House Of Hayes: Legacy, Loss And The Rebirth Of A Racing Dynasty

David Hayes opens up to Idol Horse about the dynasty his father built, the brother he lost, Ka Ying Rising and a potential timeline on his latest Hong Kong stint.

WHEN THE LATE Queen Elizabeth made one of her many visits to Australia more than half a century ago, it’s fair to say the itinerary for a royal tour was a bit different to what it looks like now.

Just last year, her son King Charles made a lightning visit to Australia and the Pacific. Albeit jetlagged and still trying to prioritise his health after a cancer diagnosis, he was in Sydney on the day of the A$20 million The Everest, the highlight of a meeting which also featured a Group 1 race named after the monarch.

Organisers left no stone unturned to get him to Royal Randwick, however briefly, notwithstanding the monumental security operation which would follow.

King Charles didn’t appear.

It’s hard to imagine now, but in 1977 Queen Elizabeth and her husband, Prince Phillip, had an unusual destination during their trip: Lindsay Park.

The Queen had heard what had been built in the rolling hills outside Adelaide in the wine-rich Barossa Valley, and being a racing enthusiast herself, packed the binoculars and sought out a trainer by the name of CS Hayes to see what all the fuss was about.

Years earlier, Hayes was told he was mad for even considering it. Who would build a private training centre away from a city and its tracks, where all horses were typically trained in Australia, and take on the financial burden as well?

But inspired by a visit to the United Kingdom, CS Hayes risked it all. He said there was a better way to prepare horses, far away from the big buildings and tight turns of city courses, among nature and the birds, with elevated gallops and sprawling yards. His vision, he reasoned, would change the face of Australian racing. By 1965, it was a reality.

Not everyone agreed, least of all some of his owners who yanked horses from the stable and demanded they stay closer to home. Punters were bemused. Rival trainers sniggered.

But Queen Elizabeth was intrigued, so too Australian Prime Ministers Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke, who also made official visits to the Angaston property in South Australia, at a time when horse racing was far more accepted within the corridors of power that house the country’s decision makers.

All these years later, CS Hayes’ son, David, is perched up on the second level of the Sha Tin training tower. It’s a perfect Hong Kong morning, sun glistening, peeping above the mountainous backdrop, which disguises mainland China. Who would have thought a typhoon had swept through the day before? As horses’ hooves gently kiss the dirt surface metres from the outside running rail, David Hayes’ eye wanders across the track.

“I’m an early riser,” Hayes says. “I just enjoy the vibe of it all, watching trackwork here. The thing I look at on slow mornings like this, is that they’re relaxed, and if they’re not relaxed, you’re trying to work out ways to make them relax. If they’re not going around correctly, you’re always fidgeting.”

There’s no need to fidget. Hayes’ brigade shimmy around the track like they’ve been living the relaxed life in the scenic Adelaide hills, the starting point for an Australian training dynasty closing in on 80 years, with all four of David’s children now working under the Lindsay Park banner.

On Saturday, Hayes will perhaps have his biggest ever moment on a racetrack when Hong Kong superstar Ka Ying Rising starts favourite in The Everest. Hayes will wear an ageing suit, a mix between beige and off white, daring not to change out of it after wearing it at the start of Ka Ying Rising’s winning streak, and promising to keep wearing it on raceday until they were beaten. Ka Ying Rising is gunning for win No.14 in a row.

Is he the best David Hayes has ever trained?

“Not even a question,” Hayes fires back to Idol Horse. “I think if he does it for another year, there’ll be some good seasoned race people say he’s the best they’ve ever seen, too.

“You can’t compare him to Black Caviar until he’s done it for three seasons. What he’s doing is like Black Caviar. I wouldn’t say better, but the same. And if he keeps going, maybe he could be compared to her or Winx.

“He’s just totally dominant.”

How Hayes and the Lindsay Park empire came to conquer Australian and Hong Kong racing – winning hundreds of Group 1 races around the world, including the Japan Cup – is a testament to one man’s vision, a tale of triumph and the tragedy of a plane crash, of family, failures and sheer willpower to succeed.

“The future belongs to those who plan for it.” – Colin Hayes.

It’s a well worn expression these days, but in an era not long removed from World War II and The Great Depression when most people lived day to day, Colin Hayes was already questioning how he could make things better for the future.

