Moments Of Truth: How Tetsushi Baba Found His Calling

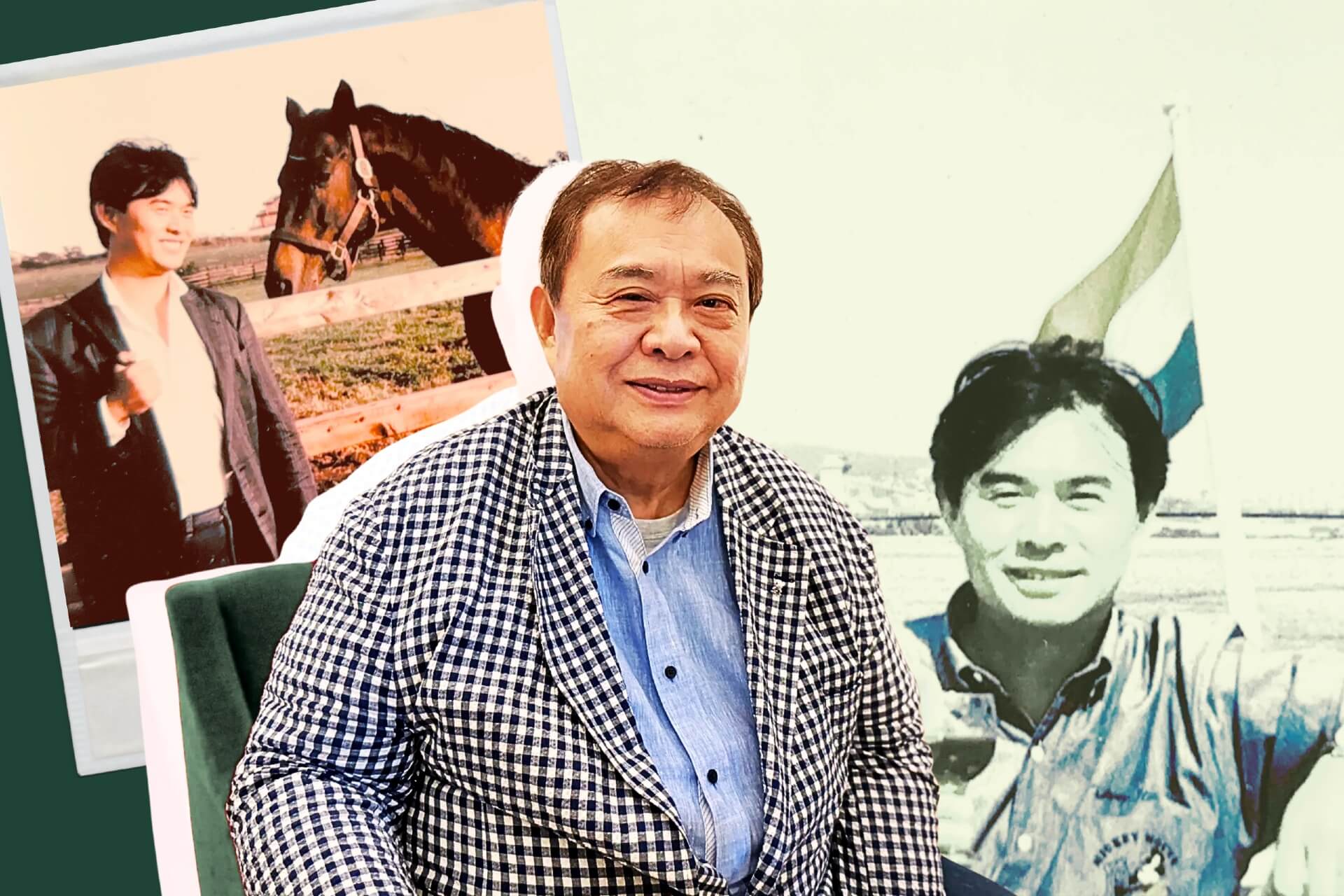

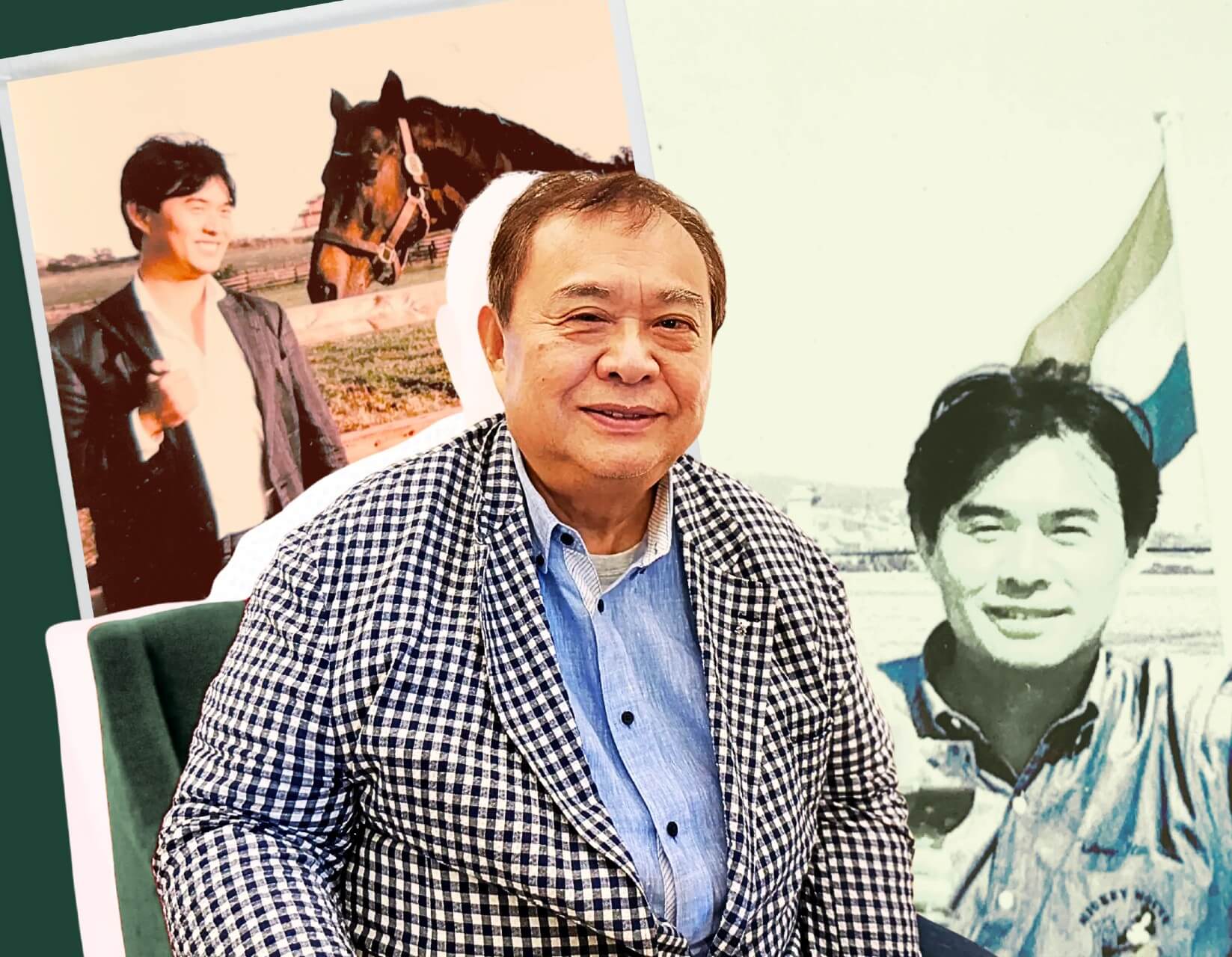

Retired racecaller Tetsushi Baba’s poetic commentary was a beloved part of the sport in Japan for more than 35 years, but he plotted an unconventional path to becoming an icon of sports broadcasting.

