Rachel King The New Queen Of Japanese Racing

Rachel King’s journey from point-to-points as a teenager to the top tier of racing has been remarkable. Adam Pengilly sits down with the British-born jockey to talk horses and her celebrity status in Japan.

IN THE CORNER of a little restaurant in Hokkaido is a shrine to a jockey, the likes of which Japan has never seen before. Rachel King hadn’t visited previously, but her pictures adorned the walls. Photos of her being interviewed, holding up mobile phone footage of herself, waiting to be legged aboard a horse.

Then, King walked into the restaurant to have a meal.

“They just looked, and it was a proper double take,” King laughs. “They lost it, absolutely lost it. People like that are part of an unbelievable culture which loves their racing.

“The number of restaurants I’ve been to, walking down the street, train stations … I haven’t been recognised in one restaurant or walking down the street in my life in Sydney or the United Kingdom. I go to Japan and to a café, they just go insane. I feel like a footy player would here (in Australia).”

It’s strange for an athlete to be adored and adulated so much in a part of the world which is not their regular home, but ask King what it’s like to walk down the street on the north-western fringe of Sydney and there will barely be a second glance. In a sports mad culture such as Australia, that is reserved for the likes of footy players in the National Rugby League or Australian Football League, as well as top cricketers. Jockeys? Not so much.

