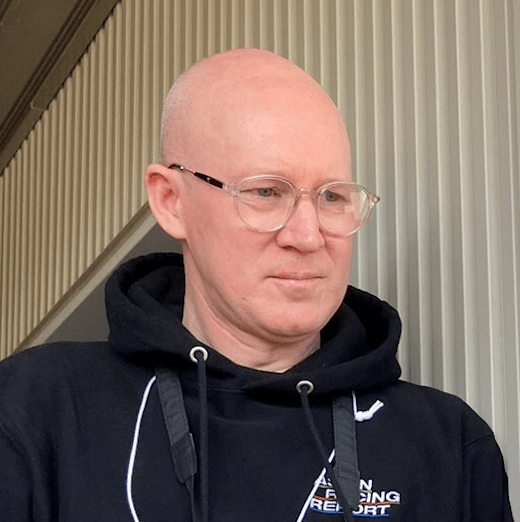

Mirco Demuro’s California Reboot: “People Ask Why I Left Japan”

The Italian’s time at Del Mar this summer has been refreshing despite the tough task of developing support, but whether he will return full-time to Japan is a question that remains open.

“I’M NOT OLD but I’m not young anymore,” says Mirco Demuro.

That statement’s climax carries a stinging reality, one that the Italian is working hard to push against. But perception often has momentum and at 46 he finds himself battling to prove he is not washed up, not yet.

His task does not carry the impossibility of King Canute’s fabled lesson – the futility of commanding the tides of the sea to turn back – but he knows it won’t be easy. Demuro has spent his summer trying to refresh and reset on the Southern California circuit riding out of Del Mar, which last weekend staged its main feature, the G1 Pacific Classic.

The veteran John Velazquez, seven years Demuro’s senior, won that race and followed up with another couple of Grade 1 wins at Saratoga the next day, as if proving Demuro’s initial assertion that he really isn’t old, not in relative terms. But Velazquez is a storied veteran of the North American jockey cohort, a Hall of Famer: he has the reputation, the record, and the support network long since established; those are things Demuro has left behind in Japan – for now, at least – and must build from scratch on America’s west coast.

His move to California came part-way through his 11th season as a fully licensed rider in the Japan Racing Association (JRA), an arena he has excelled in – 1,329 wins including Classics, Japan Cup and Grand Prix features – and may yet return to, but one in which he has been gradually and excruciatingly shunted to the fringes, far from the lustrous centre he once inhabited.

“Japan is the best country in the world, it’s clean, people are so nice, they respect you, everywhere I go they love me, so there’s nothing to complain about, Japan is wonderful,” he says with obvious sincerity, yet the contrasting clause is waiting for its inevitable cue.

“But I love to ride,” he says, “this is my life, I love to ride horses and I needed to change something. I cannot stay home and criticise myself all the time because people weren’t happy about my ride: ‘Oh, you were sitting too far back,’ or ‘You were not good at the start,’ that drove me crazy; ‘You don’t push until the end,’ you know, all this starts to come out and you get tired.”

Perception blurring with reality is how Demuro sees that spiral of decline.

“I tried to come back to the United States three years ago,” he says, “but then I moved from Tokyo to Kansai and my agent said, ‘No, don’t go over to the US because if you go over there you will lose even the small business that you have now.’ He said to me, ‘Things will change if you try harder.’ But I always tried hard and now it’s been six years like this.”

Roll back to the spring of 2015 and Demuro, a multiple champion jockey in Italy, made history alongside Frenchman Christophe Lemaire as the first expatriates to ride as full-time JRA-licensed jockeys – they remain the only two. Demuro’s first four seasons brought tallies of 118, 132, 171 and 153, including 57 Group race wins in that glorious period, 18 of them Group 1s.

Even before his full-time status in Japan was earned, he was at the heart of two of the most iconic moments in Japan’s horse racing history: riding Victoire Pisa to Dubai World Cup victory in the aftermath of the devastating earthquake and tsunami of 2011, and the following year his dismount and kneeling, low bow to the Emperor after Tenno Sho (Autumn) success at Tokyo racecourse during one of his many short-term stints going back to 1999.

But in 2019 Demuro’s tally dipped to 91, with only three Group race wins: his total decreased year on year through the next six campaigns down to the 12 he had for 2025 when he left mid-summer. As young, well-supported Japanese jockeys emerged and other high-profile expats took more rides on Japan’s offshore raiders, Demuro found himself fighting against the tide.

Add to that slide the JRA’s ice cold response to his inquiries about becoming the first expatriate to hold a trainers’ licence – a long-held dream – and Demuro knew he needed to change something.

“I asked the JRA: can I be a trainer here if I start in two, three or four years? And they said, the test will be in Japanese. So how can I make the test in Japanese? I speak Japanese but I cannot write Kanji and those things, so that means I am shut out. I had to think about what I wanted to do,” he says.

“In the last six years I’m down, down, down, so I didn’t accept that situation anymore. It didn’t make sense for me to keep trying in that situation, so I thought, if I have to try, I will try another country.”

He had ridden in California early in his career and recalled the enjoyable time he had there.

