A pied wagtail flitted from the edge of platform six down onto the metal rail at East Croydon station. A group of about 30 children, rain coats zipped against the damp wind, their backpacks hung with dangling toys, pointed and chattered delightedly at the little bird as it bobbed its long tail and flew off. Perhaps they were going to Epsom, too?

The 10:10 to East Grinstead pulled in. A pigeon the group had turned its innocent attention to winged away in front of the decelerating train and several children waved and shouted “Bye, bye.” They were shepherded into line and entered the carriage. No Derby for those kids, not this year.

The Tattenham Corner train arrived soon after and a handful of people boarded, average age being a number in the high 40s, perhaps: two thirty-something men, smart blue-suited and rain-coated, talked about the races, one explaining to the other the workings of apprentice claims.

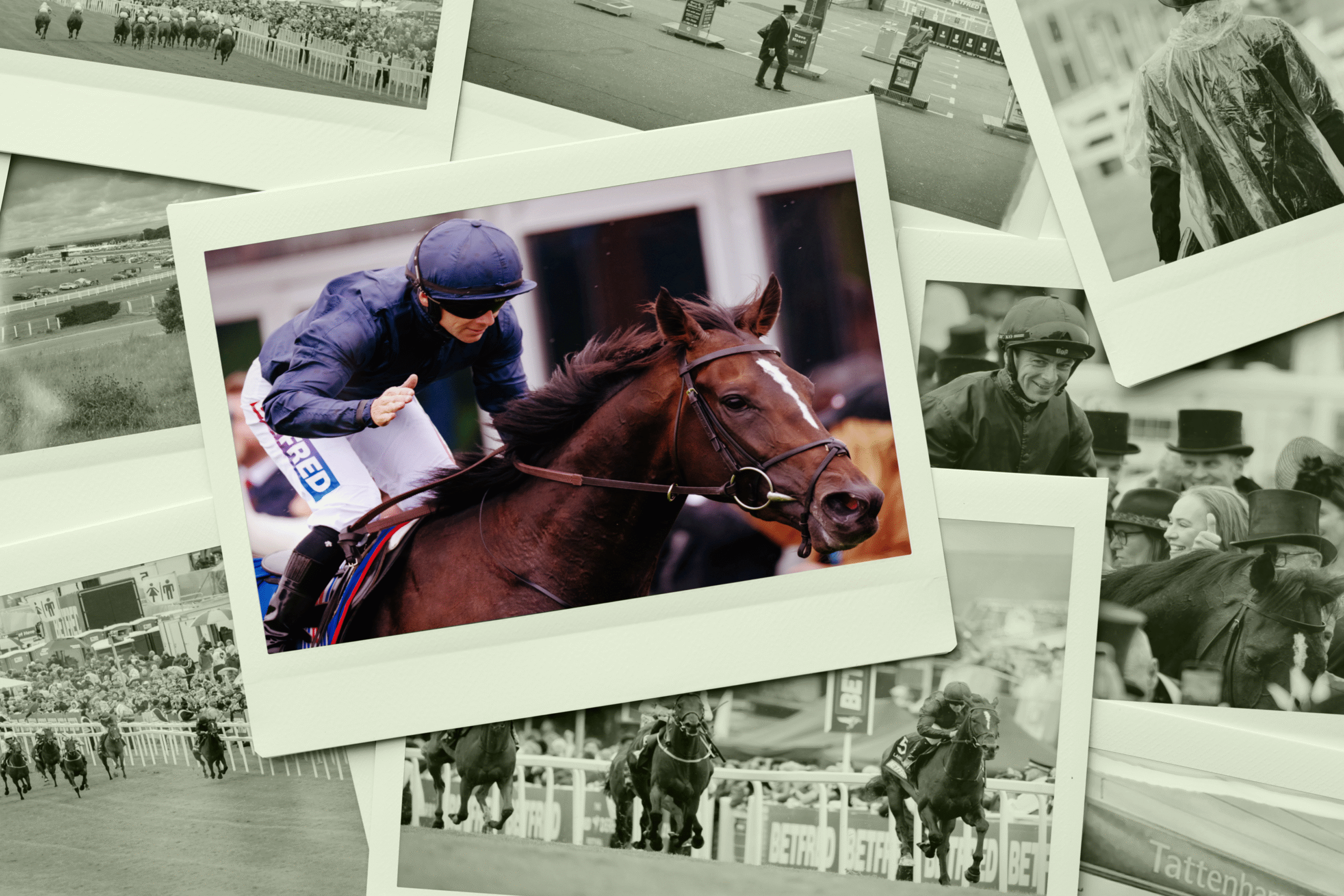

When it reached its destination 35 minutes later, each of the eight carriages dripped out seven, nine, or a dozen Derby-bound travellers, no more. Trade must have been slack for the handful of ticket touts waiting at the station exit: the heyday of many tens of thousands descending on the downs felt decades distant yet for all that, it was Derby day, and the action on the track is always special on Derby day.

Epsom’s famous downs roll downhill from Tattenham Corner station across a falling and rising expanse within the course rails, known as ‘The Hill’. There the annual fairground was blasting out music, bass heavy: arena rock band Journey’s feelgood 1981 hit Don’t Stop Believin’ was soaring on the blustering wind as if battling against the threat of the lowering clouds.