THE KYOTO CROWD cheered when the gates opened for the 2005 Kikuka Sho, but the noise was a brief, nervous release from the tension of expectation. Deep Impact was the 1.0 favourite to win the Kikuka Sho and with it Japan’s Triple Crown, and as the fans quietened and the 16 horses galloped on, race caller Tetsushi Baba knew what he said would be the soundtrack to history.

“Behold! Horsemen of the world, this is the masterpiece of modern Japanese racing!” he declared three minutes later as the brilliant colt strode to victory with the crowd in full voice.

Baba’s words carried the moment across the airways into households the length and breadth of Japan.

“I knew he was going to win,” Baba tells Idol Horse of his iconic line. “I had already prepared what I was going to say to look cool.”

Baba turns 75 this year. He recalls that autumn nearly two decades ago with crystal clear detail as he sits in a coffee shop in the lobby of the Swissotel in Osaka. The people milling around on this busy weekday afternoon, seeking shelter from the summer swelter outside, do not know the seated man by sight, but many would know the voice.

For 36 years, Baba covered racing and sports for Kansai Television, bringing a respect for the sport that was displayed in his meticulous research.

“I once asked the landscape department at Kyoto Racecourse how many swans were in the pond for a line like, ‘Even the swans in the pond are paying attention,'” he says. “They told me there were 163, so I used that line on another occasion.”

Not that Baba ever thought he was the star of the show.

“This applies to all sports, not just horse racing, but I don’t think sports commentary is good if you don’t respect the athletes. Therefore, the commentator should not stand out.”

Baba grew up with a fondness for sports broadcasting from a very young age and has covered numerous sports besides horse racing for Kansai TV, a subsidiary of Fuji TV.

“I’ve loved sports since I was a child. I was born in 1950, so when I was a kid, the only sports being broadcast were baseball, sumo, and pro wrestling.”

Through his childhood in the 1950s and 1960s, his heroes were Tochinishiki of sumo, Masaichi Kaneda, and Jun Hakoda of the Kokutetsu Swallows in baseball. When Baba’s sports-mad father returned from the war, he formed a baseball team with his seven sons.

“My dad was very good, and my eldest brother was even scouted by a professional baseball team. Although my dad was an amateur, there was no one who could beat him in the Tama area near Tokyo,” Baba said.

It wasn’t on the diamond that Baba believes the seeds were planted for his future vocation, though, but through his father’s unconventional lullabies.

“When I went to bed, my father would do a baseball commentary for me, saying things like, ‘Pitcher Otomo has thrown the ball!’ and I would supposedly fall asleep happily listening to it.”

The first time Baba encountered horse racing was in high school, when he was absorbed in soccer and even considered becoming a professional. However, he soon became engrossed in horse racing instead.

“I started watching horse racing on Fuji TV’s black-and-white broadcast in high school,” Baba recalls.

He was intrigued, but when he saw it first hand at the 1969 Arima Kinen in all of its explosive glory, he was transfixed.

“Speed Symboli won in a one-on-one duel with Akane Tenryu. I saw an amazing race right in front of me,” he says.

Now he was obsessed. The day after the 1970 Tokyo Yushun, he woke up at dawn and went alone to watch a thoroughbred auction in Chiba.

“Famous trainers like Tokichi Ogata were lined up, eating their gorgeous bento boxes, and I was eating a roll I bought in front of the station all by myself. There weren’t any other students like that. I just took pictures.”

During the first half of Baba’s university life, there were no lectures due to the lingering effects of the 1960s student protests, and he took on part-time work such as truck driving and delivering groceries at a U.S. military camp, where he also picked up English.

