff. There was probably no better way for me to go out on my own than in a completely new jurisdiction (rather) than putting my own shopfront here in Australia, be it Melbourne or Sydney.”

Anna agreed to the leap of faith to move the family to Singapore, and Michael quickly made an impression among the racing fraternity, which included a strong expatriate Australian and New Zealand flavour.

The kids thrived, attending various international schools and making friends they have kept to this day. So diverse was the culture, at one stage Michael and Anna sent Max, Sophie and Jessica to school in Malaysia, where they would commute daily.

“They would have to take their passport every day,” he jokes.

But as they approached their final years of schooling, the parents yearned for their children to finish their high school days in Australia, so they came home.

It didn’t last long. Sitting on his lounge one Sunday afternoon, Freedman received an unexpected call from a high-ranking Hong Kong Jockey Club official. Did he want a coveted spot on the Club’s training roster?

“I did have an itch I needed to scratch,” he says.

He said yes.

No racing environment in the world is more fanatical and fickle than Hong Kong. New players – be it trainers or jockeys – need to make a fast start to get owners and punters onside.

Freedman hadn’t even had a runner when a freak stable accident doomed his Hong Kong career before it had started. A partition on a stable walker became jammed on a horse’s back. It caused a glitch on the machine. A horse galloped in the wrong direction, horses were suddenly taking fright and essentially controlling the speed of the apparatus. Frantic efforts to stop the machine failed. Even the emergency button was disabled.

One horse had to be put down. Eight others were injured. In his own words, Freedman was a “dead man walking” after that.

“That was probably a chapter in my life I can put behind me,” Freedman says. “I chalk it up to experience. I didn’t really like living there much for a lot of reasons – we left the kids back here at boarding school – and I think by then I was a bit (tired of living in Asia).

“I found it very claustrophobic and everyone you were competing with or against is right in your face. I’ve always tried to maintain a good lifestyle outside of racing. I found it very difficult in that environment. We made the decision to come back – and I haven’t regretted it for one minute.”

If there were prizes for the best-named horses, then Michael Freedman would have one near the top of the pops.

Stay Inside, which he prepared with brother Richard before they abandoned their training union, was given the moniker during the heady days of the COVID pandemic. It seemed all of Australia was perpetually in lockdowns to grapple with the virus, so it was appropriate a horse emerged as a star befitting of the times.

Just as the country needed a pick-me-up, so too did Michael after the Hong Kong debacle. And the two-year-old colt delivered on early promise to win the Golden Slipper for Michael and Richard Freedman in 2021. It’s the world’s richest juvenile race and has long been a major influence on the country’s breeding industry. Michael had reminded everyone in Australia how good he was as a trainer, and particularly with two-year-olds.

“It was amazing timing to bob up when he did,” he says of Stay Inside. “I think I’d come back from Hong Kong 18 months before that. It gave me the ability to kick on from there.”

While Michael and Richard’s training partnership ended, the winners have continued to flow.

Last year, he won the Golden Slipper again – this time solely in his name – when Marhoona burst to victory at just her third start. The filly will line up in this Saturday’s G1 Lightning Stakes at Flemington.

So, does Freedman like the tag of being a premier two-year-old trainer?

“I’m not complaining, don’t get me wrong, but I do think I’ve trained some other good three-year-olds to win races,” he says. “You hope you don’t get pigeonholed too much. I don’t get offered many older horses to train, but conversely I do get good support at the sales. It does get frustrating sometimes, but I’m not complaining.”

It speaks to Freedman’s desire to challenge the norms. He has written down a list of rules he thinks should be tweaked in racing to make it a better and fairer spectacle.

Top of his list is the use of more technology to help stewards make informed protest decisions, a la the resources given to remote officials in other sports such as cricket, football and rugby league.

His views have only emboldened after Ninja was denied winning the Magic Millions Guineas on the Gold Coast after a controversial protest. If stewards had horse tracking technology, Freedman argues, which told them exactly how much ground a horse is making on another before interference, their decision wouldn’t be so subjective.

He has also proposed trainers be allowed to finalise gear changes after barrier draws, typically 12pm on a Wednesday for a Saturday meeting in Sydney.

“I might put blinkers on a horse, but draw 15 of 15 and then don’t want blinkers because it won’t suit,” Michael says. “How come we can’t wait until midday when we have to nominate a jockey to make a gear change and be able to evaluate where it’s drawn and may end up in the run?”

It’s a fair point, and one he can press with Lee during their regular phone calls as the master now works for his one-time apprentice.

Not far from Lee, Sophie is working for the Gold Coast Suns in the Australian Football League, a far cry from the tiny baby who had to spend three months in hospital. Max is in the final throes of becoming a qualified vet and Jessica works in interior architecture. They all graduated from university. Much like the Freedman brothers eventually did themselves, they’ve all found their own, and different, paths.

“From a young age, Lee taught me everything I know,” Michael says. “I remember having a chat to him (as a teenager) saying, ‘this is what I want to do’.”

The thing about bands – even the great ones – is they don’t stay together forever. They splinter, regroup, tour under different names.

The house at Leonard Crescent is long gone now. The stables are a memory for the lucky few who saw it up close. But the imprint remains – a time when Australian racing had household names, and the Freedmans were its sharp-suited frontmen.

Michael has kept going: Singapore, Hong Kong, back home, back to winners – once racing is in the blood, it rarely leaves.

He’s glad he lived through the coolest era the sport ever had … Ray-Bans and all. ∎