From The ‘Bool To The Big Time: Inside The Ciaron Maher Racing Juggernaut

Ciaron Maher’s rise from a rural dairy farm to become Australia’s most prolific trainer is a story of scale, science and self-belief.

CIARON MAHER is speeding around his lavish training metropolis for a tour he almost forgot he had to take, when he stops a little longer than usual at a back paddock.

He winds the front car windows down just enough to point out what he needs to, and given the driving rain on a misty day, you almost want him to finish talking so you stop getting wet in the passenger seat.

The focus of his attention in the faraway corner of this racehorse manor is not any of his recent and former champion thoroughbreds, but cattle. Yes, a bunch of cattle he tends to, taking just as much pride in their appearance as the horses which earn him millions on the track.

It’s a nod to his days as a child growing up on his father’s Victorian dairy farm, where he would sometimes deliver two or three calves per morning as a kid. He would then put on his backpack and head to school.

“We were making decisions at a young age with animals. You were there doing it yourself,” Maher says.

“I do think about it every now and then. All of that when you look back, it’s just reading animals I suppose.”

Maher says all this after reeling off everything a horse trainer could ever want at his pristine training property in the NSW Southern Highlands, 90 minutes from Sydney’s CBD. The term horse heaven gets thrown around far too often, but in the case of his Bong Bong property, it’s apt.

Maher points out the two 1200-metre gallops with slight uphill finishes, one grass and the other sand. He can hold private jump outs on the estate. There are two indoor arenas for his horses to use. Grand barns with several storeys-high ceilings, filled with large and lavish stalls for the horses (a minor frustration for Maher, who argues he could have more horses on site if the boxes were smaller). The main stables are attached to a magnificent auditorium and office complex, where the property’s former owner, longtime breeder Paul Fudge, would ask his horses to be paraded due to his ailing health. Racing NSW bought the property from Fudge several years ago and courted Maher to ramp up his presence in NSW by giving him the keys to the Bong Bong castle.

But what excites Maher most is the science.