His first step into racing media came not through broadcasting but by producing pedigree catalogues with Toru Shirai, a senior from Waseda University who ran the Thoroughbred Pedigree Center in Shinjuku. Together, they launched the inaugural issue of Keiba Shikihou (Horse Racing Quarterly), and when Shirai discovered a chart Baba had created of sire results and prize money, it was developed into Shuboba-roku (Record of Sires), which later evolved into Keiba Nenkan (Horse Racing Almanac).

The horse Takeshiba O’s overseas start in the United States provided another turning point for Baba. Like many Japanese racing fans, he listened intently on a shortwave radio, and his racing obsession went to another level.

“I would even buy betting tickets at the Korakuen off-track betting facility, even though I wasn’t supposed to.”

He added, “At that time, there was an announcer named Iwao Kosaka from Radio Tanpa (now Radio NIKKEI) who said, ‘Good morning, everyone in Japan. This is Laurel Racecourse in the United States. The Japanese horse Takeshiba O is finally…’ It was so cool, I got shivers.”

Takeshiba O, a colt by China Rock, competed in the Washington D.C. International twice, in 1968 and 1969. Although he finished last both times, Kosaka’s commentary left a powerful impression on Baba.

“Listening to Kosaka’s call, I thought, ‘Horse racing calling is great,'” he says. “At the same time, when I watched Fuji TV, my senior Kiyoshi Sugimoto started calling in 1969. I would always record all of Sugimoto’s calls on a small open-reel tape recorder every week.”

Once he decided to become an announcer, Baba moved quickly. His first clue was in the phone book.

“I happened to find the name of a man named Hiromasa Kobayashi from Radio Tanpa in the phone book, so I called him.

“He invited me to his house, gave me papers with outlines of racing colors to fill in, and I would write them myself and go to the racecourse to practice calling from the front row of the second-floor seats.”

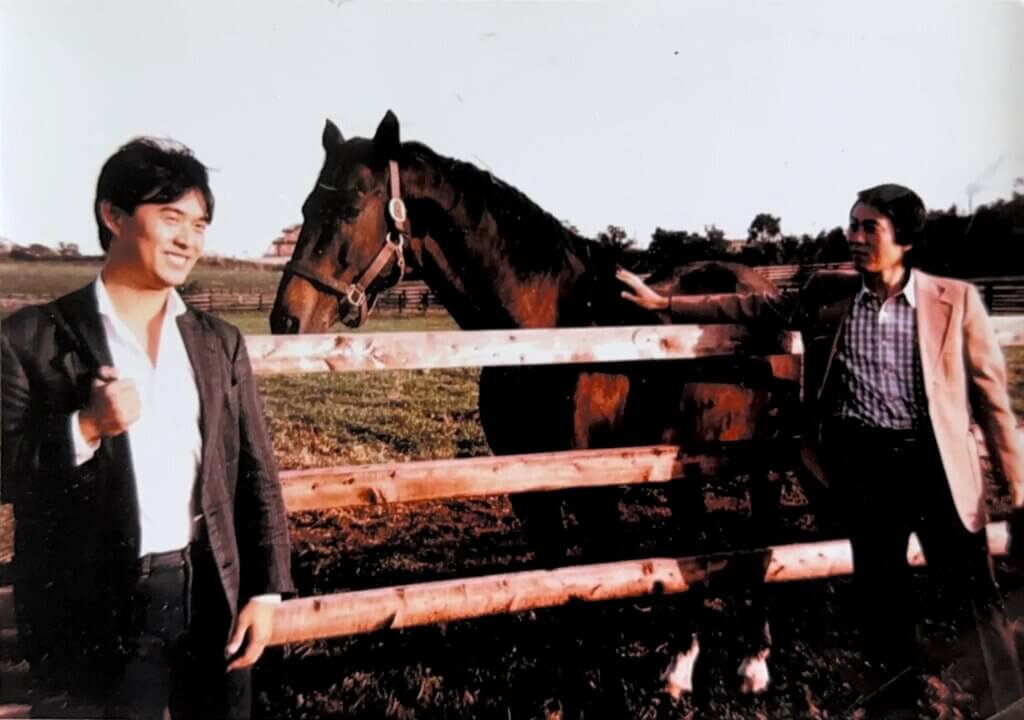

While in college, Baba spent two consecutive summers working at Shadai Farm in Hokkaido, gaining hands-on experience with horses through arduous 4 a.m. starts and even assisting veterinarians with pregnancy checks, a task that left future JRA officials surprised he had once performed.