“I came here when I was 17 and I was riding for the best trainers here, Bobby Frankel, Richard Mandella … I left my heart here when I was a kid,” he says.

“I like the United States, I love it here so much, so the plan was to come here for three months to see if things change, if I will do good here or if I will do bad here. But things are going ok.”

Much about his future, it seems, depends on how the next few weeks in California pan out. It all started brightly on July 18, a win on Ribbons for trainer Leonard Powell in a maiden special weight, but he always knew it was going to be tough to establish support.

He could have done without the race spill in the G2 Pat O’Brien Stakes in late August that left him “sore” yet thanking God nothing was broken, but that didn’t dampen his enthusiasm to get back out there and keep on proving his worth.

By the end of the Pacific Classic fixture, he had six wins total and three of those had been achieved in the previous nine days. Those wins were not in the Graded race features, though, they came in a couple of maidens and a claimer, carrying win purses of between US$16,000 and $48,000, a far cry from the big money raced for on the JRA.

Still, they took the earnings Demuro’s mounts had accrued this summer through the half-a-million-dollar mark.

“You cannot compare the prize money to Japan,” he says. “The Del Mar Oaks was like $300,000, so it’s like a Group 3 in Japan. But life is not all about money: it’s important because it gives you the best life, but you can have all the money you want and still be unhappy. I’m doing this because I love horses: yes, I want to make money, I want to survive and feed my family, but money is not everything.

“People ask why I left Japan: I left because I didn’t ride much anymore in Japan, I just got tired of trying hard without results.”

Demuro had become jaded both mentally and physically. The California lifestyle has helped him renew: he talks of how close the beaches and the track are to where he is living; barbecues at the homes of horsemen are common and relaxing ways to socialise and connect. But it is the opportunity to ride more horses in the mornings that he is relishing most of all.

“In Japan I was still riding the Derby, the Oaks, big races, even for Northern Farm with a chance, which I very much appreciate,” he says, “but during a normal race day, I was riding two or three races. Not just that, though, on Wednesday morning I’d go to work and ride only one, maybe two horses, so because of this I was struggling to do the weight, because when you train in the gym it’s not like riding a horse.

“Here in California, I’m happy, I’m fit, I (weigh) 115lb and in Japan I could not do 120lb because I didn’t have enough horses to work in the morning to keep the weight down.

“People think that I’m Italian so I need to party, that I need to drink wine, but I don’t really like drinking,” he continues, “I’m a very simple person, I wake up, I go to work, I love my horses, I ride the horses, have a shower, go to the beach, come back, go to the races; then dinner very early, nine o’clock I’m in bed because you have to be up early for work and I’m working almost every day.

“It’s slower on Tuesday so my agent says, ‘You need to rest because you work all week, so rest,’ but I say I don’t need to rest because in Japan I had too much rest. I love to work, I love what I’m doing, I don’t have hobbies, my hobby is riding horses.”

Demuro’s agent is the veteran Tony Matos, agent in the past to stars including Angel Cordero, Laffit Pincay and Gary Stevens.

“I have the best agent in the United States,” he asserts with certainty. “When I call him and he doesn’t answer the phone, you hear the message: ‘This is Tony Matos, agent for Mirco Demuro,’ that makes me so happy. You know, I just arrived here and people remembered me: ‘Hey Mirco, come to my barn, tomorrow you will ride this, you will ride that.’”

The positivity of interactions around the backstretch was enough in itself to refresh Demuro from a situation that has become increasingly awkward in recent years.

“In Japan it’s become like I walk into the stable and I say hello and people look at me like, ‘Oh, we can’t use you anymore because you are old and are not doing good,’” he says. “In Japan they don’t use you because your percentage is bad; but let me ride the good horses! How do you want me to bring the percentage up? It’s impossible without the better horses. You get tired: you try hard but after six years, if you don’t see the result, you get tired of that.”

For all of his frustrations about diminished support, Demuro has not given up on his life in Japan where he has his home. He knows better than most the rewards that come to a jockey there when success is your bedfellow.

“If things go good in Japan, it doesn’t make sense to go anywhere because Japan is the best in the world for horse racing and I have a great love for Japan and the people there, but at the moment I don’t know if I should to go back to Japan (full-time), that’s something I need to work out,” he says.

“I have to go back to make the licence renewal for next year, because you never know. It would be a shame to give up the Japanese licence after I worked so hard for two years to get it and passed the test, but I won 43 Group 1 races and I see jockeys with less ability than me having more chances than I have.”

He says he knows that no one has a right to demand success, but he says, “In Japan I can’t feed my family on 12 winners,” and that reality is at the heart of contemplations about his future.

“My dream is to win a Breeders’ Cup race one day, so I’m working on that, but I don’t know: at the moment I’m open to everything. I don’t want to stress myself, I stressed for six years and criticised myself too much, so for now, for this summer, I want to enjoy life and I’m doing that riding horses every day.”

Whatever the future holds for Demuro, be that back in Japan or pressing on with carving out a foothold in the United States, his spell in Southern California is a timely refresher.

“My wife says, ‘What happened to you? I’ve never seen you like this!’” he adds and laughs, “In America I feel like I’m 10 years younger.” ∎