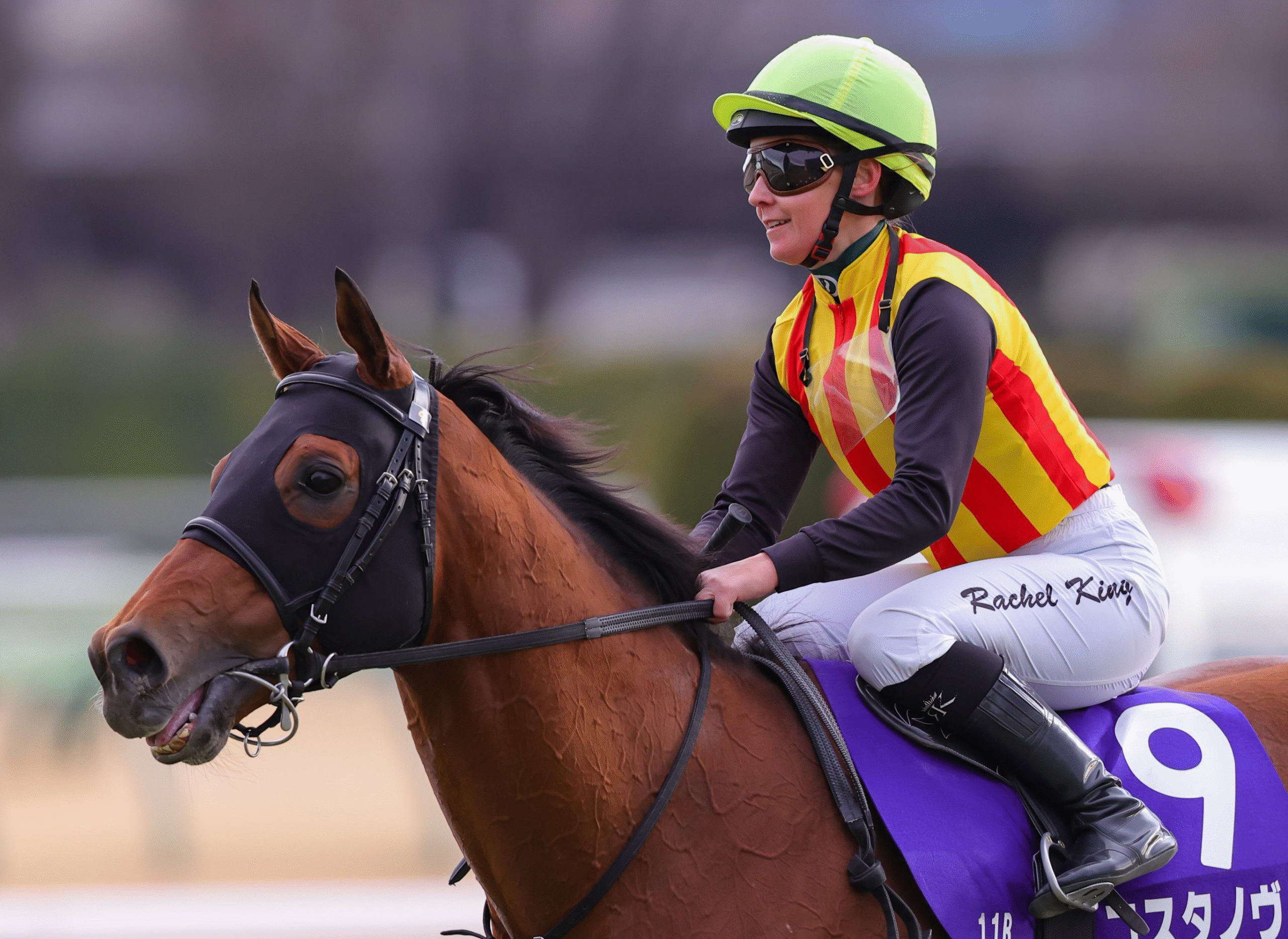

In Japan, it’s a different story. She might be King by name, but she’s fast ascending to queen by nature in the Asian country, which went mad over her becoming the first female jockey to win a G1 flat race in Japan, saluting aboard Costa Nova in the February Stakes earlier this year. The news created just a ripple back home in Australia, even if it was a seismic achievement for the Japan Racing Association.

“I’ve probably never been so confident riding in a Group 1,” King says. “My results in Japan had been good, but on the dirt … there were probably some question marks if I had adapted, to be honest.

“I’m very proud to be the first female (to win a G1 flat race), but I also love nothing more than being treated as just a jockey. I’m proud of it, happy about it, but I also like to be just an international jockey. That’s how I looked at it, rather than the female aspect.”

For years, King has tussled with some of the biggest names in world racing in the ruthless Sydney jockeys’ room: James McDonald, Hugh Bowman, Kerrin McEvoy, Tommy Berry, Jason Collett, Nash Rawiller, beaten them all at various times. Never has she considered herself a female taking on the boys, just another jockey.

To understand what makes Rachel King, a trailblazer in so many ways, tick is to know there’s only ever one reason why she does what she does: the horse.

It’s a sleepy mid-winter meeting at Warwick Farm in Sydney and King is sitting on an old bench out the front of the jockeys’ room speaking to Idol Horse, as scores of trainers, fellow jockeys, owners and stewards breeze past near the mounting yard. She has a brief break between races.

Her smile widens not when she’s talking about the horses she’s riding later that afternoon, or some of her best G1 winners, but when she’s regaling a tale of a local showjumping competition.

King has two off-the-track horses she looks after in their retirement: Military Mission, a multiple G2 winner in Australia who was 10th in a Melbourne Cup; and Paths Of Glory, another dual stakes winner who retired with A$500,000 in prize money. Their resemblance is uncanny, both are greys, both came to Australia from UK trainer Hugo Palmer, and King won on both during their racing careers.

Before each had run their last race, King had already lobbied connections to look after them in retirement. They agreed. It didn’t cost her a cent, and the satisfaction she’s getting out of it trumps any money she earned riding them in races.

Paths Of Glory has been a showjumping project for King, who gently has moulded him into a horse capable of competing in a second life away from the racetrack. One of his new sparring partners is Nature Strip, Australia’s former champion sprinter who won The Everest and at Royal Ascot before exploring his own equestrian pursuits.

“My horse actually won (a local show) and Nature Strip was third in the class,” King says.

The prize?

“I won like $100 or something,” she laughs. “I showed (husband) Luke (Hilton) and I was screaming, ‘I won some prize money’. He was like, ‘how much?’ I was happier (with that) than any winner. I don’t care if I don’t win any prize money at all. I’ll be happy to get a ribbon. I’m just passionate about the horse. Even all the other jockeys say I’m that pony mad little girl. That’s just me. I want to take every horse home and I’m fanatical about the animal.”

Killultagh Thunder is one animal King will never forget, the 10-year-old jumper she rode at her first race ride in County Cork. King was just 16. The horse’s trainer, Adrian Maguire, had to borrow a saddle and when he handed it to the tiny rider, she almost dropped it. King estimated it was so heavy she might have been lugging five to six stone carrying it around. By the time horse and rider made it to the second last fence in an Irish race, both were weak. King was unseated and her first experience as a race jockey has forever been burned in the memory since.

After that, her career was a series of false hope and false starts. From National Hunt racing, point-to-points, even clerical work mixed with morning gallops to stay involved, no one could have envisaged a girl from a tiny Oxfordshire village who was struggling to ride a winner in the first six months of her apprenticeship in the UK would ever make it as a professional jockey.

It all changed when she took a leap of faith to move to Australia, first joining as a track rider for the Bart and James Cummings stable. King never got to know the real Bart Cummings. His health was ailing after she arrived, and, by her own admission, at first she didn’t understand his legendary standing in Australian racing as a 12-time Melbourne Cup winner.

“I had no idea who I was going to work for,” she says. “I was completely ignorant about knowing anything about Bart before I came. I just said, ‘I’ve got a job through a friend’. Once I was there, I was in awe. I started realising what he had done and what kind of person he was, but I never got to really actually experience him.”