It was here at the farm that Baba struck upon a realisation that would later change the fundamental way racing was described by commentators. As the “grandpas and grandmas” he worked with listened to Radio Tanpa while raising bedding, he noticed that not every horse in a race was mentioned.

“The workers would be cheering hard, saying things like, ‘So-and-so who was here before is running at the back today.’ Hearing that made me think, ‘I have to mention every single horse.'”

“I developed the belief that a commentator must call out every horse, even if they are at the very back or in last place. At that time, Fuji TV would only mention 5 or 6 horses. It was less about being a fan and more about the feelings of the breeders.”

In 1974, Baba joined Kansai TV as an announcer. However, he was not limited to horse racing as he had hoped and had to cover other sports as well. He recalls that the period when he was in charge of professional baseball—there were four teams in Kansai at the time—and F1 and Alpine skiing, which were broadcast live from overseas every year, was busy but a “valuable experience”.

“I’ve never been overseas for horse racing. But I had valuable experiences in places like Switzerland and Slovenia for F1 and skiing. However, when you’re in Kansai, Kyoto and Nara are cities of a thousand years.”

Baba’s signature style is to skillfully weave seasonal descriptions, haiku, tanka, and sometimes literary works like the poetry of William Wordsworth into his meticulous commentary. He says this comes from being close to ancient Japanese cities like Kyoto and Nara, as well as the influence of his senior, Kiyoshi Sugimoto.

“Sugimoto-san also has his own unique beat and rhythm.”

“He would speak in a low voice that felt like it was creeping along the ground. When the race starts, his tension goes through the roof, but then he inserts rather affected words. He called that ‘anko‘ (a filling).

“But he would tell me, ‘Baba, it’s not good to put in too much anko.’ I thought that was cool, but I couldn’t do it the same way.”

Baba, who became an announcer under Sugimoto’s tutelage, says he often imitated Sugimoto’s commentary at first. However, a director pointed this out, which became a turning point for him to establish his own unique commentary style.

“So, on top of the unique coolness of sports commentary, I added the four seasons,” he explains. “Since I was in Kyoto, and there were races like the Oka Sho and Kikuka Sho, I decided to study about cherry blossoms and chrysanthemums, flowers of the origin of the race names, and I started studying those things.”

“It’s so cool, I thought if I could incorporate even a little of something like Ki no Tsurayuki’s poem, ‘The winds that strew the cherry trees / a remnant of their passing / bring waves to a sky without water,’ into my call.”

What Baba emphasized was the importance of the seven-five rhythm, a metrical pattern unique to the Japanese language. He explained that this rhythm is not only used in haiku and tanka but is also found in popular songs.

Another one of Baba’s particularities was the precision of his expressions related to weather and atmospheric conditions. He said that during his active years, he would carry not only classical tanka poetry collections but also a dictionary of meteorological terms for reference.

“The study of weather is interesting. It also depends on the weather on the day of the race, of course.”

“For example, I would say things that might be a little affected, like, ‘The start is made through the steady spring rain,’ or ‘From a forget-me-not coloured sky.’“

The preparation of the words he wove into his commentary was not limited to classical literature and meteorological terms. Baba recalls that interaction with jockeys was also a crucial element.

Sometimes, he would ask jockeys such as Yutaka Take and Hirofumi Shiii about their impressions, sounds, and atmosphere during the race.