The promised rain was a concern not just for the fun-seekers and the Epsom executive conscious of the impact on its paying attendance – an alarmingly sparse 22,312 – but also team Godolphin.

It was 1:52pm when the boys in blue stopped believing. The rain had not yet arrived beyond the odd brief shower, but an official announcement declared Ruling Court a non-runner due to the going, listed as good (good to soft in places) but destined to worsen. A flat atmosphere felt flatter: even the youth choir drafted in to sing the national anthem couldn’t lift it – there wasn’t a ‘royal’ in sight.

The absence of Godolphin’s 2,000 Guineas winner was a blow to Britain’s biggest race and the reason seemed odd, given that the contest has always been set up as a tough test designed to determine a horse’s durability, balance, speed and stamina – whatever the going – with a view to making a stallion.

But that was of little concern to Wayne Lordan. To be fair to Godolphin, it is hard to picture a scenario in which Ruling Court would have swept past Lordan on the front-running Lambourn: if he had, the Guineas hero would have been a colt from the extraordinary bracket; we’ll never know.

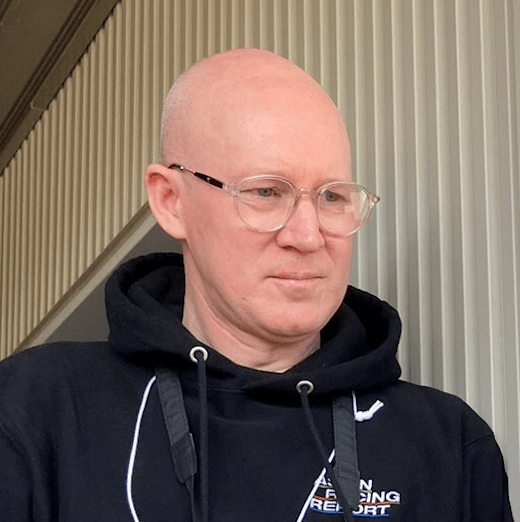

Lordan, 43, has long been the man left to pick up the best of the O’Brien-trained rest after Ryan Moore has made his selection in a major, but every now and then one falls his way. Things had gone Moore’s way in the G1 Oaks the previous afternoon when he rode Minnie Hauk, beating Lordan’s mount Whirl in a close tussle.

This time Moore sided with Delacroix, the race favourite, a decision O’Brien said was “very difficult for Ryan,” but Lordan was happy enough with that even though the market had Lambourn as the third pick for the stable, with The Lion In Winter the public’s second choice.