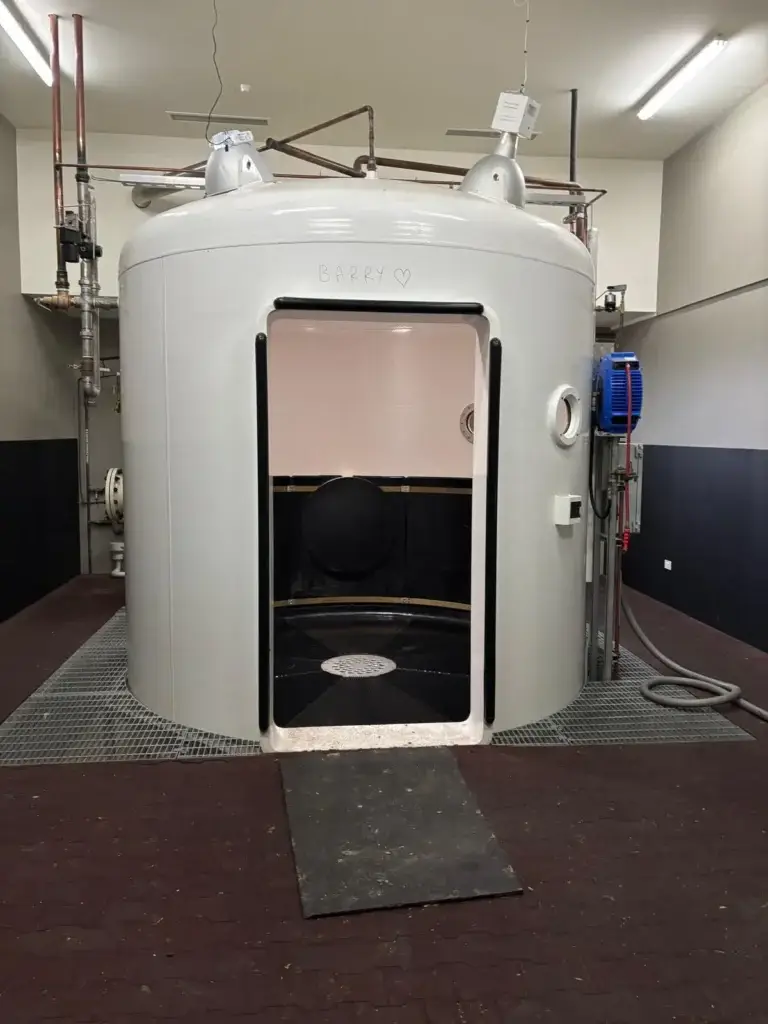

There’s a hypoxic and hyperbaric chamber, each designed to keep Australia’s most ambitious horse trainer on the cutting edge of his craft. He treats his animals like coaches treat elite athletes, boasting a dedicated sports science component of his business (his staff even publish a podcast interviewing experts from around the world).

The group monitor everything they can about Maher’s horses: heart rates, stride lengths during a gallop, stride frequencies, lactate levels, you name it, they’ve thought about it. They communicate via a sophisticated online system which shares the data, benchmarking it against the individual horse for up to years during their career. Maher buries himself in the detail each day, not able to physically watch his enormous team of horses work at any one of his six training centres each morning. Is the horse stretching out in its work as it should? Is there a problem with it? Is it recovering fast enough?

“Horses have been trained one way for a very, very long time,” Maher says. “Not coming from a racing background, I’ve always questioned why. There is no right or wrong way. Well, there are wrong ways. It intrigues me, that side of it.

“I know we’re only just scratching the surface at the moment. We have all that IP now. You start using it. With AI, it’s going to be very interesting, the next couple of years.”

Has he started planning on using artificial intelligence to help his horse training?

“I’ve started looking into it,” he shrugs. “It’s more about asking it the right questions.”

It doesn’t take long to understand Maher Inc. is a different business. It’s big business, done differently.

He has horses scattered right throughout Australia’s two biggest horse racing states, NSW and Victoria, maintaining his preference for a city, rural and beach base in each jurisdiction. “I can move horses to wherever, getting into the psyche of them,” he says.

As a result – because of the scale and precision of the operation – no trainer will have more winners in Australia this season.

He’s corporate too. If you don’t run into one of his horses on the track, you’ll run into his silhouette on a giant electronic billboard outside a major airport, part of a branding he’s never quite been comfortable with. Or you’ll see it at more obscure places such as the rolling screen at a petrol bowser. “A mate rang me from Gosford and he was at a fuel station. He said, ‘I’ve just seen your f—— hair at a gas station!’.”

He has an advisory board which he can seek guidance from. They’ve seen Maher win pretty much every big race Australia has to offer, from jumping marathons at his hometown Warrnambool, to stallion-making sprints and the Melbourne Cup, either training outright or in partnership with now Hong Kong conditioner David Eustace. The only one of the so-called modern day “big five” he’s yet to win is the Golden Slipper. On one day last year, his horses won more than A$14 million in a staggering burst, claiming The Everest (Bella Nipotina) and Caulfield Cup (Duke De Sessa) within minutes.

It’s fair to say Maher is redefining the limits of horse training, the mega stable in an era dominated by them in Australia.

So, how many horses does he actually train? Maher estimates he has about 390 in work now. It has been as high as 450. Staff? It’s about 200, although a minor restructure in recent months, which saw the exit of chief executive Ben Sellenger, has reduced the workforce by less than five per cent.

The relentless schedule means he often spends half the week in Victoria and half in NSW, where he now resides in Sydney. In this particular week, he spent two days in Melbourne, the next in regional Ballarat, flew to Sydney before driving to Bong Bong on the Thursday, Warwick Farm on Friday and jetting to Brisbane for the primary Saturday races.