“I’d ask things like, ‘What does it feel like when you start?’. Then, Shii told me, ‘Baba san, sit on a chair, and I’ll pull it all of a sudden. That’s what the shock of the start feels like.’

Baba then said he had another memorable race and began to talk about the 1989 Mile Championship, where Katsumi Minai on Oguri Cap and Yutaka Take on Bamboo Memory fought a fierce battle.

“I asked Yutaka, ‘How do you feel about the next race?’ and he said, ‘Well, I have a tactic. ‘ He wouldn’t tell me what it was, so I went to Minai and said, ‘Hey, Yutaka said he has a tactic.’ And Minai said, ‘I don’t have any tactic. But I’m sure Yutaka’s thought of all sorts of things.”

On the fourth corner, Take’s secret tactic was revealed; Bamboo Memory suddenly made a big move on the outside, then Minai came up from the inside and stretched out again.

Baba said he can never forget the tears of Minai, who, after winning the historic fierce battle, said in an interview, “I felt like I lost again today.”

Regarding the skills and strategies of the legendary jockey Yutaka Take, who pushed Minai to a nose length, Baba recalled a comment made before the 2006 Kikuka Sho, where Meisho Samson was going for the Triple Crown.

“Yutaka also led that race with a horse named Admire Main. When I asked him before the race, ‘Can you tell me your tactic?’ he said, ‘Baba san, I’ll go the first 1,000 meters in 1:01, the 2,000 meters in 2:02, and the 3,000 meters in 3:03. If I can’t win with that, then so be it.'”

Admire Main maintained its lead, pulling away from the rest of the field until the fourth corner, but was passed by Song of Wind, who came up on the far outside, and finished third.

Baba spoke warmly about interactions with jockeys from the past, but described Take’s father, Kunihiko, as “still the person I like most in the world of horse racing,” and the 1977 Takarazuka Kinen, which was won by the “Heavenly Horse” Tosho Boy in a wire-to-wire victory as one of his most memorable races.

“I really liked Kuni-chan, he was so cool. He was tall, too. When Kuni-chan won the Takarazuka Kinen, he ran perfect laps of 12.5, 12.1, and 12.5 seconds, and just held on for the win. Both father and son have a beautiful pace.”

“So when Meisho Tabaru ran in the Takarazuka Kinen this year, I was hoping someone would mention it, but no one did; it was too old. The next day, I called Mamoru (Ishibashi) and said, ‘It reminded me of Tosho Boy.'”

When asked for his impression of recent horse racing, Baba’s lively tone when talking about the famous horses of yesteryear took on a slightly somber note.

“Stayers are completely ignored now. I liked horses like Indiana, Take Hope, Bell Wide, and the Mejiros. It’s a bit disappointing.”

“But I think thoroughbreds have reached their limit. They’re probably over-specced. So even horses like Kizuna have amazing acceleration, but those kinds of horses with a great burst of speed are scary.

“That acceleration can also become their fragility. It’s a double-edged sword, so I think that while the Japanese racecourses have certainly gotten better if they’re going to break 1:30 for a mile, I think it’s past the thoroughbred’s limit.”

Baba emphasized the importance of accuracy and speed in race commentary, using the 1999 Shuka Sho as an example.

“Accuracy. You must not make a mistake, no matter what.”

“Next, you have to call the horse’s and jockey’s movements as quickly as possible. Because if you look at the third corner, you can pretty much tell who’s going to win, so at the fourth corner, I mention all the names of the horses that look like they’re coming.

“So even if it’s Buzen Candle or Clockwork, I always keep them in my sight. I’m thinking in my head, ‘Clockwork is coming from the far outside.’ I need to be able to say the names even when 5 or 6 horses finish with a head-head or neck length.”

“I’m not bragging,” he added, “but in the 2002 Kikuka Sho, where No Reason fell, other networks were more than a second slower than me in calling out the horse’s name.“

“That’s the moment of truth for an announcer.” ∎