“I knew there were two horses Wayne wanted to ride and that’s the filly (Whirl) and the colt (Lambourn),” O’Brien said. “He won’t tell you that but those were the two he wanted to ride, and I knew that.

“Everyone latched on to the other two horses (in the Derby) but Lambourn was third or fourth or fifth favourite, wasn’t he? The word in our place was whatever Ryan wanted to ride, I knew what Wayne wanted to ride. When I’d be going round the yards in the evening, the lads would be telling me what was going on, so I knew what Wayne wanted to ride, so it made it easier for me.”

O’Brien now has an incredible 11 Derby wins to match 11 Oaks wins, and for the Ballydoyle team and its Coolmore backers, Epsom at the beginning of June remains the sport’s pinnacle, the primary focus just as it was in its early 20th century Edwardian pomp when the top hat and morning suit, still de rigeur around the winner’s circle today, wasn’t so archaic.

“Every piece of work around Ballydoyle is done left-handed … they go around Tattenham Corner,” O’Brien said earnestly, describing the Epsom replica first laid down decades ago in the Tipperary countryside by his predecessor at the legendary training base, the great Vincent O’Brien.

“The Derby is the ultimate test, the track here at Epsom it has to be like that to test them,” he continued, and the passion for the race, the original and greatest of all Derbies, was ripe in his voice.

“From December of their two-year-old career everything is going left (at home), even the sprinters, so everything they do they’re preparing for the ultimate test from the time they start.”

The ultimate test might have fallen down the pecking order among the wider British public’s sporting priorities – even among racing’s marketers – and is evidently in need of a significant profile boost, but out on the track, the horses and their riders provided a sporting spectacle befitting the Derby’s rich heritage.