“I’m a bit of a gypsy,” he says. “But as long as you’ve got the right staff, the right systems and the right culture at each, that’s the stuff I worry about. The culture is very important. You get one bad egg into a particular site, they can destroy the culture. It’s the most important influence on the staff, and that directly relates to a horse’s performance. If you’ve got that good atmosphere, you avoid that ‘it’s too cold, it’s too early (complaining)’. You don’t want that s— attitude.”

He then speaks about a group of university students who work at his Ballarat stable. They’ve become infatuated with the science of a racehorse, and have immersed themselves in Maher’s operation outside of their studies. He argues that he empowers his staff to use their own initiative because he can’t be in six places at once, but that doesn’t mean he’s not across what’s going on at each.

“I get people to use their initiative and their brain, and then I’ll get them to do it,” Maher says. “When you have a lot of staff, you get job satisfaction that way. You’re not telling them like a robot. You need them to think about what they’re doing and why. I think that’s pretty important.”

Maher’s “training tree” is evidence of that. While professional sporting coaches will often watch their assistants go on to further their careers in their own name, Maher is also shaping the next generation of Australian trainers. Eustace, Annabel Archibald and Jack Bruce are all successful having previously worked for Maher. He says it can be a disruption to his business, but a fact he takes pride in when they move on.

Unlike most of his peers, Ciaron Maher was never destined to be a horse trainer or a jockey because of his pedigree. While sons, daughters, nephews, nieces, grandchildren all seem to wander into horse racing because of a family influence, Maher had to find his own path.

His father John was a former rock band member and ran a dairy farm on the outskirts of Warrnambool, a coastal town in western Victoria. Maher’s main introduction to animals was through cows, but he also grew up around some horses, mostly chasing them on the dirt bikes he rode for fun. “I was a bit of an adrenaline junkie I suppose,” he says, pointing out one of his great passions in adult life is to ride motorbikes at Phillip Island, the host of Australia’s Moto GP, for leisure. He would be inspired by watching The Man From Snowy River, and try to emulate it in the paddocks of the family farm.

His interest in the thoroughbreds grew as a teenager in the racing-mad town of Warrnambool, which hosts an iconic three-day carnival each year, until he started competing as a jumps jockey. He was apprenticed to Colin Hayes and later represented Australia overseas, but by his early 20s, his height and weight were becoming an obstacle greater than any he had to clear on the track.

Maher then set out, like many ex-riders, to first learn off others, and then train. It included a stint with 12-time Melbourne Cup winner Bart Cummings, whose knack of preparing a horse for a target race was, and perhaps still is, unmatched. “There was no one better,” Maher says. “To go through a couple of springs with him was amazing.”

But he was ambitious and wanted to train himself.

Maher’s first Group 1 winner wasn’t just any milestone, it was in the Emirates Stakes during the 2007 Melbourne Cup carnival at Flemington with Tears I Cry, a 100-1 bolter. Naturally, owners flooded the young, mop-haired 26-year-old trainer with horses afterwards, hoping his sudden Midas touch would rub off on their own.

Unfortunately, most of those horses ranged in ability from middling to plodders that couldn’t-pick-their-feet-up. It almost broke Maher, often getting home from race meetings at 9pm and rising by 2am. But it also gave him an idea to go back to a similar cross which produced Tears I Cry, and the result was a longtime favourite in Akavoroun, which was plunged in betting before winning as a two-year-old on debut at the Warrnambool carnival.

“I said to the old man, ‘maybe Tears I Cry was a fluke, but maybe that mix works’,” Maher says. “Akavoroun was just a beast of a horse. That was pretty special. People have said to me, ‘when you breed one…’. I’m like, ‘yeah, whatever’. But it was pretty amazing.”

His success was steady. It would be seven years before he won a second G1 after Tears I Cry and he mainly made a name for himself with jumpers, then started shining with fillies. To get better, he had to grow. And that meant rolling with the big boys at Australia’s major yearling sales, including Magic Millions on the Gold Coast and Inglis’ Easter extravaganza in Sydney.