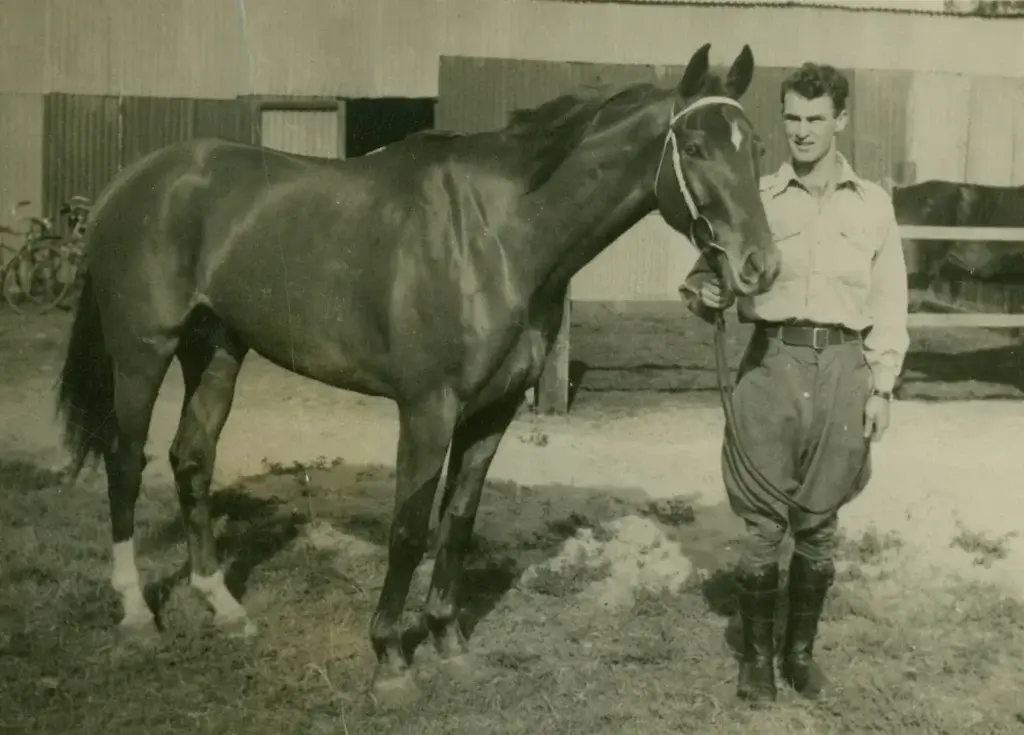

His own career is traced to the nine pounds he paid for a steeplechaser called Surefoot. By 1948, Hayes was not only training the horse, but also riding him as an amateur, and in the Great Eastern Steeplechase the pair managed to finish third.

If you wanted to know how much Surefoot meant to Hayes and his early days in horse racing, it was there for all to see on the door of his new stables in the Adelaide suburbs.

Surefoot Lodge.

Having slowly and steadily built his team of horses, Colin Hayes won his first training premiership in Adelaide by 1956. But he wanted more, and in a time when overseas travel was far more inconvenient than it is now, he headed to the United Kingdom to see how it was done in the northern hemisphere.

When he returned, the seed had been planted for the purchase of the Angaston property, an 800-hectare beauty outside the Adelaide basin to be his new home from 1965. The Lindsay Park dynasty was spawned.

Colin Hayes didn’t just want to train racehorses, he wanted to breed from Lindsay Park too. He stood stallions and found wealthy overseas owners, including British businessman Robert Sangster and Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the former deputy ruler of Dubai. He teamed up with Sangster to break new ground in Australia: shuttling stallions from the northern hemisphere to the southern hemisphere depending on the season.

“It was the Hunter Valley of Australia at that time,” longtime Lindsay Park lieutenant Tony McEvoy says.

As Colin Hayes’ horses criss-crossed the border winning races in either Adelaide or Melbourne, the second half of 20th century racing in Australia was defined by three men: Bart Cummings, TJ Smith and Hayes.

Cummings finished his career as arguably Australia’s most recognisable horseman, a winner of 12 Melbourne Cups and owner of so many witty one-liners. When a health inspector once visited his stables and told him there were too many flies, without hesitation, he said: “How many am I allowed to have?”

While Cummings’ horses were mostly ridden conservatively in races, saved for a withering finish or a big target race at the end of a preparation, Smith’s horses (and those later of his daughter, Gai Waterhouse) often raced on the speed and with verve. Smith won an astounding 33 straight training premierships in Sydney, a master of massaging owners and the media with his high-pitched voice and eccentric personality.