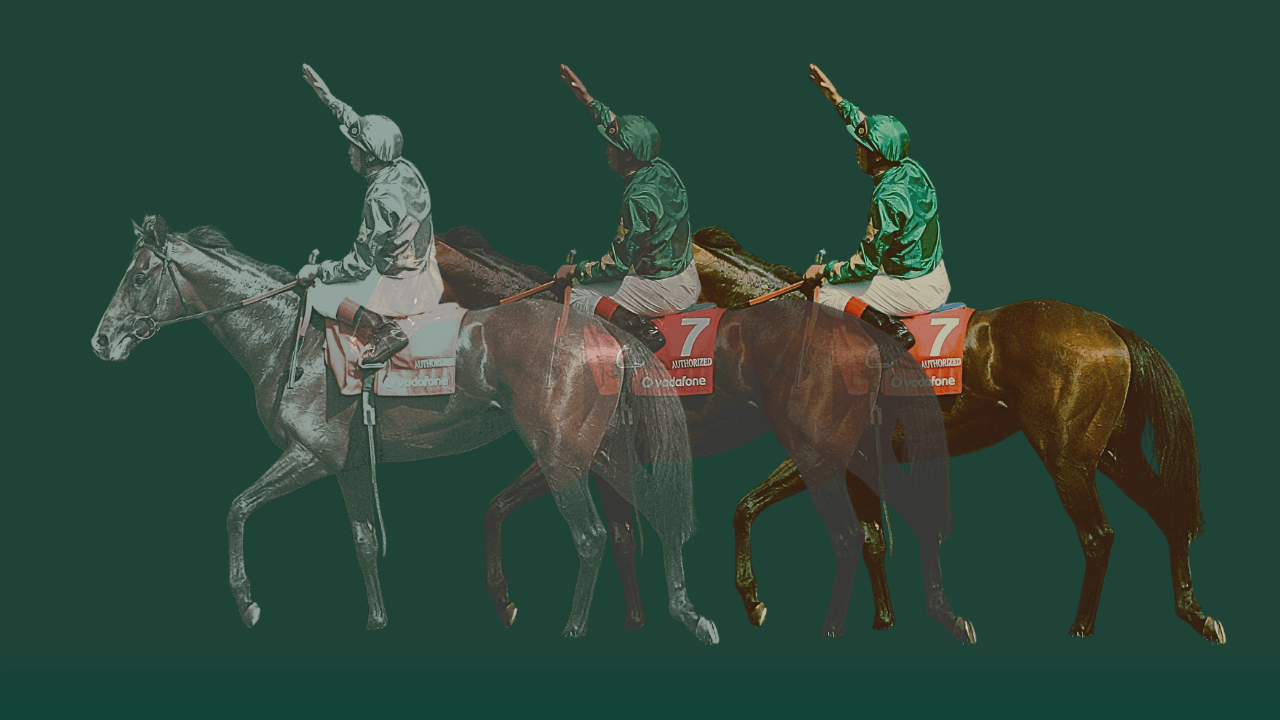

Lordan had no hesitation in taking Lambourn to the front and the Chester Vase winner seemed in control. With the field of 18 chasing, Lordan’s mount scooted downhill from Tattenham Corner and extended through the steeply cambered, rising home straight.

“I just wanted to see the three pole to get going on him, because I knew that whatever was going to get by me would have to deserve to get by me and stay,” Lordan said.

Lazy Griff, second to Lambourn at Chester, gave chase under Christophe Soumillon, but the 50-1 longshot could do no better than second again – three and three-quarter lengths behind – much to the delight of his Middleham Park Racing syndicate members and trainer Charlie Johnston.

The owners were talking German Derby, Johnston was aiming higher: Irish Derby or Grand Prix de Paris, perhaps, he said.

Trainer Joseph O’Brien, son of Aidan and a Derby-winning jockey for his father in his time, had the third, Tennessee Stud at 28-1 under Dylan Browne McMonagle.

“Wayne won a Breeders’ Cup race for Joseph,” O’Brien senior reminded everyone afterwards when praising the jockey’s achievements and his vital role within the broader team.

As far as O’Brien was concerned, the day belonged to all his people and to Lordan who spoke with smiling warmth and understated wit in the aftermath, pulled from one interview to the next. As O’Brien noted, the seasoned jockey had ridden Group 1 winners before, but Lordan was sure this win was the best of them all.

“This is a very special race to win,” he said. “When you get into racing this is the race you always want to ride in.”

And there was weight to those words in victory, given that Lordan was out for eight months after a serious fall in the 2023 G1 Irish Derby that left him with fractures to his legs and elbow.

“It’s a tough game, a lot of lads go through it, and I was the lucky one to get back,” he said.

The sky darkened and the rain began to hammer the downs as Lordan was freed from his media obligations and returned to the jockeys’ room. By the time the next race came around, the already thin crowd was leaving and the fairground rides on ‘The Hill’ were spinning round with empty seats.

The walk back to Tattenham Corner Station passed bare ground where once deckchairs and awnings would have pitched, and solitary bookmakers. On the inside of the track, between the one and the two-furlong poles, Glyn Jones was huddled close to his pitch, collar popped up against the drenching weather.

“I’ve taken less than a hundred (pounds) in bets on every race except the Derby,” the bookie said. “It’s hardly been worth it, but the weather was expected and that keeps people away: we’ve made a small profit at least.

“But,” he added, “it’s been getting worse here for a few years now.”

There wasn’t even a line of people at Tattenham Corner Station like in the old days, so no need for the snaking control barriers that had been positioned. The 17:12 train back to London Bridge was comfortably occupied at about two-thirds full, with chirpy racegoers buoyant despite being soaked to the skin.

Jack, three years old, was with mum and dad. On the table before him were the spoils of his day at the races, a pack of what looked like toy animals, or dinosaurs, perhaps – most kids have a natural fascination with birds and animals, you know – and his winnings.

“He won £15,” Jack’s mum said as the youngster spoke gleefully about his day watching the horses race.

Lordan wasn’t the only one who’d had a Derby day to remember. ∎