In recent years, Maher could sign for tens of millions of dollars of untried horses at any one sale and not many people would bat an eyelid. It’s easy when he has the backing of a lot of major Australian breeders and wealthy owners. But it wasn’t always the way.

Merchant Navy, the A$350,000 buy, helped change everything, and not just because he went on to be a dual Group 1 winner in both the northern and southern hemisphere, winning the Diamond Jubilee Stakes at Royal Ascot for Aidan O’Brien.

Asked how he felt putting everything on the line at those early sales, Maher says: “I used to (be nervous). I remember the first year I did it, I thought ‘f— this’. Australians like to pigeonhole you. When I first started training, it was like, ‘he trains jumpers’. Then you get an Oaks winner so it’s like, ‘oh, he can train fillies, but he’s never trained a colt’. I went to the sales and spent a couple of million and ended up with Merchant (Navy) and another horse called Reserve Street, who I had an opinion of.

“One of the first yearlings I bought was Another Wil’s mum and it cost $27,500 or $30,000 at Melbourne Premier and I was s——- myself. Then you’re buying stuff on spec for $600,000. That is risky. I understand it’s very risky. Everything is paid up for (now), a decent portion anyway. There will be one a year I go a bit rogue on still.”

Shortly before Merchant Navy won the G1 Coolmore Stud Stakes, Maher’s career was at the crossroads. He was suspended for six months and fined A$75,000 on stewards’ charges that conman Peter Foster was involved in the ownership of five horses he trained, including star mare Azkadellia.

Maher set out travelling the world during his short ban, learning from others, and then took on another daunting experience after his return on the day he assumed control of the main base of Australia’s other mega trainer, Darren Weir.

Maher had gradually doubled his business size with the acquisition of boxes tied to Rick Hore-Lacy and Peter Moody, but the day Weir was sensationally rubbed out in early 2019 for having possession of electronic devices, or “jiggers” on his Ballarat property, was when Maher started circling in another orbit (Weir has since faced criminal charges for using the devices on horses in the lead up to a Melbourne Cup carnival and wants to train again after serving his disqualification. He can reapply for a licence in 2026).

Maher was being lined up to head the nerve centre of the Weir dynasty at Ballarat, and the hundreds of horses and dozens of staff that came with it.

“My finance team told me, ‘this is suicide’,” Maher recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t care, we’re doing it anyway’. They said, ‘you’ll go bust’.

“I think the main thing was I was always prepared to risk it all … rather than not have a crack. I remember saying to the staff, ‘there are trucks lined up down the road waiting to pick up (Weir’s) horses. Get on the phones, I don’t care what you do, but as many horses as you keep will determine how many staff I keep’.”

They worked the phones all day to owners of Weir’s horses. Maher kept about 100.

It’s almost unthinkable to believe the Maher monolith can get bigger, especially when he’s now the father of an infant daughter, Eliza, but he stresses “we’re always geared up for growth”. Behind the fading locks, resembling nothing like his corporate logo these days, and country drawl is an intelligent and hungry mind now wanting to conquer international races, not just those in Australia.

Unashamedly, his focus is now on NSW as he tries to gain a greater stronghold in Sydney, a domain long dominated by Chris Waller, who is on the cusp of his 15th straight metropolitan training premiership.

“My goal is to get the best out of each individual horse, and if that costs me a bit of money, I don’t mind,” Maher says. “Consolidating is the main thing, and every year we’ve improved in NSW and we’ll look to take on …”

His voice trails off, almost too scared to say what no other trainer would even contemplate. Does he think he can take on Waller in Sydney?

“Yeah, I’m always up for a challenge,” Maher says. “There are similarities through the business and his business, but he’s been at it a few years longer than me. I can see how he keeps accumulating those horses.

“We’ll wear him down.”

And if one day he does, you can bet the boy from Warrnambool will still have the cluster of cows in the back paddock. He’ll probably get just as much pride out of them as anything else. ∎