Between them, they were the holy trinity of Australian horse racing for decades.

“In the old days, you were either a Hayes man, a Cummings man or a TJ man,” David Hayes says. “Dad used to clash a bit with Bart. They were both from Adelaide, two big boys in the small pond.

“And TJ was a friend of dad’s. He would stay with dad if he was in Adelaide. But he was very competitive.”

Says Hall of Fame trainer John Hawkes: “Those three trainers – Bart Cummings, Tommy Smith and Colin Hayes – we will never see their like again. They were all ahead of their time and were real champion trainers in their own right.”

There are sliding doors moments in everyone’s life, and David Hayes’ came on a cold and wet Saturday afternoon in the middle of the Adelaide Oval, the city’s main sporting field which hosts Aussie Rules and international cricket matches.

David was a strapping key forward playing in the second-tier competition against Port Adelaide. For a reason he can only put down to the races being called off, David said Colin came to watch him this miserable day. With designs of progressing his career to the Australian Football League (his son Will would later reach AFL level, playing 13 games across the Western Bulldogs and Carlton), which was bordering on professional at the time, a 20-year-old Hayes watched as his side were blown off the park. He barely got a kick.

On the way home, Colin turned to David.

“What do you tell the owners if they’ve got a Melbourne class horse?”

“Oh, really good. Keep going, it might win a Group race.”

“What do you tell them if they’re Adelaide class?”

“Well, it’s winning in Adelaide and hopefully it can progress to Melbourne.”

“What do you tell them if you’ve got a country horse?”

“Well, it’s probably not good enough, and you should get rid of it.”

“Do you think you should retire?”

Hayes was stunned.

“I had a bad day,” he says. “He retired me at 20, so I was playing very young in a men’s comp.

“But I would have loved to have played on a few more years, but he was unwell. And Peter and dad had personality clashes. He chose me to be the next trainer of Lindsay Park at a very young age.”

Colin’s other son, Peter, was a very talented horseman. But he saw the world in a different way to his obsessive father, who thought horses came first, second and third. Peter wanted more from his life, and so decided to go out training on his own, free from his father’s shackles.

By 1990, Colin Hayes’ health was deteriorating and he retired from training. At the age of 28, David Hayes was in charge of the famed Lindsay Park – and he couldn’t have asked for a better start.

His first full year of training was like a dream.

A tiny gelding his father took over from Cummings, Better Loosen Up, cut a swathe through Australia’s weight-for-age ranks, winning the Cox Plate from an impossible position and going on to win the Japan Cup, still the only horse from Australian shores to do so. Every week Better Loosen Up wasn’t running, it seemed like Zabeel was winning.

On Derby Day at Flemington, arguably Australia’s best day of racing, Hayes won a staggering six races. You couldn’t have wiped the smile off his face with a sledgehammer.

“That was a dream for a young trainer,” David Hayes says. “You couldn’t have scripted a better start.”

It was only a few years later David Hayes won the race every trainer in Australia grows up coveting: the Melbourne Cup. Jeune’s success in 1994 for Sheikh Hamdan also opened his eyes to the world. He flew to Hong for a visit and was hooked.

“I was the youngest ever (trainer) employed here,” David Hayes says. “It did surprise a few people because I just won the Melbourne Cup and was the leading trainer in Australia when I left.

“But I just came here for the international races and thought, ‘gee, this is a little bit different than what we do at home’. And the hardest thing to get here was to convince dad and get his blessing to go. And I had to get Peter to come back and train.

“Once I got dad on board and Peter back on the job, Peter retired from his own training and went to train for Lindsay Park. It was smooth sailing.”

Like many fathers and sons, Colin and Peter Hayes loved each other. But working alongside each other, it was an oil and water mix.

Most people thought David would one day eventually assume control of Lindsay Park from Peter, not the other way around, as David scrambled to set up a succession plan having had his head turned by Hong Kong.

Instead, Peter returned to the family’s business fold as Colin slipped into the twilight of his life. He died in 1999 at the age of 75.

Colin took his final breath at Angaston, the property he had the vision to build more than 30 years earlier, with Peter at the helm. He would go on to win three of the next five training premierships in both Melbourne and Adelaide.

