When Racing NSW drew up a list of potential investors for The Everest, the world’s richest horse race on turf, a billionaire cricket fanatic who has dabbled in everything from tech to private equity and even dog food wouldn’t seem likely.

But last month, a rare opportunity to become involved in the Australian racing phenomenon was allocated – and it went to businessman Michael Gregg.

To say a few eyebrows were raised would be an understatement.

Gregg’s Mulberry Racing business, in which his jockeys carry the bumblebee colours of his beloved University of NSW Cricket Club in Sydney, the home of Australian greats such as Geoff Lawson and Michael Slater, is only in its formative years.

The best anyone can ascertain about Michael Gregg’s initial interest in horse racing was when, out of the blue, respected horse trainer Brad Widdup picked up a phone call from an unknown number in 2019. On the other end of the line was Gregg, who told him he was interested in becoming an owner in Australian horse racing.

At the time, Widdup was at the crossroads of his own training business. He had only just lost his major owner, Damion Flower, who was arrested as part of a major police sting on the importation of cocaine from South Africa on commercial flights (there is no suggestion Widdup was aware of Flower’s activities). Flower would later be sentenced to 28 years in prison.

Widdup’s small team at Hawkesbury on the north-west fringe of Sydney had always punched above its weight, and Gregg had a friend who would compile ratings on various races throughout the state. Widdup always featured highly.

After the initial conversation, Gregg chose Widdup to be his trainer, and they started with just one horse the next year, The Grundler. His racetrack performances were modest: he broke his maiden and his biggest success was his second and last win, a Class 1 at Goulburn.

By 2021, Gregg bought for Widdup again, this time a Savabeel sprinter later named Jedibeel, who won the G2 Challenge Stakes earlier this year and has competed at Group 1 level. Their partnership has continued to grow to the point where Gregg has now sent Widdup to the United States to purchase bloodstock, and they paid A$700,000 for a Home Affairs filly at Gold Coast’s Magic Millions sale earlier this year.

So, how has Gregg made his fortune?

Much like his embryonic horse racing business, Gregg also spied an opportunity to invest in a company in its early stages, and it has netted him a fortune (The Australian Financial Review estimated his worth to be A$1.1 billion last year).

His biggest gamble was being one of the first investors in WiseTech Global, an ASX-listed software giant which has netted big returns for its early supporters. Gregg has also been heavily tied up in private equity as one of the founders of Shearwater Capital, and has been a major investor in biotech business GPN Vaccines.

When his application to take over The Everest slot vacated by beleaguered gambling giant The Star lobbed on the desk of Racing NSW, it aligned with the outside-the-box thinking the race covets.

The Everest already had gambling behemoth Tabcorp, breeders Coolmore, Yulong and Godolphin and auction house Inglis among its slotholders, industry giants known across the world. Why not add a billionaire tech specialist for something different?

So, what is Mulberry Racing actually about? And what are they doing paying an undisclosed sum to be a slotholder in The Everest for the next three years and promising to promote the race in a different way?

Mulberry Racing derives its name as a nod to legendary Italian breeder Federico Tesio, whose original property was laced with the sweet fruit. Tesio largely made a name for himself as a genius horse breeder in the early 20th century, later dubbed “the greatest single figure in the history of Italian racing”.

The day-to-day affairs of the Mulberry Racing operation is largely handled by Gregg’s grandson, Lachlan Sheridan. They want to do breeding and racing differently.

“Mike had worked many years in tech and believed there must be a way to use data and technology available to guide our yearling selection process,” Sheridan tells Idol Horse. “We used a proprietary system in our first year and then decided to build our own system: GGX.

“We believe data and technology is the future of every industry – and racing is not dissimilar. We use a data-driven approach in our selection process, and this is complemented by our trainers, utilising gene-testing and form analysis.”