Cummings was a man of few words and witty one-liners. A health inspector visited his stable one day and told him there were too many flies. Without missing a beat, Cummings replied: “How many am I allowed to have then?” He preached patience with his horses, preferred them to be ridden quietly, and always prioritised their biggest race of the campaign.

King’s next employer was similarly a revered figure in the sport, but polar opposite. It’s impossible to talk about the Rachel King story without talking about Gai Waterhouse, a Hall of Famer who smashed every glass ceiling there is in Australian horse racing. She’s colourful, vibrant, opinionated, demands her horses be ridden to lead or on the speed. Basically, everything Cummings wasn’t.

“I think of her as my mum in Australia,” King says. “As much as we’re close in a professional relationship, we’re close outside of it as well. I know if I ever need anything, need to get in touch with anyone, she’s the first person I call, no matter what.”

King came to work for Waterhouse with no apprentice licence, or even a promise she would start one. In fact, Waterhouse knew she had an administrative background and wanted King to fill a vacancy in the stable’s office in between riding trackwork. It was only weeks after King started at Tulloch Lodge, Waterhouse entrusted her to travel with a horse to Brisbane for the Queensland winter carnival.

“I remember getting in the truck and saying, ‘where’s Brisbane?’ They’re like, ‘it’s going to take two days to get there’. I didn’t have a clue. No idea. She told me I was going for two weeks with one horse. I stayed for three months and I had eight horses.”

The stable won a stack of races, and Waterhouse knew she had someone she could trust in King. It was only shortly after King returned to Sydney when she received a phone call from Waterhouse one night. It was 9pm, unusual for Waterhouse to be ringing so late, and even more unusual was that King was awake to receive the call.

“She said, ‘I need you to fly to France tomorrow and pick up this horse and take it to America’,” King recalls. “I was like, ‘what are you talking about?’ She said, ‘don’t come to work tomorrow morning, you’re on a flight tomorrow afternoon’. Pick up this horse (Pornichet) from Chantilly, he’s got an entry in the Belmont Derby and then you’ve got to go back to England so you can do his quarantine. I literally got on a plane with the horse in a cargo (hold) and I’d never done any of this before … and I don’t speak any French.”

For the next 12 months, King was persistent with Waterhouse about one thing: she wanted to become a professional jockey in Australia. She’d earnt her trust, now she wanted her backing to start a career. It was only when Hong Kong trainer Mark Newnham, at the time Waterhouse’s assistant, took King to the offices of Racing NSW to sign her apprentice papers did Waterhouse realise how serious she was.

King started small, riding winners in far flung places in regional New South Wales, then progressed to provincial areas before making her mark in the city. If ever there was a sign of the respect Waterhouse had for her apprentice, it was a Warwick Farm meeting in 2017. King was riding a moderate horse called Puppet Master, trained by Gary Portelli. As the horse strained in the finish, he was squeezed inside and out, forcing King to lose balance and crash to the turf after the winning post.

“She came over to that gate and got me,” King says, pointing across the paddock. “She was walking me across the enclosure. I’m fine, but she’s going to me, ‘I know you’re OK, but you’re going home’. I said, ‘Gai, I’m fine’. She says, ‘you’re going home’. She gave me the biggest talking to. I looked like that little kid being told off.

“As hard as she was, she was amazing. She’s taught me if you don’t put in, you won’t get anything out of it. You’ve got to work hard for it. I worked there for a number of years and was apprenticed to her, but I still never miss working there each week.”

Says Waterhouse: “If I like people, that’s half the battle. I just had a feeling with her she could do the job. She’s never let me down.

“She’s beautifully balanced on a horse and she wants to succeed. The biggest thing is wanting to succeed. And she’s stuck at it over a good period of time. A lot of girls don’t. They just can’t do it. They think they can, but they can’t. The biggest thing for Rachel is she doesn’t have to waste.”

Sticking at it has led King to the other side of the world as she embarks on another short-term JRA riding contract. She says she’s used to the jockey lockdowns and occupying herself with Netflix on supplied iPads (Ryan Moore’s favourite is listening to talkSPORT) and finding her name in Japanese in formguides. In Japan, King feels it’s a “mix of her two homes in Australia and the UK”.

And what she likes more than anything is jumping on horses other jockeys can’t seem to work out.

“I love the challenge,” she says. “If you can turn a horse around or find something that clicks for them and get that extra little bit out of them (that’s satisfying). I never want to be at the stage where I go, ‘I’m comfortable where I am’. I just want to be better. Whether I go to Hong Kong or Japan, I want to be better.”

And if she is, there might be more than one restaurant in Hokkaido with a shrine to King, a new queen in Japanese racing. ∎