“Peter arranged himself a work-life balance, and that was frowned upon in those days,” McEvoy says.

“You were either all in or you weren’t. CS was all in, David was all in and Pete, he was a great trainer, but he had the structure organised to do other things. That was frowned upon. It didn’t make him less of a person or trainer.

“It just made him different.”

One of Peter’s hobbies was flying planes.

On a March day in 2001, he boarded a light plane as a passenger bound for Victoria. He was interested in buying the aircraft and sat alongside the pilot on the test flight.

They never made their destination. Both the 67-year-old pilot and Peter Hayes, 52, died in the crash.

“I was waiting for him at the stables and we were going to trot the horses up at 3 o’clock … and he didn’t turn up,” McEvoy says. “It was very unlike him. Then I rang and he didn’t answer.

“It was an incredibly sad day.”

David Hayes was on a golf course in Macau when his phone rang. Two years after he lost his dad, he was told the shattering news Peter had died in a plane crash. He immediately chartered a helicopter back to Hong Kong, then flew straight to Australia as Peter’s death made worldwide news.

“And I can remember arriving at the airport and it was a media scrum,” David Hayes says. “I was quite taken back. It was a horrible time and it was terrible for Peter’s family and everyone involved.

“Peter’s attitude was, ‘there’s more to life than training’. And dad’s attitude was, ‘training is life’. And I’m more dad’s way. But Peter had outside hobbies he wanted to pursue. One of them killed him.”

McEvoy stepped up to take the reins.

As a young apprentice jockey, he joined Lindsay Park in 1976 when Colin Hayes rang the chief racing writer at the local newspaper and asked if he knew of any promising young riders in the state. McEvoy was the recommendation, but Colin Hayes said he would only take him if he came from a good family. He fitted the bill.

“It was his way or the highway,” McEvoy says. “He had his systems in place and he was the best.

“Everyone that worked for him had respect for him, and we all couldn’t believe our luck we were working in such a high quality place. CS was a very good boss. As long as you worked hard, you were fine.”

Shortly after, David Hayes finished his 10th year training in Hong Kong. He had won two premierships and had raised a family – children Ben, Sophie and twins Will and JD – in the city. He and wife Prue had four children under five at one stage, and with the kids approaching high school age, he decided to return to Australia, becoming the youngest ever to retire from the Hong Kong training roster at 40.

Jockey Club chief executive Winfried Engelbrecht-Bresges shook his hand and left with a parting word.

“Once the kids are grown up, we’d love to have you back.”

One of the Hayes family’s last business moves before Peter’s death was to purchase a property at Euroa in regional Victoria in 1999. It was on the road between Melbourne and Sydney, and as Adelaide’s racing scene started to struggle, David Hayes thought Lindsay Park’s migration should be from the rolling hills of the Barossa to the serene countryside of Euroa. They had originally used the facility as a pre-training centre, but David thought it could be so much more.

He made it his mission upon his return to Australia to shift the entire operation, mirroring the vision his father had almost 50 years earlier. It came with enormous heartache, both emotionally and financially. He poured A$21 million into the new facility, taking out a bridging loan while selling the old Angaston property off in parts.

McEvoy planned to move there, but his teenage daughter said she wouldn’t go. It was a fight he knew he wouldn’t win. It was also the first step to him eventually leaving Lindsay Park and going out to become a Group 1-winning trainer on his own, and now with son Calvin.

By the time Euroa was fully operational, Lindsay Park had cut their horses to 100. Winners were almost impossible to come by as horses and humans grappled with the new system.

“David loves success,” McEvoy says. “No one loves it more than David. When he couldn’t train a winner, it was horrible. But they stayed on task and, as you do, they got through it.”

Says David Hayes: “It was a horrible time because people were saying, ‘why on earth would you sell Lindsay Park? And set up on your own doesn’t work’.

“But they were making judgments and comments, they just didn’t know the process and how things happen. And it did take a bit of time, but when it came good, it came good in a big way.

“I really believed in the property and kept pouring money into it. And I think history says it’s been a great move for the boys because it’s the biggest private training centre in Australia smack in the middle of where you want between Victoria and New South Wales.”

Hayes’ second coming in Australia was dotted with success, but with an eye to what was ahead.

The future belongs to those who plan for it.

First, it was David’s nephew Tom Dabernig who joined him in a training partnership, followed by his eldest son Ben. But with little notice and his kids all adults, Hayes answered a call from Engelbrecht-Bresges he thought might never come again. The Jockey Club wanted him back in Hong Kong.