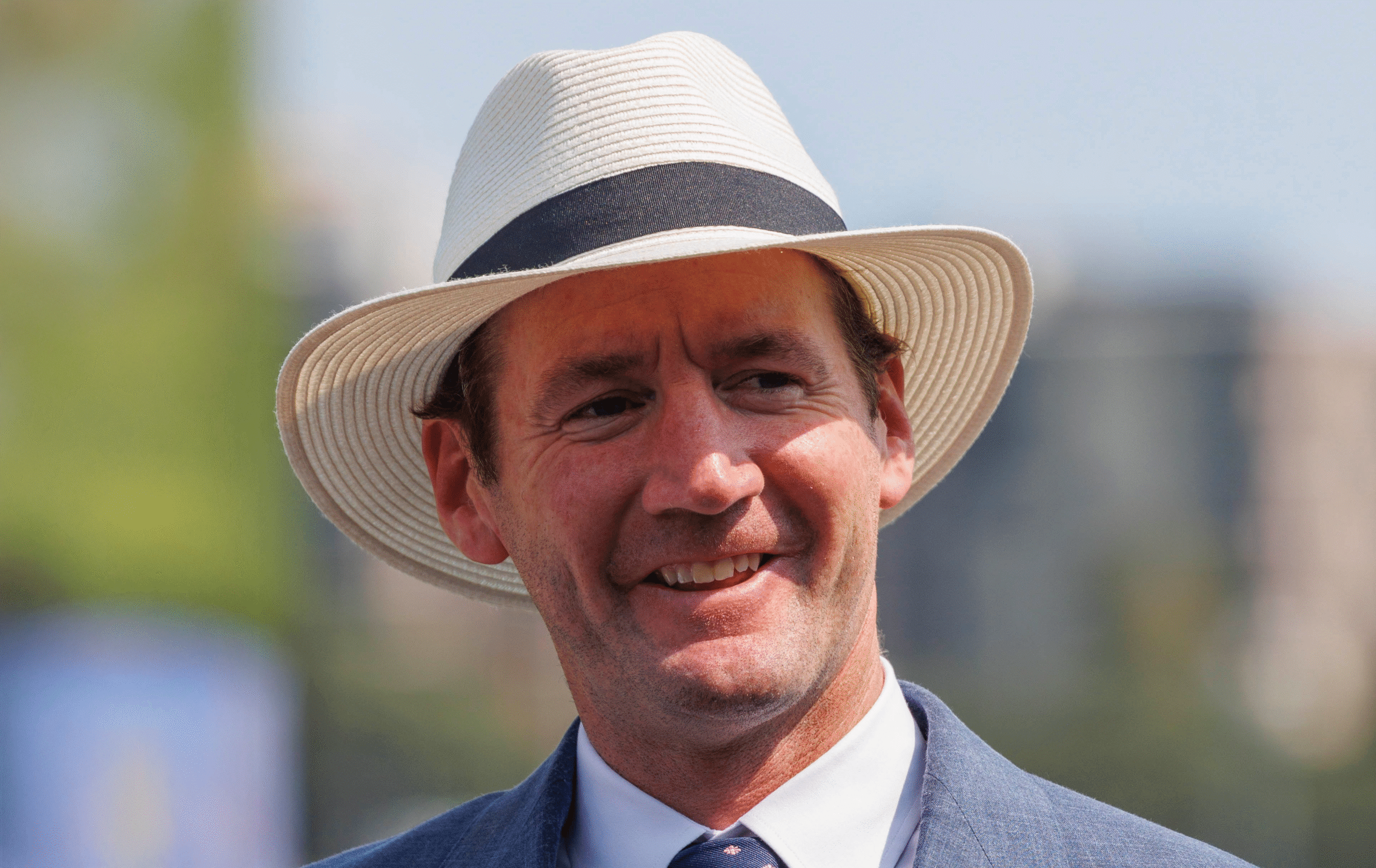

Science and technology is gradually having a greater influence on horse racing and breeding, and perhaps the most innovative trainer in Australia, Ciaron Maher, has admitted he wants to explore how he can potentially use artificial intelligence in the future.

Mulberry Racing is expanding quickly: they have over 40 two-year-olds and yearlings in Australia as well as six in the United States for Brendan Walsh.

“We have always had a strong bond with Brad Widdup Racing and their approach using modern technology, innovative training methods and a patient approach, aligns with Mulberry’s philosophy,” Sheridan says. “It’s also important that for both teams: the horse always comes first.”

It’s unclear exactly how much Mulberry Racing paid for The Everest slot, but Racing NSW charges other investors A$700,000 a year for the privilege of choosing a horse to compete in the A$20 million sprint at Royal Randwick.

It would be fair to assume given the significant demand for the position, Mulberry Racing would have paid more than that. They want to have their own horse capable of competing in The Everest within the next couple of years.

But perhaps its big benefit for the concept is unlocking technology which can help Racing NSW attract a new generation of horse racing enthusiasts. And that has been the whole ethos of The Everest.

“We don’t have much to reveal at this time in terms of promotion, but stay tuned,” Sheridan says. “You’ll see what we have planned later this year.” ∎