After the blood, sweat and tears of taking Lindsay Park back near the top, why return to Hong Kong for the 2020-21 season?

“I got offered an opportunity of a job where thousands of people apply for it,” David Hayes shrugs. “So, I just thought, ‘I loved it. I left it on a high and I loved the two days racing a week’. I love the professionalism of the Jockey Club, how everything’s taken care of.

“And I thought it would be just a nice way to finish my career up here and give the boys some space. Ben trained with me and we had 17 Group 1 winners together and when he won with (Mr) Brightside, they said it was his first. And I said, ‘no, it’s not. It’s his 18th’.

“But when they win them now, they get the credit for it. There’s no David Hayes, no Colin Hayes. It was like after dad retired there couldn’t be whispers, ‘of course, it’s Colin’. That’s a bit the same with the boys.”

All three of Hayes’ sons – Ben, Will and JD – are now part of the official Lindsay Park training partnership. Sophie’s role at Lindsay Park is as the business manager, with oversight from Prue in Hong Kong.

David Hayes keeps his distance, and joked the only time he’s called is to mediate any dispute between the boys about a programming decision or gear change they can’t all agree on. “I’m a bit like Judge Judy,” he laughs.

But the court of public opinion suggests the boys can train and will carry the Lindsay Park legacy for another generation.

Before Ka Ying Rising was sold to Hong Kong, the sprinter went through the Lindsay Park machine in Australia. He trialled at Flemington and the nondescript Moe. Blake Shinn rode another horse against Ka Ying Rising and immediately called David Hayes in Hong Kong.

“What was that horse you had? Can you help me get on him with the boys?”

Hayes had to break the news to him he was on the way to Hong Kong, where he’s morphed into the top-rated horse in the world. He’s not only emerged as a national hero, he’s also helped save David Hayes from a difficult return to the city where he was secretly on the brink of quitting.

“In the middle of COVID, I didn’t think I’d last too long,” he says. “I wasn’t enjoying it.

“The Jockey Cub did an incredible job to keep racing going, but we were under incredible restrictions. We were getting tested every day up the nose and we weren’t allowed to do anything except for the races at work.

“And I didn’t get to know my owners because there were no owners. I was losing a lot of horses because they didn’t know me. I had three of the biggest owners in Hong Kong leave the stable and I wasn’t enjoying it.

“I said to Prue, ‘if things don’t change this year, I am going to hand my resignation in’. But we really put our heads down, the city opened up, COVID ended, I got my relationships back with owners and started training a lot of winners.”

No one can understand the pressure of training a horse which, minutes before he ambles onto the track at Sha Tin, has a price on the mega tote boards reading $1.00 in the punting mad haven. When Ka Ying Rising wins, the Jockey Club hasto pump money into the pool just so punters can get a tiny dividend.

Hayes says he rarely gets nervous before Ka Ying Rising runs. At Royal Randwick for the world’s richest turf race, he has to beat Australia’s best in their own backyard.

Ka Ying Rising can finally right his Everest wrong.

“He’s got nothing to prove,” David Hayes says. “But to travel away, it’ll be a massive tick and it would probably convince a lot of people that he is as good as people are saying. There are some doubters there because he hasn’t done it away from Hong Kong or Sha Tin. Probably a legitimate concern, but I don’t need to worry.”

A lot of people would have forgotten, but Hayes trained the very first favourite for The Everest in Vega Magic back in 2017. The horse rushed home after a horribly wide run. He finished second. Hayes, through gritted teeth, describes it as “not one of (jockey) Craig Williams’ best”.

Win or lose, David Hayes will be back on the plane to Hong Kong straight after the race, plotting the next chapter of a remarkable family dynasty and the Lindsay Park legacy.

He wants a Hong Kong training premiership as part of his second coming, and it will have to come soon with Australia calling. The kids and grandkids can’t wait much longer.

“I don’t want to train until I’m 70,” he says. “I want to actually get home, probably be the chairman of Lindsay Park, not the trainer, and then enjoy my grandchildren and my children. I’ve probably got another three to four years here.”

It’s spoken like a typical Hayes, always with an eye to what’s next, what’s hiding over the horizon. Somewhere up there, CS would be up there, nodding his approval.

The future belongs to those who plan for it. ∎